by Hugh Cortazzi

関連サイト:ウィリス医師の東北戦争従軍記録

While Edo was returning to normal and

peace had been largely restored in the area around Edo,

disturbances continued elsewhere, especially in the north east.

Willis's medical services had been much appreciated,

especially by the leaders of the Satsuma forces,

and Parkes was asked to release Willis

to accompany the Imperial forces in their campaign and

help with the wounded.

Parkes readily agreed and

Willis, who was always anxious to do what he could as a doctor

to relieve suffering, was glad to go.

He left Edo on 5 October and returned on 28 December 1868.

His reports to Parkes make fascinating reading and

show clearly the problems with which he had to cope in his efforts

to inculcate the first principles of Western medicine.

His first two letters and three memoranda were forwarded

by Parkes to Hammond, the Permanent Under-Secretary

in the Foreign Office, on 4 November.

Parkes commented:

'I have little to say on my own part by this mail

but I think I am sending you more interesting reading matter

than usual.'

Dr Willis's `plain unvarnished statements . . .

may aid materially in forming a judgement as to the probable issue

of the present contest.

There is now good reason to hope that the Mikado's authority

will be universally established.'

Parkes stressed that Willis's memoranda

'have only been sent to me privately and that I forward them now

as information only which should not be made public.

He speaks of them himself as crude notes and I feel that

before any official use is made of them,

he should be allowed the opportunity of revision.'

In his first letter to Parkes from Takata dated 16 October

Willis wrote:

I have to report my arrival here today safe, and if not sound,

it only amounts to a cold caught on the way, which will be well

in a day or two . . .

At the barrier guard house at a place called Sekigawa(関川=信越本線妙高高原駅),

eight ri [leagues] from this, I was rudely ordered to take off my hat

as I passed the guard house and altogether very unceremoniously treated.

I demanded an apology from the chief official of the guard house

and permission to go through the barrier without any insolence

from the guards.

These terms being refused by the chief of the guards,

I declined to proceed on my journey until I had received satisfaction.

A letter was thereupon sent off to Takata(高田) and two officers of that place

came and ordered the chief of the guards to apologise for their rudeness.

The next morning I passed through the barrier unmolested and

the chief of the guards came out and made a second apology

for the rudeness of the previous day.

I hope you will approve of my proceedings.

I should not care to push matters too far as the chief of the guards said

that if he had committed any serious offence he would be ready,

as a Samurai,

to perform the [hara-kiri].

The treatment I received at the barrier was so unlike anything I had

elsewhere met with and was so rude and violent that redress became

necessary, although it cost me a day on the road longer than

I would otherwise have been.

After the apology I promised that the whole thing should be forgotten.

I explained fully to them that I could not proceed on my journey and

at the same time be treated insolently, that in my position coming here

at the instance of the Japanese government I should expect civility, and

though in some cases I might overlook a want of courtesy, I would

under no circumstances submit to rudeness.

Lastly, I told them that in passing barriers through which foreigners had

a right to go, they did not take off their hats, unless, indeed, in cases

where they acknowledged the salute of the guard of the place,

but all this was a matter of courtesy.

It was quite a different question when a rude order in a violent way

was given. The guard house is in the keeping of the Daimyo of this place.

He is named Sakakibara. I was told that he regretted the affair very much.

In the accompanying memorandum from Takata dated 17 October 1868,

Willis submitted some observations on the state of the country through

which he had travelled:

Every where I passed through the present government seemed

to be accepted and the people generally think the recent changes of

government promise a better state of things for the future . . .

It would appear that the hatamoto [middle- ranking Samurai] of

the Tycoon's government were very oppressive landlords.

注:ウィリスがhatamotoと言っているのは小藩のこと。

当時、大中小合わせて274もの藩があつた。

It is expected that more uniformity and justice in the amount of

tribute assessed on government land will exist in the future.

I failed to obtain any evidence of sympathy with the old regime

from any natives . . .

The authority of the government seemed everywhere recognised,

barriers opened and inns (honjin) admitted me as an official

travelling at the instance of the government of the country.

Wherever I stopped for the night or for my midday meal, the village

yakunin in their official dress came out to meet and escort me and

the obeisances I met with in many places were impressive.

I could discover no sympathy with the Northern party who are now

fighting, and all I could hear was that the Tycoon's government having

been abolished, it was impossible for the old regime to be restored . . .

The little shop keepers and trades people all along the way regretted

the absence of the traffic of old, when Daimyo and their retainers

spent money freely on the road.

The ancient custom of the Daimyos necessarily residing in Edo was

looked upon as a thing of the past and in no case likely to be revived.

In the silk districts the money that changes hands is so considerable

that inn keepers speak of it as in some measure compensating

for the old traffic . . .

I was pleased with the freedom I enjoyed in making the journey and

all who accompanied me obtained for me any information

that I required of them and did not conceal or make frivolous objection

to small things like the suspicious officials of the old regime.

I saw no traces of fighting or burning of villages as I came along ;

there was nothing indeed to mark a civil commotion that fell under

my eyes and all people seemed to pursue their ordinary avocations.

I had occasion to observe the great want in Japan of a real central government.

There are no public works of any importance ;

in places close to Edo the roads were certainly the worst I had ever seen,

the mud was knee deep, and with the utmost effort it was in places

impossible to get over twenty miles in a day.

There were no bridges of any importance spanning rivers ;

all traffic is depending upon ferries of the most primitive character . . .

I observed government notices stuck up in all towns along the way,

announcing the recent changes in the govern ment of Japan and

making provision for the better treatment of foreigners . . .

As I passed along I saw notices of the execution of robbers at three places.

It appears that robbery had grown very common in Musashi

[a province near Edo]; armed ruffians were in the habit of extorting money

from the farmers, and to put a stop to this the law was being put in force

with somewhat unusual promptness and severity.

It must be confessed, however, that the Japanese police system is very imperfect,

and from what one hears, there appears to be great impunity attending

the violence of two-sworded ruffians.

Willis, who was conscious of his commercial responsibilities as a Vice-Consul,

commented on the 'unusually good silk crop' :

On enquiry about the price I found it was not very different from Yokohama

quotations and I certainly could not hear of any heavy imposts being put

upon it along the way.

The silk farmers seem to have good times of it. I was told that during

the last ten years silk had risen in price five and six fold . . .

I was told that the amount of land under silk cultivation grows greater

every year and that in some districts of Musashi it has doubled within

the last few years. In the great Edo plain . . .the cultivation of the mulberry

is certainly immense.

It appears to me that there was scarcely any limit to the amount of silk

that might be produced, were it not that Japanese attach first importance

to rice crops, partly I imagine due to the circumstance that it is in this

commodity that the rent of the land is paid, and rice must be in any case

forthcoming.

The rains had been very heavy. 'In many places near the river banks

the rice crop has been completely destroyed by inundations.'

The cotton crop had also failed. Beyond the Usui pass

(near Karuizawa in present Nagano prefecture)

he 'found the Irish potato growing in small quantities.

It appears to have been grown in these parts for a period

beyond the memory of any one I met.

It seems to flourish and is quite free from disease.

It however finds no great favour amongst the Japanese.'

He noticed especially in the uplands 'almost every English

roadside plant . . .

There was a marked absence, however, of animal life,

though I was told that later on in the season many birds come

for the winter and that deer, wild bears and wolves are to be seen.

Hares, pheasants and pigeons are to be bought, but their prices are

higher than at Yokohama, the cause alleged being that

as fish is scarce inland the price of all sorts of fowls is kept up.'

Willis was not complimentary about the 'natives':

I must say that my impression as regards the Japanese I saw

along the way is unfavourable both physically and mentally.

The women are ugly and the men as a race weak and stupid looking.

I noticed a difference between the inhabitants of the Edo plain and

those inhabitants of the colder and more bracing climate on the West . . .

in favour of the latter . . . I passed many persons and places

to which a foreigner must have been a novel sight, and

yet I was hardly looked at ; in other places I was followed by crowds

in spite of the bad weather.

I may also remark that there appears to be a great difference

between the town and the more strictly rustic population.

Mental activity is much greater in the former than in the latter.

I saw comparatively substantial farm houses here and there . . .

I saw no abject and squalid poverty along the line of my journey.

I noticed an almost entire absence of beggars ; upon enquiry

I heard that there were fewer beggars now than formerly.

The population, I must say, seemed to me to be as thick

on the ground as the character of the country admitted, and

from all I saw I do not think there is room for any great increase.

Many of the villages I passed through seemed to be mere repetitions

of each other.

In some the stench was offensive to a degree.

A large tub(便槽), which is used as a urinal, is sunk in the earth at the corner

of each house, the consequence is that the air of the house is

always vitiated, and I fancy the sickly looks of the inmates may

often be attributed to this unhealthy custom.

I found that brothels (売春宿=遊郭) were common in the larger villages

and towns, and where brothels did not exist the tea house women acted

as prostitutes.

I found evidence of syphilitic disease (梅毒) largely prevalent

amongst the people, and I am disposed to think that great mischief arises

to bodily health from want of knowledge of the disease and its treatment.

I went to see several of the oldest people of the places I stopped

at. At Honjo one old woman whom I saw was stated to be a hundred.

She was certainly very old and shrivelled and was more like

a hundred years old than any person I had ever seen.

Still the comfortless houses of the Japanese and the poor diet

they live upon make me very dubious about any one living

to the extreme age of one hundred in this country.

Even in the best districts of Musashi the villages were poor and shabby

and sometimes on the richest soils I saw the poorest rustic population.

I saw only one really large temple, this was at Zenkoji [Zenkoji

at Nagano City is still much visited by pilgrims. It was founded in 670].

I found the priest civil and intelligent. I was asked to see a sick woman

at this place ; she was the wife of a two-sworded man and in obedience

to the custom prevailing amongst her class had remained in a sitting

posture after her confinement until inflammation of the knee joints and

general dropsy had resulted. The custom appears to cause great suffering

and occasionally serious injury results.

I found that my reputation as a foreign doctor had preceded me,

and I was quite oppressed by people who had been ailing

for the last twenty years.

I saw two persons afflicted with leprosy on the journey

[Willis was to see more cases later in Satsuma]:

it is not common, all spoke of the disease with great abhorrence.

I was told that people afflicted with this disease become beggars

and go into distant provinces.

In one village I found an epidemic of dysentery prevailing ;

great numbers of people had died of the disease.

It was attributed to the badness of the season.

It was confined to one district.

In many of the villages there is a running stream down the centre

of the street covered in partially in some villages and quite open in others.

In a number of places the water appeared to me to be bad and

unwholesome and as if containing the drainage from the houses.

From all I saw I would say the Japanese show great indifference

both as regards air and water.

My guard consisted of twenty-five men of Chikuzen

[a fief in Kyushu], young pleasant fellows.

There also accompained me an officer of Bizen, named Mizuta Kenzo,

who kept the purse.

I was also accompanied by a Doctor of the Prince of Bizen and

a young Doctor of Satsuma ; the latter is a relation of Terashima,

the Yokohama governor.

My own retainers were a native teacher, a cook and a personal

servant ; to the first I am much indebted for what I learnt on the way.

For many reasons it would have been impossible or impolitic

to make certain enquiries that only a native could make quietly and

with considerable circumspection.

My guardians treated me well, and I have not a word of complaint

to make, but guardianship is occasionally like imprisonment and

I found some times embarrassment at not being left alone to pursue

my enquiries. I must say, however, that my wishes were well met

on all sides.

I saw along the road a number of packhorses and bulls laden

with rice, silk, fish manure, salt, tobacco, etc.

Still the road was not a busy one and, in this respect,

fell far short of what I expected, considering its importance.

The bad weather may have in a great degree prevented traffic ;

it rained less or more every day and some days from morning till night.

The silk was going to Edo for the Yokohama market.

The only towns worthy of note I saw on the way were Takasaki,

Ueda and Zenkoji [Nagano] ; the two former are Daimyo's

residences, and a good deal of business seems to be transacted

in them.

Some pretty silk fabrics are made at Ueda. It is woven

by the farmers some distance from the town.

In the towns, however, I could discover no important manufactures

going on, all household utensils were obtained from Edo or Kyoto,

except the most primitive.

I saw foreign cotton goods at all the large places of traffic,

but no woollens, the latter would appear to be much required

as one approaches the West Coast . . .

At Ueda I saw an old gentleman nicely dressed, in European clothes,

he was formerly a pupil of Capt. Applin [an officer of the Legation

guard] who taught him cavalry drill ; he bought Capt. Applin's

saddle when the latter left Japan. It was certainly kept in good order

and was on a fine Japanese pony when I saw it.

My journey occupied from various causes twelve days,

the distance is seventy two ri (above one hundred and eighty miles).

The End

参考文献:

ウィリアム・ウィリスの報告書・書簡の集大成:890頁:創泉堂出版 2003年発行

The End

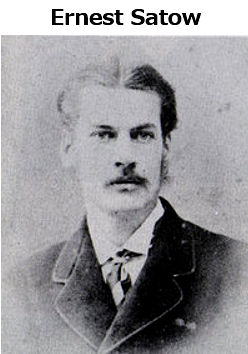

British diplomat Ernest Satow

at the time of shogunate's surrender

Historically speaking, two key figures ? Katsu Kaishu, the shogunate's

army minister, and Saigo Takamori, head of the Imperial forces ?

negotiated the conditions of the shogunate's surrender, leading to

the bloodless fall of Edo Castle and Emperor Meiji's restoration to power.

But in “Edo-jo Muketsu Kaijo” (“The Bloodless Fall of Edo),”

airing Sunday on BS Premium, a new theory will assert that Satow,

one of the most influential non-Japanese figures at the time, played

a key role in encouraging Saigo and other feudal lords to oust the shogunate.

A series of articles he wrote in The Japan Times in 1866 claimed that

ultimate power rests with the emperor, not the Tokugawa shogunate.

Some historians feel these articles served to encourage the Imperial forces.

“We gravely and seriously advocate a radical change. What we want is

not a treaty with a single potentate, but one binding on and advantageous

to every one in the country,” Satow wrote in an article published

on Mar. 16, 1866.

Two months after, in the final article of the series on May 19,

he concluded that the country desired “a fair and equitable Convention

with the MIKADO and the Confederate Daimios ? the real rulers of Japan.”

“The Japan Times article was translated and was made into a book titled

‘Eikoku Sakuron’ (‘British policy’). With Britain heading the diplomatic

corps (in Japan), it pushed the backs of groups that were against

the shogunate, having written that the sovereignty of Japan lies

with the emperor, not the shogunate, and that the shogun is just being

entrusted with the authority from the emperor,” said Masakazu Taniguchi,

the chief producer of the show.

The book was read by the leaders of the Satsuma and Choshu domains,

including Saigo, he said.

Back then, in 1865, Charles Rickerby, a British manager at The Central Bank

of Western India, the first bank to be established in Yokohama,

bought The Japan Commercial News, a local English-language newspaper,

and renamed it The Japan Times. This paper was renamed The Japan Mail

in 1870. The Japan Mail was later acquired in 1918 by the current Japan Times,

a separate entity established in 1897 as the first English-language newspaper

in the nation to be run and managed by Japanese.

Satow served as a translator for Harry Parkes, a British minister,

and had close ties with Rickerby. The first edition of The Japan Times

in 1865 ran a story on problems related to the Tokugawa shogunate’s

reluctance to open Kobe port to foreign traders.

The move prompted “Britain to give up on the shogunate. They wondered,

‘When do we get to conduct trades in Hyogo?’ ” said Taniguchi,

adding that Japan was a cash cow for Britain.

In 1867, the shogunate returned its political power to the emperor.

The shogunate, however, declared that politics will still be decided

by a congress of feudal lords and the monarch, which left Saigo doubtful.

Saigo later formed the Imperial army and demanded the official positions

and territories of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Knowing that Saigo’s army would be attacking Edo, the capital,

Katsu moved to negotiate with him, saying that he would hand

over Edo Castle if Saigo agreed not to use force. The castle thus fell

in a bloodless surrender ? a move that saved the lives of about a million

residents of the city, which would later be renamed Tokyo.

Katsu had also feared foreign countries would take advantage of

the situation. Japan was already suffering under one-sided trade treaties.

“Satow was close not only with those in (the) Satsuma and Choshu

domains, but also with those on the shogunate side, especially Katsu

Kaishu. He had a vast network on both sides,” Taniguchi said.

“He was the perfect person to play a key role in the show, to view

objectively the history that leads to the end of the Edo Period. Plus,

he left many written records,” he said.

Satow is best known as the author of “A Diplomat in Japan,”

a book based on his diaries that recounts the years from 1862 to 1869.

The show is based on a true story and incorporates interviews

with historians including Ukeru Magosaki, a former Foreign Ministry

bureaucrat who heads the East Asian Community Institute, and

Akihiro Machida, an associate professor at Kanda University of

International Studies’ Research Institute for Japanese Studies.

Senior editors from The Japan Times also appear on the program.

NHK BS Premium has run programs on the Edo Period

for the past two years. The first explained the history of Edo Castle,

and the second examined the Great Fire of Meireki that burned down

major parts of the city in 1657.

“Having experts researching based on British documents,

it’s new that we’re seeing the fall of Edo through a British perspective,”

Taniguchi said.

The End

参考サイト:会津戦争 母成峠の戦い