マネジメント&マ-ケティング

2018年2月 志村英盛

マーケティング戦略の実践

マーケティング戦略とは、顧客が気づいていないニーズやベネフィット

(顧客が満足感を持つ利点)を顧客に気づかせ、さらに新しいベネフィットを

開発し、絶えずプライスベネフィット(価格対満足感比)を向上させること

によって、顧客に新鮮な購入満足感を持ってもらう企業全体の活動である。

別の言い方をすると、需要創造を続けるための組織全体の販売工夫

(はんばいくふう)活動である。小売業界やフードサービス業界で一般的になった

ショツピング・モール全体(例:ラスカ熱海)、商業集積地全体、

地域全体(例:黒川温泉)、あるいは業界全体の需要取り込み活動は、

まさに、マーケティング戦略実践である。

戦国時代、織田信長に仕えたた木下藤吉郎は、武技や格闘能力や学識は

特にすぐれてはいなかったが、高度のマーケティング実践力を身につけていた。

藤吉郎は足軽のときから、主人・信長の刻々変わる二ーズを的確に見ぬき、

タイムリーに問題解決のために自発的に行動し、実績を積み重ねることによって、

異例の大出世をとげた。

信長は、藤吉郎のような足軽に、自分の二ーズを教えることはなかった。

藤吉郎のほうも、信長が教えてくれるとは微塵も期待していなかった。

藤吉郎は常に情報感度を研ぎすまして、信長が直面している状況の変化を

レーダー的情報収集力で的確につかみ、信長の二ーズを見ぬき続けた。

企業経営者は、顧客を信長と考えなければならない。顧客が二ーズを

教えてくれることを期待してはならない。顧客二ーズは、藤吉郎のように、

企業経営者が自力で見ぬかなけばならない。

潜在顧客を発見して、隠れているニーズを見抜くためには、レーダーのように

自分の方から電波を発射して情報を収集しなければならない。

藤吉郎は、蜂須賀小六や、竹中半兵衞や、黒田官兵衞などの

優れたスタッフの知恵をフルに引き出し、把握した信長のニーズを

満足させる様々な創意工夫で信長の信頼を深めていった。

特筆すべきことは、藤吉郎は、これらの優れたスタッフを、権力、武力、

暴力、カネの力で部下にしたのではなく、理念、情報力、判断力、戦略、

方針等で部下にすることができたということである。

これからの時代の企業間競争において勝ちぬけるかどうかは、

企業経営者が、藤吉郎的マーケティング実践力を身につけているか

どうかにかかっている。

予習挑戦型人財が増える

ポジティブな組織風土にしよう

風土とは土壌・地形・気候を全体としてとらえた自然環境のことである。

恵まれた日本の風土と大きく異なり、アフリカやシナイ半島の

砂漠の風土では種をまいても植物は育たない。

企業の組織風土とは、企業において人々が働くための、

組織、ルール、行動慣習、思考様式、価値観、意思決定を

全体としてとらえた企業環境のことである。

日本の経済成長を支えてきた、トヨタ、ホンダ、パナソニック等、

優れた企業のポジティブな組織風土は社会に貢献する人財、

ベネフィットを創り出す人財を数多く育ててきた。

これとは大きく異なり、一攫千金を至上とした米国の投資銀行・

リーマン・ブラザース等のマネー・ゲーム企業の

ネガティブな組織風土は、米国のビジネス・スクールを出た

優秀な経営修士から、実に多数の金融詐欺師たちを生み出し、

社会に大きな惨禍をもたらした。

大金を懐にいれて、金融詐欺師たちはいち早く遁走して姿を眩ました。

しかしながら、金融工学詐欺=金融危機ため、世界各国は

大不況に陥り、大きな経済的ダメージを蒙った。

特に、まじめに働いていた数千万人の労働者に、失業という惨禍を

もたらした。現在に至も、世界各国で多くの人々が、金融工学詐欺に

起因する企業の崩壊、消費沈滞、設備投資不振などによる

経済的惨禍に苦しんでいる。

予習挑戦型マネジャーが特に重要

黒字企業と赤字企業の大きな違いの一つは、予習挑戦型人財が

増えていくポジティブな組織風土であるか、

それとも予習挑戦型人財が減ってしまうネガティブな組織風土で

あるかという組織風土の違いである。

人財が増えるポジティブな組織風土は、

また相互信頼感が強まる組織風土でもある。

ドラッカー教授は『現代の経営』(ダイヤモンド社1996年1月発行、原著は1986年発行)の

『第10章 フォード物語』で、「わずか15年の間に起こった

成功から崩壊に至るフォード物語ほど、劇的なものはない」

「自動車業界では、この15年の間、フォードは一度として

黒字だった年はなかったと広く信じられている(おそらく

間違いではあろうが)」

「その現実はあまりにひどく、再建は難しい、あるいは、

人によっては不可能とまでいうほどだった」

「ヘンリー・フォードの経営の失敗の根本原因は、

10億ドル規模という巨大企業を

マネジャー(=経営管理者)抜きでマネジメントしょうとした

ことにあった」と述べている。

経営者が企業を私物視しているような企業の

ネガティブな組織風土では

有能な予習挑戦型マネジャーは増えない。

ヘンリー・フォードの経営の失敗の根本原因は、

フォードの組織風土を、

予習挑戦型マネジャーが増えないネガティブな組織風土に

してしまった

ことである。

日経ビジネス05年1月3日号第46頁~第47頁は

『中間層なき悲劇 西武凋落は人材育成を怠ったツケ』

という見出しで、

「会社を支えるミドル(中間層)が機能せず、

現場の活力が失われていく」

「ミドル不在の断層が拡大して組織は機能不全に陥った。

西武グループの悲劇は、

強すぎるカリスマと弱すぎるマネジメント層から成る

前近代的組織が生んだ悲劇だ」と述べている。

ドラッカー教授がフォード物語で取り上げた経営失敗事例の

典型的な日本版が西武グループである。

日経産業新聞05年2月24日第3面は1兆4000億円にも上る

グループ有利子負債を生んだ元凶とされるホテル・リゾート事業は、

食器一つに至るまですべて堤義明氏の一存で決められてきた。

「ホテル・リゾートは前会長のロマンを形にした事業だったが、

もっと採算を考えてほしかった」

「堤義明氏は、自分はグループの管理者ではなく、

所有者であると勘違いした裸の王様」と報じている。

読売新聞(朝刊)05年2月24日第39面は

「全国でホテルやスキー場、ゴルフ場などの観光施設を経営する

堤義明氏のコクドは、

バブル経済の崩壊で経営が悪化、1996年から昨年まで、

毎年の赤字額は約93億円-約25億円に上った」と報じている。

堤義明氏は巨大な西武グループの組織風土を、

予習挑戦型人財が増えない

ネガティブな組織風土にしてしまった。

明晰な頭脳、強い意志、迅速な行動力を身に付けていた

堤義明氏の失敗は

『現代の経営』でドラッカー教授が指摘した

自動車王ヘンリー・フォードの失敗と完全に同じである。

別の視点から見た前近代的な

ネガティブな組織風土の大きな問題点は、

組織内における情報交流密度が著しく低い

(情報量自体が極めて少ない上に、

情報交流がほとんど無い)ことと、

組織内におけける分業・分担の改善が

ほとんどないということである。

その典型的な実例が、旧大日本帝国の旧陸軍と旧海軍である。

敗戦前の旧陸軍・旧海軍においては、新兵に対する私的リンチが

毎日毎晩行われていた。

しかし、なんらの私的リンチ禁止策は行われ

なかった。

特攻に代表される、参謀と称する高級将校の

作戦判断・指揮はデタラメを極め、

人命尊重意識はひとかけらもなかった。

敗戦前、

名参謀と詐称された陸軍参謀・辻政信はその典型であった。

旧陸海軍の、無知・無能・無策・無責任な最高指導者たちと

高級参謀たちが行った15年間(1931年-1945年)の

昭和戦争の惨禍を体験している者は、

ネガティブな組織風土の恐ろしさを忘れることができない。

最近、問題になっている過労死も、組織内における

分業・分担の改善がほとんどないことが根因である。

つまり、言い換えるならば、

予習挑戦型マネジャーが不在か、

あるいは、表面的には存在する組織のマネジャーが、

無知・無能・無策・無責任で、

組織のメンバー間の分業・分担が

惰性的な成り行き任せで行われており、

改善がないことが根因である。

11年3月11日午後2時46分、突如、東北地方太平洋岸全域を襲った

マグニチュード9.3の巨大地震と巨大津波、それに付随して起こった

福島第1原発の大事故は、日本経済に、永く続く、深い傷を負わせた。

企業経営にとって、今後、従来の発想、判断基準、ノウハウ、システム等が

通用しなくなる事態が数多く生じる。

正確な情報を収集する重要性がさらに高まる。

関連サイト:巨大津波・原発大事故20110311

企業も、個人も、

黒字経営を実践していくことは容易なことではない。

まず何よりも、

情報感覚を鋭くしてレーダー的情報収集力を強化することが

第1である。

迅速・正確な月次決算によって、企業経営者は、、毎月の企業実態を

的確に把握することが必要である。個人でいうならば、自分自身の

健康状態の的確な把握が必要ということである。

毎月、固定費生産性と労働分配率を的確に把握すると共に、

経費の徹底的見直し、経費の徹底的節減が欠かせない。

企業経営者は、信用差額と経常収支を毎月点検して資金体質を

改善しなければならない。

月次決算を迅速・正確にできない企業が生き残ることは難しい。

企業経営者は、これらの数字を正確に把握した上で、1か月先、3ヶ月先、

半年先の資金繰りについてシミュレーションを繰り返し行うことが

必要である。資金繰り予算を絶えずチェックするということである。

企業経営者は、数字を把握したうえで、企業の現状を文書に記述して、

企業実態把握に誤りはないかを冷静に考えなければならない。

これは、たとえていうならば、遠洋航海において、絶えず天体観測を行い、

自分の船の現在位置を確認し、航海日誌に記録しながら航行する

ということである。

企業経営者の【ひとりよがりの思い込み】によって判断を誤ってはならない。

第2は、マーケティング戦略の実践である。

マーケティング戦略とは、顧客が気づいていないニーズやベネフィット

(顧客が満足感を持つ利点)を顧客に気づかせ、さらに新しいベネフィットを

開発し、絶えずプライスベネフィット(価格対満足感比)を向上させること

によって、顧客に新鮮な購入満足感を持ってもらう企業全体の活動である。

戦国時代、織田信長に仕えたた木下藤吉郎は、武技や格闘能力や学識は

特にすぐれてはいなかったが、高度のマーケティング実践力を身につけていた。

藤吉郎は足軽のときから、主人・信長の刻々変わる二ーズを的確に見ぬき、

タイムリーに問題解決のために自発的に行動し、実績を積み重ねることによって、

異例の大出世をとげた。

信長は、藤吉郎のような足軽に、自分の二ーズを教えることはなかった。

藤吉郎のほうも、信長が教えてくれるとは微塵も期待していなかった。

藤吉郎は常に情報感度を研ぎすまして、信長が直面している状況の変化を

レーダー的情報収集力で的確につかみ、信長の二ーズを見ぬき続けた。

企業経営者は、顧客を信長と考えなければならない。顧客が二ーズを

教えてくれることを期待してはならない。顧客二ーズは、藤吉郎のように、

企業経営者が自力で見ぬかなけばならない。

潜在顧客を発見して、隠れているニーズを見抜くためには、レーダーのように

自分の方から電波を発射して情報を収集しなければならない。

藤吉郎は、蜂須賀小六や、竹中半兵衞や、黒田官兵衞などの

優れたスタッフの知恵をフルに引き出し、把握した信長のニーズを

満足させる様々な創意工夫で信長の信頼を深めていった。

特筆すべきことは、藤吉郎は、これらの優れたスタッフを、権力、武力、

暴力、カネの力で部下にしたのではなく、理念、情報力、判断力、戦略、

方針等で部下にすることができたということである。

これからの時代の企業間競争において勝ちぬけるかどうかは、

企業経営者が、藤吉郎的マーケティング実践力を身につけているか

どうかにかかっている。

企業経営者が3番目になすべき事は、マネジメント・イノベーションに

よって企業の組織風土をよりポジテイブ変えていくことである。

風土とは土壌・地形・気候を全体としてとらえた自然環境のことである。

恵まれた日本の風土と大きく異なり、アフリカやシナイ半島の砂漠の風土では

種をまいても植物は育たない。

企業の組織風土とは、企業において人々が働くための、組織、ルール、

行動慣習、思考様式、価値観、意思決定を全体としてとらえた企業環境の

ことである。

マネジメント・イノベーションとは、経営環境変化への適応が遅れて、

慢性赤字状態に陥った企業のネガティブな組織風土を、経営環境変化に

適応できるように革新することである。企業と、そこで働く人たちの、

視野を広げ、視点や意識を変え、仕事の目的、仕事の仕組み、仕事の

プロセス、仕事のやり方を、経営環境変化に適応できるように変えていく

ことである。

そのためには、企業経営者は、先ず、企業の組織風土の実態を、さまざまな

視点で調べ、ポジティブか、ネガティブか、現状認識しなければならない。

調べた実態を文書にしてマネージャーたちと共通認識することが必要である。

日本の経済成長を支えてきたトヨタ、松下、ホンダ等の企業の

ポジティブな組織風土は、社会に貢献する人財を数多く育ててきた。

これらの企業においては、「感謝貢献-努力達成-成長進化」の経営理念が

定着して、日々実践されている。

これとは大きく異なり、一攫千金を至上とした米国の投資銀行・

リーマン・ブラザース等のマネー・ゲーム企業のネガティブな組織風土は

米国のビジネス・スクールを出た優秀な経営修士から、実に多数の

金融詐欺師を生み出した。社会に大きな惨禍をもたらした。

マネー・ゲーム企業は害虫・害獣集団であった。

第4は、変化する顧客ニーズに適応できる貢献意識の高い

予習挑戦型プロ人財の確保、特に予習挑戦型プロ・マネジャーの確保

である。黒字企業と赤字企業の大きな違いの一つは、予習挑戦型人財が

多数派であるか否かである。

予習挑戦型とは織田信長や藤吉郎時代の秀吉のように、絶えず自発的に

情報収集に努め、情報に基づいて状況変化に果敢に挑戦して、革新・改革・

創造に挑むタイプである。徳川家康は本能寺の変の「九死に一生を得た」

体験で、レーダー的情報収集の重要さを身に沁みて認識し、信長や秀吉を

超える予習挑戦型に脱皮した。

予習挑戦型に対比されるのが、復唱前例型と漫然先送り型である。

復唱前例型は指示されたことや前例を忠実に守り実行するタイプである。

指示待ち型と言い換えてもよいと思う。真面目で勤勉であるがレーダー的

情報収集力が弱く、変化に対応する迅速な行動力が弱い。

漫然先送り型は、毎日、漫然と、与えられた仕事を行って、問題はすべて

先送りして、状況の変化に対応する革新とか改革とか創造とかを考えない

タイプである。

豊臣秀吉と石田三成の死後、徳川家康の豊臣家に対するあからさまな

挑発行為に対して、深刻な危機感を持たないまま、新情報源の開拓も、

レーダー的情報収集力の強化も行わず、洞察力と創意工夫皆無で、

生き残るための、なんらの有効な手を打たず、なすことなく滅び去った

淀どの秀頼母子のように、環境の変化に対する危機感が弱い

アスタマニャーナ型とも言える。

これまで27の企業を赤字企業から黒字企業に転換させ、かつ、

黒字転換後も着実に企業成長させている日本電産の永守重信社長は、

復唱前例型人材や漫然先送り型人材を予習挑戦型人財に変える名人だと

思う。

復唱前例型と漫然先送り型が多数派である企業は、これからの時代、

生き残ることは難しいと思う。

入省庁時の資格で組織内での待遇が辞める時まで続く官公庁の

キャリア制度や、旧態依然の大企業の人事制度は、ノン・キャリアや高卒に

とっては、「努力しても報われない」制度である。極論すれば「人財殺し制度」

とすらいえる。抜本的制度改革が必要である。

正社員を極力減らし、ひたすら労働搾取型企業を志向している米国型・

中国型の企業には未来はない。

経営とは、企業規模・体質を自覚した上で、つまり、己を知った上で、

状況に応じて、つまり、状況・顧客・ライバルの動きを把握した上で、

多くの要素を組み合わせて戦略を練り、タイミングよく実行することだから、

企業経営者は、絶えず視野を広げ、視点・立場を変えて観察するとことを

怠ってはならない。

同時に、マネジャーにも同様の努力を求め続けなければならない。

第5は、社員の作文能力向上を軸とする情報化推進である。

IT化推進だけが情報化ではない。顧客ニーズにより良く適応するため、

社員の知恵と工夫を絞り出していく体制の強化こそが必要な情報化である。

社員の知恵と工夫を絞り出していくためには、社員一人ひとりの作文能力を

高めていくことが必要である。

第6は、資金調達による財務体質強化と設備更新等の先行投資である。

企業経営者は、絶えず、視野を広げ、視点を変えて観察し、立場を変えて

考えてみて、顧客ニーズの変化と分業構造の変化を見誤ってはならない。

景気後退や失業増大のみならず、消費の成熟化・多様化、情報化、

グローバル化、高齢化、車社会化、女性の社会進出の一般化、

結婚観・子供観の大変化、未婚率の大幅上昇、離婚率の上昇、

少子化、単身あるい二人世帯の増加、外国人の増加、低所得層の増加

などに伴って、顧客構成や個人ニーズが変わりつつある。

企業経営者は、絶えず資金、人財、時間、設備、立地などの経営資源の

最適配分を研究して、経営資源を競争力の強化に重点配分しなければ

ならない。企業経営者が環境変化に適応できなければ、

企業は廃業、倒産を余儀なくされる。

Company Philosophy:

The Way We Do Things around Here

The Will to Manage

I have an abstract painting in my office that I bought

in London off the Piccadilly fence. In that open-air mart,

which operates on weekends, the artists sell their own works.

Judged by the $43 price, my painting is not great art.

But it has delightful swirls, angles, and other abstract

forms, all in bright colors. And when Mr. Eves, the artist,

told me the title - "Forces at Work" - I bought it immediately.

With a little metal plate bearing the title and the artist's

name, the painting is a constant reminder to me that any

successful organization must give continuing attention

to keeping adjusted to the forces affecting it - that is,

to the forces-at-work element of its philosophy. But before

discussing that element, let us examine the whole concept of

company philosophy as a system component and identify other

important elements of a successful philosophy.

Meaning and Elements of Company Philosophy

Over the years, I have noticed that some executives -

particularly top-management executives in the most successful

companies - frequently refer to "our philosophy." They may speak

of something that "our philosophy calls for," or of some action

taken in the business that is "not in accordance with our

philosophy." In mentioning "our philosophy," they assume that

everyone knows what "our philosophy" is.

As the term is most commonly used, it seems to stand for

the basic beliefs that people in the business are expected

to hold and be guided by - informal, unwritten guidelines'

on how people should perform and conduct themselves. Once such

a philosophy crystallizes, it becomes a powerful force indeed.

When one person tells another, "That's not the way we do things

around here," the advice had better be heeded. And when

a superior says that to a subordinate, it had better be taken

as an order.

In dealing with the concept as I find it used in practice

by leading executives, the literature on company philosophy is

neither very extensive nor very satisfactory. But one dictionary

definition of philosophy does apply: "general laws that furnish

the rational explanation of anything." In this sense, a company

philosophy evolves as a set of laws or guidelines that gradually

become established, through trial and error or through

leadership, as expected patterns of behavior.

In discussing the philosophy of International Business

Machines Corporation, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., the chairman,

says:

I firmly believe that any organization, in order to survive

and achieve success, must have a sound set of beliefs

on which it premises all its policies and actions.

Next, I believe that the most important single factor in

corporate success is faithful adherence to those beliefs... .

In other words, the basic philosophy, spirit and drive of an

organization have far more to do with its relative achievements

than do technological or economic resources, organizational

structure, innovation and timing. All these things weigh heavily

on success. But they are, I think, transcended by how strongly

the people in the organization believe in its basic precepts and

how faithfully they carry them out.'

Some typical examples of basic beliefs that serve as guidelines

to action will clarify the concept. Although such basic beliefs

inevitably vary from company to company, here are five that I find

recurring frequently in the most successful corporations:

1. Maintenance of high ethical standards in external and

internal relationships is essential to maximum success.

2. Decisions should be based on facts, objectively considered

- that I call the fact-founded, thought-through approach to

decision making.

3. The business should be kept in adjustment with the forces

at work in its environment.

4. People should be judged on the basis of their performance,

not on nationality, personality, education, or personal traits

and skills.

5. The business should be administered with a sense of com-

petitive urgency.

These five common-denominator elements - combined with

other beliefs - are informal supplements to the more formal

processes of management. A brief discussion of each will show

how useful and how powerful a company philosophy can be,

once it provides effective guidelines for "the way we do things

around here."

High Ethical Standards

In dealing with the value of high ethical standards in a

business, I don't want to belabor the obvious. But I do want to

point up a few nuances that sometimes escape even executives

of high principle.

Since the whole purpose of a system of management is to

inspire and require people to carry out company strategy by

following policies, procedures, and programs, no management

should overlook the set of built-in guidelines that every employee

with a good family background brings to the job. Since anyone

who has been well trained in Judaic-Christian ethics instinctively

acts in accordance with those principles, it is sheer

shortsightedness for any management to overlook the great practical

value of these powerful guidelines of conduct.

The business with high ethical standards has three primary

advantages over competitors whose standards are lower:

①

A business of high principle generates greater drive and

effectiveness because people know that they can do the right

thing decisively and with confidence. When there is any doubt

about what action to take, they can rely on the guidance of

ethical principles. I can think of three companies - the leaders

in their respective industries - whose inner administrative drive

emanates largely from the fact that everyone feels confident that

he can safely do the right thing immediately. And he also knows

that any action which is even slightly unprincipled will be

generally condemned.

②

A business of high principle attracts high-caliber people

more easily, thereby gaining a basic competitive and profit

edge. A high-caliber person, because he prefers to associate with

people he can trust, favors the business of principle; and he

avoids the employer whose practices are questionable. So, in taking

his first job or in changing jobs, he takes the trouble to find out.

For this reason, companies that do not adhere to high ethical

standards must actually maintain a higher level of compensation

to attract and hold people of ability. A few large companies have

to "reach" for able people with higher compensation simply

because low standards of relationships among people produce

a "jungle" atmosphere in which it is less agreeable to work.

③

A business of high principle develops better and more profitable

relations with customers, competitors, and the general public,

because it can be counted on to do the right thing at all times.

By the consistently ethical character of its actions, it builds

a favorable image. In choosing among suppliers, customers resolve

their doubts in favor of such a company. Competitors are

less likely to comment unfavorably on it. And the general public

is more likely to be open-minded toward its actions and receptive

to its advertising and other communications.

Consider the example of Avon Products, Inc., the house-to-house

cosmetics business. Since 1954 Avon's net profit has been

increasing at an average of over 19 percent a year, compounded,

and in 1963 its return on investment reached 34 percent. According

to an article in the December 1964 issue of Fortune, Avon's founder,

David H. McConnell, "was resolved to be different from the swarms

of itinerant peddlers who were at that time selling goods of

indifferent quality to housewives, and then moving on, rarely

to be seen again." The founder's son carried on his father's belief

in high principle. Citing comments by competitors and suppliers

on the company's high ethical standards, the article notes that

Avon's present chairman, John A.Ewald, its president, Wayne Hicklin,

and a top-management executive now deceased "did a great deal

to ensure that the McConnells' high ethical standards would

continue to be diffused throughout the organization as it expanded."

There should be no need to dwell on these well-recognized

values. But too often, I find, they tend to be taken for granted.

My point in mentioning them is to urge executives to actively

seek ways of making high principle a more explicit element in

their company philosophy. No one likes to declaim about his

honesty and trustworthiness; but the leaders of a company can

profitably articulate, within the organization, their determination

that everyone shall adhere to high standards of ethics. That is

the best foundation for a profit-making company philosophy and

a profitable system of management.

The End

Sense of Competitive Urgency and

Developing a Company Philosophy

The Will to Manage

Sense of Competitive Urgency

Based on my own comparisons of the administration of leading

American and British companies, I believe that the greater

management effectiveness achieved by leading American companies

is due chiefly to the greater sense of competitive urgency

that pervades our most successful businesses. Addressing

the Industrial Copartnership Association in London, in 1961, H.R.H.

The Duke of Edinburgh put it this way: "Foreign competition is real;

it is going to get tougher, so that if we want to be prosperous

we have simply got to get down to it and work for it.

The rest of the world most certainly does not owe us a living."

Certainly management technique is less important than

competitive urgency. Even the most advanced management methods

will not be fully effective unless these techniques are adopted

and administered with a sense of competitive urgency.

Talking to an international management congress,

the late Charles E. Wilson, then president of GM, put it this way:

Too frequently visitors to America are overly impressed by

our assembly lines and our progressive mass-production

manufacturing methods and are inclined to think that the physical

organization of the work is the essence of our American production

system. They will be confusing the form with the substance

if they believe that simply by installing assembly lines

and progressive manufacturing they will automatically get the

same efficient production and low cost that American industry

achieves. If they do not understand and apply the other

fundamentals of our system at the same time, they will be

greatly disappointed with the results they get... .

The first essential of our American industrial system is

the acceptance by Americans of competition. The responsibility

for individual competition as well as competition between

companies and business organizations stimulates the millions of

Americans to contribute to better ways of doing things and to

accomplish more with the same amount of human effort.*

What can the leaders of a business do to develop a sense of

competitive urgency? In addition to their alertness to external

forces at work, here are the chief characteristics of competitive

top-management executives as I have observed them in action:

1.

The competitive executive gets on with it. He treats time

as his most valuable commodity and paces himself accordingly.

He does not "fiddle around." At the same time, he works with

calm purposefulness, rather than frantic haste.

2.

The competitive executive works with zest. Typically, he works

harder and more effectively than his subordinates. He sets

a good example in work habits, not for the sake of setting

an example but because he has a real zest for his job.

3.

The competitive executive is decisive. After getting the facts

and thinking the problem or decision through, he makes

a considered decision. He recognizes that he will make mistakes,

but he knows that his competitors will, too; and he prefers risk

of error to unnecessary delay. He knows he can safely be wrong

part of the time, provided he keeps alert to opportunities

for correcting errors.

I recall an executive who habitually made instant decisions

that were not always sound. In talking with him, I discovered

that just after graduating from college, he had spent a year

as a minor-league baseball umpire. So he fell into the habit of

making business decisions with nearly the same speed.

Once aware of this, he realized that an executive - unlike

an umpire - has an opportunity to gather and consider facts,

to change his mind, and to correct his mistakes. So he began

taking a little longer to think decisions through - and raised

his batting average considerably.

4.

The competitive executive seizes and exploits opportunities.

He is more interested in building on strength than in shoring

up weaknesses. He devotes more time to building his own

company's position than to countering competitive moves.

Therefore, a system for managing appeals to him.

5.

The competitive executive seeks out and faces up to problems.

He knows that the passage of time usually makes a tough

problem even harder to solve. But when it cannot be solved

immediately, he turns to developing company strengths and works

around the problem while waiting for a better time to solve it.

6.

The competitive executive does not shrink from difficult

personnel decisions. He knows that unless poor performance can

be overcome (as it often can), it is fairer to the company and

the individual to remove him sooner rather than later.

But the competitive executive is fair and not ruthless.

He knows a management system will not be effective unless

it facilitates fair and sound decisions affecting people.

Fair decisions concerning people are often received

surprisingly well even by the person who is adversely affected.

I recall the case of the leading salesman of a large industrial

products company who spent much of his time at race tracks.

Because of the large orders the marketing director thought

the salesman controlled, for many years no action was taken

to replace him. When a new marketing executive finally dismissed

him, the salesman said he wondered why the action had not been

taken long before. Of course, customer respect for the company

increased, and no orders were lost.

7.

The competitive executive focuses on increasing the company's

share-of-market at a profit. His every action is directed

toward building a stronger competitive position for the long term;

but he takes the action now.

These are some of the characteristics of the executive who

possesses a sense of competitive urgency. This incessant drive

"to get on with it now" is necessary to succeed in our competitive

profit-and-loss economy. More than management techniques,

it makes our system the best means yet discovered for fulfilling

people's material wants and needs profitably and for providing

the psychic benefits of work itself. But that drive can be made

more purposeful and effective by a management system. In turn,

a management system helps develop a sense of competitive urgency.

The interaction increases the likelihood of success for any enterprise.

Developing a Company Philosophy

In discussing the need for developing a company philosophy,

rather than just letting it happen, I have selected from successful

company experience just five common elements that make a good

philosophical foundation for any business. To them, the management

of any company or division can add other beliefs that should guide

the organization. If they are to be a real part of the philosophy,

however, these beliefs should be basic enough to become overriding

guidelines to action.

Even without planning or specific effort, any company will gradually

develop a philosophy as people observe and learn through trial and

error "the way we do things around here." However, it is my conviction

that a positive program by top management to build or reshape a sound

fundamental philosophy should be the underlying and overriding

component of the company's system of management.

Whatever beliefs top management wants to build into its philosophy

must, of course, be demonstrated in practice if they are to take firm

root in the minds of people throughout the organization. But to make

the guidelines really operative, something more is needed than

the power of example. Executives and supervisors at all levels

should articulate the company philosophy, relate it to actual situations

and problems at hand, and point out to subordinates where their actions

square, or fail to square, with the beliefs of the organization.

It is through this kind of leadership that a company philosophy

for success can be most soundly and securely built.

Deeply and widely held beliefs in "the way we do things around here"

provide a solid foundation on which to erect a programmed management

system. And these beliefs interact with other system components

to give them strength and to gain strength from them. This is especially

true of the next component I discuss: strategic planning.

The End

Re:

日本航空(JAL)のV字回復

-日本航空だって出来た-日本経済は必ず再生する!

資料出所:読売新聞(朝刊)10年1月21日第1面

自由に発言できるポジティブな組織風土をつくれ

会議で積極的に発言したり、積極的に上司に意見具申すると、

「上司をないがしろにしている」、「生意気だ」、「常識がない」、

「チームワークを乱す」、「立場の違いが判っていない」、

「ひとの領分に口出しするな」、「自分の分をわきまえていない」

「事前に根回ししたこと以外の問題を持ち出すな」

などと非難されたり、悪口を言われ、結局、仲間はずれにされたり、

左遷されたり、冷遇されるのが、予習挑戦型マネジャーが減ってしまう

ネガティブな組織風土である。

企業や経営者や上司に対する愛社精神・忠誠心と、会議において

経営者や上司の、現状認識・事実認識・方針・戦略について、

自由に率直に意見を述べることとは別のことである。

太平洋戦争敗戦以前の日本の「タテ社会」構造での思考様式や、

長い時間をかけて培われてきた日本的儒教や武士道の、

「主君に対する忠誠心最重視意識」が、

「会議での積極的な発言を経営者や上司に対する反逆視」する遠因

になっているが、

「自由・率直な意見表明を封じる」、

特に「経営者や上司の考え方についての意見表明を封じる」ことが、

逆に、企業や経営者やマネジャーをダメにしてしまうことを、

経営者は十分に理解しなければならない。もちろん

「会議での積極的な発言を経営者や上司に対する反逆視」する

ネガティブな組織風土では予習挑戦型マネジャーは増えない。

経営環境の複雑な変化の重なり合いが、時々刻々と起きている

時代にあっては、

【自分の目や考えに狂いはないという思い込み】

【情報に基づかない思い込み】

【狭い視野での情報】

【偏った視点からの情報】

【単細胞的な短絡的な考え方】

【前近代的な価値観】【身分意識や先輩意識や個人感情にこだわった意見】

などは、経営者の的確な現状認識や意思決定の妨げとなることを、

経営者は十分に理解しなければならない。

日本経済新聞(朝刊)2008年11月5日第40面【私の履歴書】で

松田昌士(まつだまさたけ)JR東日本相談役は

「国鉄組織はそれぞれの専門分野に合わせて、縦系統の統治を伝統としていた。

機械系、土木系、そして事務系の3系統である。

弊害は言わずと知れた過剰な縦割り意識を生み出すことである。

結局、どの系統も、了見の狭いムラ意識に凝り固まり、広く遠い目で

【国鉄のため】と考えることができなくなる。

国鉄が駄目になった理由の一つは、

風通しのよい組織風土が育たなかったこともあると思う」と述べている。

読売新聞(朝刊)2006年3月2日第8面で日本航空の外部諮問機関

【安全アドバイザリーグループ】の座長を務める作家・柳田邦男氏は

「(日本航空は)これまで【声を上げれば唇寒し】の社風だったが、今回、

管理職が署名運動を展開するなど、経営のあり方に発言するようになったのは、

風通しが良くなる前兆といえる」と語っている。第2面で、社長に就任する

西松遥氏は【社内でものが言えるような風土にしたい】と語っている。

今までは【ものが言えないネガティブな組織風土】であったわけだ。

日本には、日本経済を支えている、トヨタ、松下、ホンダ、シャープなど

優れた企業が数多くある。これらの企業においては、社内に相互信頼感が

定着しており人財が増えるポジティブな組織風土がある。

日本航空は経営者たちのみならず、マネジャーたちも、

労働組合の指導者たちも、

頑なに既得利権を固守するという狭い視野から抜け出し、

視野を広げ、視点を変えたものの見方考え方を取り入れて、

虚心坦懐に日本経済を支えている優れた諸企業の

人財が増えるポジティブな組織風土を見習って、

まず、相互信頼感が強まる組織風土づくりに

真剣に取り組まなければならないと思う。

社内において相互信頼感が欠けているのに、

顧客に【日本航空を信頼して下さい】と言えるのだろうか?

読売新聞(朝刊)2006年3月3日第3面の【社説】『日航再出発-危機感

共有し輝きを取り戻せ』は「相次ぐ運航トラブルで元々揺らいでいた

日航への信頼感は、内紛によってさらに低下した。客離れは深刻だ」と

論じている。筆者は、この点について、日本航空の九つの労働組合の指導者

たちは真剣に反省する必要があると思う。

The Resolution to achieve

from the book written by Kazuo Inamori

The Purpose of Business

One year after I founded Kyocera, I realized that I had started

something outrageous.

Eight of us started the company to prove that the technology

we developed could be accepted by society.

But before long, several young people we had hired demanded

that we guarantee their future income!

I had to seriously ponder the question, "What is an enterprise?"

I was in no position to guarantee anybody's future livelihood,

not even my own family's.

Still, these employees were entrusting their future to our company.

There was no way that we could betray the expectations of

our employees, who were basing their lives on their jobs with us.

Three days and nights of impassioned discussions made me change

Kyocera's corporate mission.

We shifted our priority from technology to employees.

Kyocera's management rationale is to provide opportunities

for the material and intellectual growth of all our employees, and,

through our joint effort, contribute to the advancement of society

and mankind.

Our business shall strive first to provide opportunities

for our employees. Building upon this, we shall jointly contribute to

the progress of technology, society, and humankind.

I believe these are the only worthwhile objectives of our business.

Make Customers Happy

It's a cliche to say that the way to a profitable business is to

"make customers happy."

Still, some companies misunderstand the real meaning of "profit"

and run their business solely for their own benefit.

Such an attitude should never exist.

The principle of business is to please people.

We must certainly make our outside customers happy.

And we must please our internal customers, too - the other employees

and departments who depend on us.

The reason we work hard to meet a deadline is to deliver our products

when our customers need them. We make state-of-the-art products

to meet and exceed our customers' expectations.

We continually develop new products to help our customers

make more profit themselves.

Everything we do in business derives from our principle of pleasing

our customers.

Too many people think only of their own profit. But business opportunity

seldom knocks on the door of self-centered people. No customer ever

goes to a store merely to please the storekeeper.

Persons who can successfully manage a great business are

those who can make their customers more profitable.

This attitude will invite more business opportunities and bring profit

to their own company.

The Essence of Business

As society develops, age-old truths get lost among complex circumstances.

In managing a business, we should never forget what the essence of

our business is.

Right before the first OPEC oil crisis, a land boom started inJapan.

Many companies vied with one another to purchase land, expecting prices

to skyrocket. Our banker, in fact, came to plead with us. He said he was

delighted that we were depositing our profits with him - yet as our banker,

he felt compelled to advise us that we could be making a fortune by investing

in real estate!

I politely replied that our business was to make profit in the traditional way

by manufacturing products and adding value, not by speculating on land prices.

Then the old crisis came, and most companies had their money tied up in land.

Kyocera, however, was able to use its liquid assets to invest in plants and

equipment. I was praised for our excellent balance sheets and my "clairvoyance."

Of course, no one can foresee the future. But while others looked

at the facade, I held on to basic truths and principles and adhered

to what I believed was the essence of our business.

Follow Profit & Loss Daily

You cannot successfully manage a business like a guru(religious leader)

in seclusion, looking down on others at a gret distance and occasionally

bestowing a few words of wisdom. Instead, think of it as a slow

accumulation of daily routine activities.

Managing a business, whether it is a large corporation or a small shop,

is a daily accumulation of numbers. We can't manage without analyzing

expenses and sales on a regular basis.

But looking at a monthly income statement to run your business is still

not enough. Your monthly profit is based on the daily accumulation of

operational results.

Therefore, you must behave as if your profit and loss statement is being

produced every day, and manage your operation accordingly.

Operating our business without paying attention to the daily figures

would be like flying an airplane without looking at theinstrument panel.

We would lose track of where we were flying and where we were

supposed to land. The same can be said of operating a business.

If we don't keep an eye on daily business operations,

we will never reach our goal.

An income statement is a portrait of how the manager has behaved daily.

Passion Leads to Success

When I evaluate anyone, I consider that person's talent and ability.

But I believe it is equally important to consider the passion that person

possesses.

That's because if you have passion, you can accomplish almost anything.

If you don't have ability, but have passion, you can arrange to have

capable people around you. Even if you don't have funds or facilities,

people will respond to your dreams if you allow your passion to persuade

them.

Your passion is the source of success and accomplishment;

the stronger your will, enthusiasm, and passion for success, the

better your chance to succeed.

Passion is a state in which you think of something 24 hours a day,

even as you sleep.

In reality, it is impossible to keep thinking consciously 24 hours a day.

However, it is important to maintain such an intention.

In so doing, your desire will reach your subconscious mind - which can

indeed remain focused asleep or awake.

The key to success is your passion.

The Drama Called "Enterprise"

I regard a company as a theatrical troupe of sorts which performs a drama

called "Enterprise."

Many different roles are needed to stage a drama.

A famous actor and actress may play starring roles.

And there are protagonists, heroes, villains, and enemies.

The backstage crew, musicians, and electricians all work together

to produce the play.

All human beings are equal;

these actors merely have different roles.

If the stars wore stagehands' work clothes, the drama probably

wouldn't make sense. Actors and actresses have to dress and

act their part.

And, so it is with a company. Being the president is just a role.

If the chief executive officer is shabbily dressed, the company's

image may suffer.

Officers also receive certain privileges that are commensurate

with their responsibilities, because it is their role.

However, this does not permit them to be opportunistic or take

advantage of others - that would constitute an abuse of authority.

The quality of a company reflects the passion for excellence that

each member of the cast displays.

While the roles may differ, each actor or actress is a professional

in his or her own right.

Passion with a Pure Mind

True passion can bring you success.

But if the passion arises from your own greed or self-interest,

the success will be short-lived.

If you become insensitive to what is right for society, and start

pushing ahead thinking only about yourself, the same passion

which brought you success initially will cause you to fail in the end.

Ultimately, success depends on the purity of the desire that reaches

our subconscious minds.

It would be ideal if we could rid ourselves of our selfishness and

have completely altruistic and pure desires for humanity and society.

But it is almost impossible for us, as human beings,to fully eradicate

our self-interest and greed. And we should not feel ashamed of this.

We need some egotistic desires as part of the self-preservation

mechanism that keeps us alive.

But we also need to make an effort to control them.

We should at least shift our work objective from working just

for ourselves to doing so for our group.

By shifting our objective away from ourselves to others,

the purity of our desire will increase.

Eventually, the strong desire of a pure mind will prevail.

It has often been my experience, when I am agonizing and worrying

over a purely selfless desire, to suddenly see a solutionto the problem.

I like to think of this as a Higher Power granting me an insight

by letting my desperate but pure desire reach my subconscious mind.

Pursue Profit Fairly

Employees have to achieve profitability for the sake of their enterprise

and their people.

This is nothing to be ashamed of. In the free market where

the principle of free competition functions, the profit we gain is

a just reward for doing business in a rightful manner.

We streamline our operations to deliver high-valued products

to our customers at minimal cost.

Managers and workers earn profit byworking hard.

We should be proud of it.

However, we should not let the pursuit of profit overwhelm us.

We should never succumb to the temptation to seek profit shamelessly.

We must remain on the path of righteousness.

We gain profit fairly through hard work to provide the quality

products our customers demand.

We should never dream of making a fortune at a single stroke

through underhanded means.

For example, at the height of the oil crisis, some executives directed

their companies to hold back their merchandise deliberately and

raise prices.

I wonder how many of these unscrupulous managers are still

in executive offices today.

In a free market, profit is society's reward for those who serve its interests.

Ameba Management

"To drive a car, you need to turn your starter to get your engine going,"

I have been telling my executives.

Likewise, to start a major project, you need managers who share your

passion and use it to motivate their employees.

When Kyocera was building its second plant, I became concerned.

We were a young company, growing rapidly because of our entrepreneurial

passion. But I worried that we might eventually become like any other

large corporation - a bureaucracy without any pioneering passion.

I wanted to raise entrepreneurs in Kyocera.

I thus divided our company into small profit centers called amebas.

Each is a small venture business with one person acting as the leader,

or nucleus. A typical ameba buys everything it needs from outside

the company or from other amebas.

It profits by selling its products and services to others or to outside

customers. Each ameba shares in the passion of the ameba leader,

and is evaluated by its hourly efficiency - the average added value

per work-hour of its members.

Several small amebas make up larger amebas which, in turn,

are grouped into even larger amebas.

Kyocera itself is a gigantic ameba, composed of thousands of amebas

all over the world.

Ignite your managers with your passion, so they may ignite passion

in their subordinates.

Pricing is Management

I tell my staff that pricing is management.

It is commonly believed that your price should be slightly

below the market price to compete in the marketplace.

You may lower your profit and sell as much as you can;

or you can price your goods near the market price,

maximize your margin, and expect to sell a lower quantity.

There is an infinite choice of pricing.

In other words, we try to maximize the mathematical product

of the quantity sold times the average selling price.

But many factors influence sales.

No simple answer is found.

It is very difficult to estimate the volume of sales

at any given profit margin.

But, because this pricing will have such an important influence

on business performance.

I believe that only the top management should ultimately set prices.

In pricing, the goal is to find the maximum price customers

will be happy to pay for your product. If it is too high,

customers will not buy.

If it is too low, customers may be happy but gross margin may be

inadequate to maintain your operation no matter how much you sell.

The philosophy at the top will decide the pricing.

An aggressive manager will set an aggressive price

while a cautious manager will price conservatively.

Pricing affects business performance.

It is a reflection of management's capability and philosophy.

Market-set Pricing

In pricing, I don't start from the cost accounting concept.

That is, I don't establish a price by using a preset profit margin

in this common formula:

Price =Cost of Goods + Overhead Costs + Profit

Generally, price is decided by the free-market mechanism.

In short, the customers decide the price.

Since the price is decided by the market, we must continually

minimize our manufacturing costs. The difference between our cost

of goods and our price is the base for our gross profit.

That means our effort to minimize manufacturing costs is, in fact,

an effort to maximize our profit.

To minimize manufacturing costs, we should eliminate all preconceptions

and common knowledge, such as worrying about the ideal percentages of

material cost, labor cost, overhead expenses, and so on.

We should scrutinize all areas and eliminate any unnecessary expenses.

We have to come up with the least costly method of manufacturing

our product with the quality and price the market demands.

In this sense, a penny saved is, indeed, a penny earned.

Maximizing profit while fully satisfying our customers' needs and desires

- this is the essence of business!

After-tax Profit

Think of taxes as necessary business expenses paid

to support the communities in which we operate.

For business executives, paying taxes is as painful as cutting our

own flesh. Each year, we have to surrender more than half of

the profit we worked so hard to earn.

And even though some of our profits are in receivables and other

noncash forms, we still have to pay our tax in cash.

Taxation is merciless!

Perhaps only executives can appreciate this feeling.

Employees may think it's just the company's money.

But for us, it almost feels like someone is stealing our savings.

That's why some executives will resort to any cheap trick to avoid

paying taxes.

This, of course, is wrong.

A company's profit does not belong to the executives.

Further, the taxes we pay are used to benefit society.

We should not selfishly hide our profit from taxation.

To avoid "tax resentment," we must look at our profit objectively

for what it is. Profit is a grade or a score, like in a game, of the credit

that society gives us in return for our contribution.

When I look at profit that way, I can be more objective and not so

possessive. In other words, only after-tax net profit is the true profit.

Taxes are business expenses which we must incur.

After-tax profit is the only profit given to us for our business efforts.

Taxes are our necessary business expenses

Some owners of very profitable businesses deliberately take measures

to keep their profit low. In other words, they splurge on lavish

entertainment, boondoggle trips, and unnecessary expenses to reduce

taxable income.

It is true that more than half our profit is taken away each year

in taxes.

Still, the rest is left to the company. The true spirit of business

management should be to cherish the after-tax profit.

It is said that the equity ratios of most Japanese companies are

very low because of Japan's tax system. I rather think it is

a matter of the philosophy of business executives.

No matter how much we have to pay in taxes, we must never stop

our efforts to raise our profitability.

I now treat taxes as a part of our necessary business expenses, and

assiduously accumulate after-tax profits within our company.

Today, we have hefty internal reserves which provide stability

and flexibility to our company and work opportunities for our employees.

This strength also enables us to tackle challenging new ventures.

Set a Visible Goall

When we set our annual master plan, I challenge myself and others

against setting low, easily attainable targets.

Rather, I want each ameba to have ambitious goals based upon our

strong desire to achieve.

I say, "Boast and then make it come true."

Even though someone may fail to achieve his or her plan,

I do not necessarily go after the results only. But this does not

mean it is all right to let our plans go unachieved;

if the plan continues to be unachieved year after year,

our employees will lose their confidence and ability to attain goals.

It is important to meet our targets.

Everyone has to share the same goal to achieve a target.

If the only people interested in attaining the goal were top executives,

the goal would never be achieved.

Structure your company so that even the smallest units of

the organization have their own plans.

Persuade each person to work hard to pursue his or her part of the plan

and to help the division meet its plan.

Then, as each ameba's plan is met, the overall plan for the organization

will be accomplished as a matter of course.

Set plans every month to translate the annual plan intoa more tangible

and motivating target.

A master plan must be shared with all employees and translated into goals

that are ardently desired by all.

Any Economy has been operatng on a cycle

When a recession hits, many business owners look to government

for a solution. They ask for additional spending, tax cuts, or

lower interest rates to stimulate growth.

Everyone seems to have his or her own opinion.

In truth, any economy has good and bad periods - and no single cycle

has ever lasted forever. Japan, for example, has experienced many

recessions of varying degree and used each one as a stepping stone

to the next phase of growth.

On the whole, Japan's economy has progressed continually upward.

But because of this historic background, many Japanese managers

erroneously believe that their economy will keep growing forever.

The most fundamental fact is that any economy has been operating

on a cycle. The bull and the bear are facts of life, and preparing

for bad times during the good is the most basic rule of management.

Unfortunately, many of today's managers have forgotten this rule

and have become weak-kneed - dependent on government or

some divine intervention for a recovery.

In my opinion, the term "management" should refer to managing

- building a reserve during good times so a recession won't leave

us crying for help.The cycle of good and bad times is a matter of

course in business.

In fact, a painful recession teaches managers something precious:

it instills within their hearts the desire to manage conservatively

during the "boom," and to build a reserve that can outlast

the inevitable "bust."

During Japan's so-called "bubble economy," however, anyone could

get rich by simply buying land or stock. Debts of millions of dollars

were nothing to worry about. Money came easily in vast amounts

as if it simply bubbled up from nowhere.

Yet nobody ever sounded a warning, and hardly anyone exercised

restraint. Instead, an entire generation kept silent as the profits rolled

in - and then, at the sight of the first loss, we panicked.

This mentality also led the stock market into a "loss-compensation"

scandal. At that time, people were getting rich in stocks by simply

entrusting large sums of money with securities firms.

Once these people began to lose money, they had the nerve to demand

compensation - and they got it!

Bulls and bears are the basic tenets of trading.

Corporate financiers have attempted to defy this rule, almost

as if they could defy gravity - and had they succeeded,

they might have destroyed the entire stock market.

Be the Center of possitive achieving action

- Vortex Center

There are three basic types of materials.

They are combustible material, noncombustible material, and

very slowly combustible material.

Combustible material begins to burn when it comes near a fire.

Noncombustible material does not burn, even when it is in the fire.

Very slowlycombustible material begins to burn when it become

too hot from inside.

I classify human beings in the same way.

The most productive person is a very slowly combustible man and

woman when they become a selfstarter. Because enthusiasm and

passion in their minds are the basic factors necessary for achieving

anything.

A noncombustible person is one who may be talented, but is nihilistic

and insensitive, and are usually unable to feel emotion and passion.

Noncombustible people are usually unable to accomplishanything

difficult in spite of their abilities with no enthusiasm and no passion

.

Combustible people can at least become motivated when surrounded

by motivated people. They can at least start burning when they come

near motivated people.

We really need motivated people who have become fired up with

their own energy. Such people can burn and give energy to others

around them. You must engulf others in your enthusiasm and passion.

There is a limit to what one person alone can achieve. In your work,

you have to cooperate with people around you - your supervisors,

subordinates, and colleagues.

However, you should aggressively pursue your work so the people

around you will be spontaneously cooperate with you.

This is what I call "working in the center of the possitive achieving action."

You might end up being outside the possitive achieving action

with someone else in the center of it. In a company there are many

business , the possitive achieving actions like currents eddying everywhere.

If you are just floating around them, you will be engulfed in them.

To experience the real joy and zest of work, you have to be in the center

of the possitive achieving actions - vortexes, and tackle your job as

aggressively as if you were engulfing the other people around you.

Whether or not your way of thinking is independent aggressive enough

to create your own possitive achieving action will decide only the result

of your work, but also the result of your life.

The Transformations

driven by

the Fourth Industrial

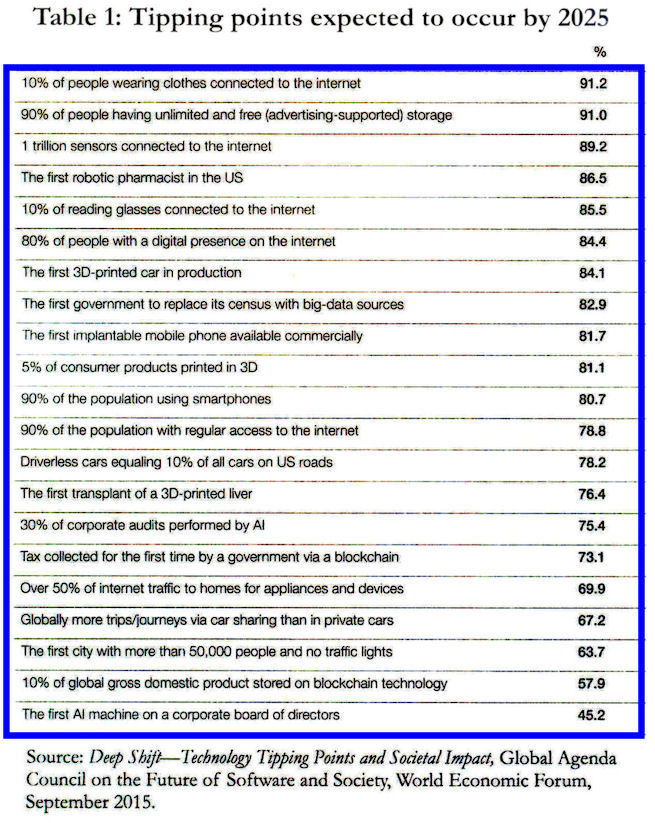

Revolution

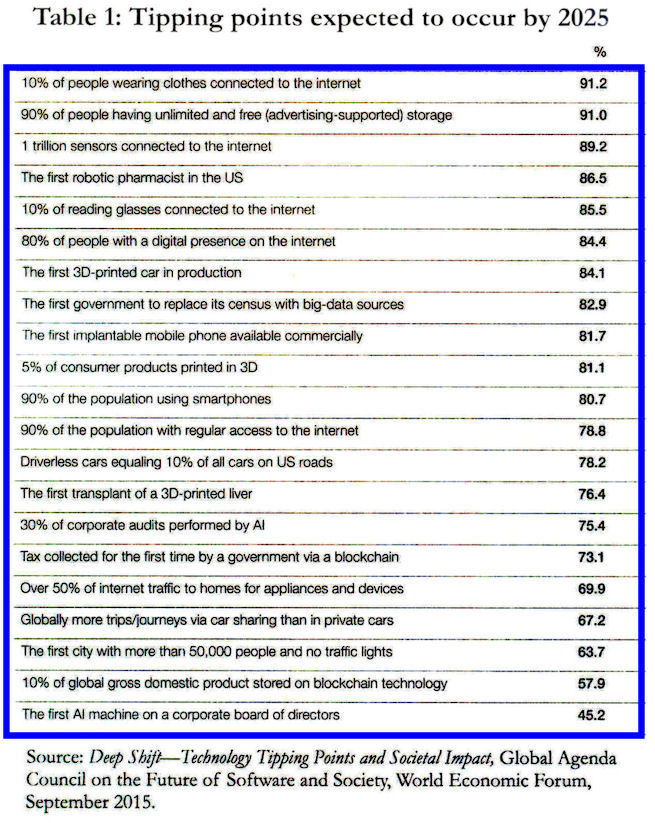

from World Economic Forum in 2016

Introduction

Of the many diverse and fascinating challenges we face today,

the most intense and important is how to understand and shape

the new technology revolution, which entails nothing less than

a transformation of humankind.

We are at the beginning of a revolution that is fundamentally

changing the way we live, work, and relate to one another.

In its scale, scope and complexity, what I consider to be the fourth

industrial revolution is unlike anything humankind has experienced

before.

We have yet to grasp fully the speed and breadth of this new revolution.

Consider the unlimited possibilities of having billions of people connected

by mobile devices, giving rise to unprecedented processing power,

storage capabilities and knowledge access.

Or think about the staggering confluence of emerging technology

breakthroughs, covering wide-ranging fields such as artificial intelligence

(AI), robotics, the internet of things (IoT), autonomous vehicles,

3D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science,

energy storage and quantum computing, to name a few.

Many of these innovations are in their infancy, but they are already

reaching an inflection point in their development as they build on

and amplify each other in a fusion of technologies across the physical,

digital and biological worlds.

We are witnessing profound shifts across all industries, marked

by the emergence of new business models, the disruption' of

incumbents and the reshaping of production, consumption, transportation

and delivery systems.

On the societal front, a paradigm shift is underway in how we work

and communicate, as well as how we express, inform and entertain

ourselves.

Equally, governments and institutions are being reshaped, as are systems

of education, healthcare and transportation, among many others.

New ways of using technology to change behavior and our systems

of production and consumption also offer the potential for supporting

the regeneration and preservation of natural environments, rather than

creating hidden costs in the form of externalities.

The changes are historic in terms of their size, speed and scope.

While the profound uncertainty surrounding the development and

adoption of emerging technologies means that we do not yet know

how the transformations driven by this industrial revolution will unfold,

their 'complexity and interconnectedness across sectors imply that

all stakeholders of global society --governments, business, academia,

and civil society --have a responsibility to work together to better

understand the emerging trends.

Shared understanding is particularly critical if we are to shape

a collective future that reflects common objectives and values.

We must have a comprehensive and globally shared view of

how technology is changing our lives and those of future generations,

and how it is reshaping the economic, social, cultural and human

context in which we live.

The changes are so profound that, from the perspective of human history,

there has never been a time of greater promise or potential peril.

My concern, however, is that decision makers are too often caught

in traditional, linear (and nondisruptive) thinking or too absorbed

by immediate concerns to think strategically about the forces of

disruption and innovation shaping our future.

I am well aware that some academics and professionals consider

the developments that I am looking at as simply a part of

the third industrial revolution.

Three reasons, however, underpin my conviction that a fourth and

distinct revolution is under way:

Velocity:

Contrary to the previous industrial revolutions, this one is evolving

at an exponential rather than linear pace. This is the result of

the multifaceted, deeply interconnected world we live in and

the fact that new technology begets newer and ever more capable

technology.

Breadth and Depth:

It builds on the digital revolution and combines multiple technologies

that are leading to unprecedented paradigm shifts in the economy,

business, society, and individually. It is not only changing the "what"

and the "how" of doing things but also "who" we are.

Systems Impact:

It involves the transformation of entire systems, across (and within)

countries, companies, industries and society as a whole.

In writing this book, my intention is to provide a primer

on the fourth industrial revolution

- what it is, what it will bring, how it will impact us, and

what can be done to harness it for the common good.

This volume is intended for all those with an interest

in our future who are committed to using the opportunities of

this revolutionary change to make the world a better place.

I have three main goals:

--to increase awareness of the comprehensiveness and

speed of the technological revolution and its multifaceted

impact,

--to create a framework for thinking about the technological

revolution that outlines the core issues and highlights

possible responses, and

--to provide a platform from which to inspire public-private

cooperation and partnerships on issues related to

the technological revolution.

Above all, this book aims to emphasize the ways in which

technology and society coexist.

Technology is not an exogenous force over which we have

no control.

We are not constrained by a binary choice between

"accept and live with it" and "reject and live without it."

Instead, take dramatic technological change as an invitation

to reflect about who we are and how we see the world.

The more we think about how to harness the technology

revolution, the more we will examine ourselves and

the underlying social models that these technologies embody

and enable, and the more we will have an opportunity to shape

the revolution in a manner that improves the state of the world.

Shaping the fourth industrial revolution to ensure that it is

empowering and human-centered, rather than divisive and

dehumanizing, is not a task for any single stakeholder

or sector or for any one region, industry or culture.

The fundamental and global nature of this revolution means

it will affect and be influenced by all countries, economies,

sectors and people.

It is, therefore, critical that we invest attention and energy

in multistakeholder cooperation across academic, social, political,

national and industry boundaries.

These interactions and collaborations are needed to create

positive, common and hope-filled narratives, enabling individuals

and groups from all parts of the world to participate in, and

benefit from, the ongoing transformations.

Much of the information and my own analysis in this book

are based on ongoing projects and initiatives of the World

Economic Forum and have been developed, discussed

and challenged at recent Forum gatherings.

Thus, this book also provides a framework for shaping the future

activities of the World Economic Forum.

I have also drawn from numerous conversations I have had

with business, government and civil society leaders, as well as

technology pioneers and young people.

It is, in that sense, a crowd-sourced book, the product of

the collective enlightened wisdom of the Forum's communities.

This book is organized in three chapters.

The first is an overview of the fourth industrial revolution.

The second presents the main transformative technologies.

The third provides a deep dive into the impact of the revolution

and some of the policy challenges it poses. I conclude

by suggesting practical ideas and solutions on how best to adapt,

shape and harness the potential of this great transformation.

1. The Fourth Industrial Revolution

1.1 Historical Context

The word "revolution" denotes abrupt and radical change..

Revolutions have occurred throughout history when new technologies

and novel ways of perceiving the world trigger a profound change

in economic systems and social structures.

Given that history is used as a frame of reference,

the abruptness of these changes may take years to unfold.

The first profound shift in our way of living --the transition

from foraging to farming--happened around 10,000 years ago

and was made possible by the domestication of animals.

The agrarian revolution combined the efforts of animals with those

of humans for the purpose of production, transportation and

communication.

Little by little, food production improved, spurring population

growth and enabling larger human settlements. This eventually

led to urbanization and the rise of cities.

The agrarian revolution was followed by a series of industrial

revolutions that began in the second half of the 18th century.

These marked the transition from muscle power to mechanical

power, evolving to where today, with the fourth industrial revolution,

enhanced cognitive power is augmenting human production.

The first industrial revolution spanned from about 1760 to around 1840.

Triggered by the construction of railroads and the invention of the steam

engine, it ushered in mechanical production.

The second industrial revolution, which started in the late 19th century

and into the early 20th century, made mass production possible,

fostered by the advent of electricity and the assembly line.

The third industrial revolution began in the 1960s.

It is usually called the computer or digital revolution because it was

catalyzed by the development of semiconductors, mainframe

computing (1960s), personal computing (1970s and '80s) and

the internet (1990s).

Mindful of the various definitions and academic arguments used

to describe the first three industrial revolutions, I believe that

today we are at the beginning of a fourth industrial revolution.

It began at the turn of this century and builds on the digital revolution.

It is characterized by a much more ubiquitous and mobile internet,

by smaller and more powerful sensors that have become cheaper,

and by artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Digital technologies that have computer hardware, software and

networks at their core are not new, but in a break with the third

industrial revolution, they are becoming more sophisticated and

integrated and are, as a result, transforming societies and

the global economy.

This is the reason why Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have famously

referred to this period as "the second machine age,"

the title of their 2014 book, stating that the world is at an inflection

point where the effect of these digital technologies will manifest with

"full force" through automation and and the making of

"unprecedented things."

The first industrial revolution spanned from about 1760

to around 1840. Triggered by the construction of railroads

and the invention of the steam engine, it ushered in

mechanical production.

The second industrial revolution, which started in the late

19th century and into the early 20th century, made

mass production possible, fostered by the advent of electricity

and the assembly line.

The third industrial revolution began in the 1960s. It is usually

called the computer or digital revolution because it was catalyzed

by the development of semiconductors, mainframe computing (1960s),

personal computing (1970s and '80s) and the internet (1990s).

Mindful of the various definitions and academic arguments

used to describe the first three industrial revolutions, I

believe that today we are at the beginning of a fourth

industrial revolution. It began at the turn of this century

and builds on the digital revolution.

It is characterized by a much more ubiquitous and mobile internet,

by smaller and more powerful sensors that have become cheaper,

and by artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Digital technologies that have computer hardware, software

and networks at their core are not new, but in a break

with the third industrial revolution, they are becoming

more sophisticated and integrated and are, as a result,

transforming societies and the global economy.

This is'the reason why Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have

famously referred to this period as "the second machine

age," the title of their 2014 book, stating that the world

is at an inflection point where the effect of these digital

technologies will manifest with "full force" through

automation and and the making of "unprecedented things."

In Germany, there are discussions about "Industry 4.0,"

a term coined at the Hannover Fair in 2011 to describe

how this will revolutionize the organization of global

value chains. By enabling "smart factories," the fourth

industrial revolution creates a world in which virtual and

physical systems of manufacturing globally cooperate

with each other in a flexible way. This enables the absolute

customization of products and the creation of new

operating models.

The fourth industrial revolution, however, is not only about

smart and connected machines and systems. Its scope is

much wider. Occurring simultaneously are waves of further

breakthroughs in areas ranging from gene sequencing to

nanotechnology, from renewables to quantum computing.

It is the fusion of these technologies and their interaction

across the physical, digital and biological domains that make

the fourth industrial revolution fundamentally different

from previous revolutions.

In this revolution, emerging technologies and broad-based

innovation are diffusing much faster and more widely than

in previous ones, which continue to unfold in some parts

of the world. This second industrial revolution has yet to

be fully experienced by 17% of world, as nearly 1.3 billion

people still lack access to electricity.

This is also true for the third industrial revolution,

with more than half of the world's population,

4 billion people, most of whom live in the developing world,

lacking internet access. The spindle

(the hallmark of the first industrial revolution) took almost

120 years to spread outside of Europe.

By contrast, the internet permeated across the globe

in less than a decade.

Still valid today is the lesson from the first industrial

revolution--that the extent to which society embraces

technological innovation is a major determinant of

progress.

The government and public institutions, as well as

the private sector, need to do their part, but it is also

essential that citizens see the long-term benefits.

I am convinced that the fourth industrial revolution will be

every bit as powerful, impactful and historically important

as the previous three.

However, I have two primary concerns about factors

that may limit the potential of the fourth industrial revolution

to be effectively and cohesively realized.

First, I feel that the required levels of leadership and

understanding of the changes under way, across all sectors,

are low when contrasted with the need to rethink our

economic, social and political systems to respond to the

fourth industrial revolution. As a result, both at the national

and global levels, the requisite institutional framework

to govern the diffusion of innovation and mitigate the

disruption is inadequate at best and, at worst, absent

altogether.

Second, the world lacks a consistent, positive and common

narrative that outlines the opportunities and challenges

of the fourth industrial revolution, a narrative that is

essential if we are to empower a diverse set of individuals

and communities and avoid a popular backlash against the

fundamental changes under way.

1.2 Profound and Systemic Change

The premise of this book is that technology and digitization will

revolutionize everything, making the overused and often ill-used

adage "this time is different" apt.

Simply put, major technological innovations are on the brink of

fueling momentous change throughout the world--inevitably so.

The scale and scope of change explain why disruption and innovation

feel so acute today. The speed of innovation in terms of both

its development and diffusion is faster than ever.

Today's disruptors (Airbnb, Uber, Alibaba and the like--now household

names) were relatively unknown just a few years ago. The ubiquitous

iPhone was first launched in 2007. Yet there will be as many as 2 billion

smartphones by the end of 2015. In 2010 Google announced its first

fully autonomous car. Such vehicles could soon become a widespread

reality on the road.

One could go on. But it is not only speed; returns to scale

are equally staggering.

Digitization means automation, which in turn means that

companies do not incur diminishing returns to scale

(or less of them, at least).

To give a sense of what this means at the aggregate level,

compare Detroit in 1990 (then a major center of traditional

industries) with Silicon Valley in 2014. In 1990, the three

biggest companies in Detroit had a combined market

capitalization of $36 billion, revenues of $250 billion,

and 1.2 million employees. In 2014, the three biggest

companies in Silicon Valley had a considerably higher

market capitalization ($1.09 trillion), generated roughly

the same revenues ($247 billion), but with about 10 times

fewer employees (137,000).

The fact that a unit of wealth is created today with much

fewer workers compared with 10 or 15 years ago is possible

because digital businesses have marginal costs that tend

towards zero.

Additionally, the reality of the digital age is that many new

businesses provide "information goods" with storage, transportation

and replication costs that are virtually nil.

Some disruptive tech companies seem to require little capital

to prosper. Businesses such as Instagram or WhatsApp, for example,

did not require much funding to start up, changing the role of capital

and scaling business in the context of the fourth industrial revolution.

Overall, this shows how returns to scale further encourage scale and

influence change across entire systems.

Aside from speed and breadth, the fourth industrial revolution is unique

because of the growing harmonization and integration of so many

different disciplines and discoveries.

Tangible innovations that result from interdependencies among different

technologies are no longer science fiction. Today, for example, digital

fabrication technologies can interact with the biological world.

Some designers and architects are already mixing computational design,

additive manufacturing, materials engineering and synthetic biology

to pioneer systems that involve the interaction among micro-organisms,

our bodies, the products we consume, and even the buildings weinhabit.

In doing so, they are making and even "growing" objects that are

continuously mutable and adaptable hallmarks of the plant and animal kingdoms;

In The Second Machine Age, Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that computers

are so dexterous that it is virtually impossible to predict what applications they

may be used for in just a few years. Artificial intelligence(AI) is all around us,

from self-driving cars and drones to virtual assistants and translation software.

This is transforming our lives.

AI has made impressive progress, driven by exponential increases in computing

power and by the availability of vast amounts of data, from software

used to discover new drugs to algorithms that predict our cultural interests.

Many of these algorithms learn from the "bread crumb" trails

of data

that we leave in the digital world. This results in new types of "machine

learning" and automated discovery that enable "intelligent"

robots and

computers to self-program and find optimal solutions from first principles.

Applications such as Apple's Siri provide a glimpse of the power of one

subset of the rapidly advancing AI field -- so-called intelligent assistants

Only two years ago,intelligent personal assistants were starting toemerge

Today, voice recognition and artificial intelligence are progressing so

quickly that talking to computers will soonbecome the norm, creating

what some technologists call ambient computing, in which robotic

personal assistants are constantly available to take notes and respond

to user queries.

Our devices will become an increasing part of our personal ecosystem,

listening to us,anticipating our needs, and helping us when required

-- even if not asked.

Inequality as a systemic challenge

The fourth industrial revolution will generate great benefits and big

challenges in equal measure. A particular concern is exacerbated

inequality. The challenges posed by rising inequality are hard

to quantify as a great majority of us are consumers and producers,

so innovation and disruption will both positively and negatively affect

our living standards and welfare. The consumer seems to be gaining

the most.

The fourth industrial revolution has made possible new products and

services that increase at virtually no cost the efficiency of our personal

lives as consumers.

Ordering a cab, finding a flight, buying a product, making a payment

listening to music or watching a film--any of these tasks can now

be done remotely.

The benefits of technology for all of us who consume are

incontrovertible.

The internet, the smartphone and the thousands of apps are making

our lives easier, and--on the whole--more productive.

A simple device such as a tablet, which we use for reading, browsing

and communicating, possesses the equivalent processing power of

5,000 desktop computers from 30 years ago, while the cost of storing

information is approaching zero (storing 1GB costs an average of less

than $0.03 a year today, compared with more than $10,000, 20 years

ago).

The challenges created by the fourth industrial revolution appear to be

mostly on the supply side--in the world of work and production.

Over the past few years, an overwhelming majority of the most

developed countries and also some fast-growing economies such as

China have experienced a significant decline in the share of labor as

a percentage of GDP.

Half of this drop is due to the fall in the relative price of investment

goods,' itself driven bythe progress of innovation (which compels

companies to substitute labor for capital).

As a result, the great beneficiaries of the fourth industrial

revolutionarethe providers of intellectual or physical capital

--the innovators, the investors, and the shareholders, which

explains the rising gap in wealth between those who depend

on their labor and those who own capital.

It also accounts for the disillusionment among so many workers,

convinced that their real income may not increase over their lifetime

and that their children may not have a better life than theirs.

Rising inequality and growing concerns about unfairness present such

a significant challenge that I will devote a section to this in Chapter

Three.

The concentration of benefits and value in just a small percentage of

people is also exacerbated by the so-called platform effect, in which

digitally driven organizations create networks that match buyers and