January 2017

Re:

ソ連収容所における日本人捕虜の生活と死

TABLE OF CONTETS

TITLE

Discrepancy Between Soviet and JapaneseRepatriation Totals... I

The Death-Factor In Soviet Prisoner of War Camps............... II

Malnutrition And Lack of Medical Care in Soviet P.W. Camps..III

Soviet Exploitation of Japanese Prisoner of War Labor........ ...IV

Soviet Indoctrination of Japanese Prisoners of War.................V

Communist Indoctrination of Japanese Repatriates..................VI

The Recalcitrant Repatriates: Season 1949...................... .....VII

ILUSTRATIONS

1. Repatriation Statistics.....................................TAB I page 3

2. Map: Soviet PW Camps...................................TAB II page4

3. Flotsaa of War: Displaced Civilian......................TAB IV page 3

4. Recalcitrant Repatriates: 1949..........................TAB VII page 5

5. Communist Interference: 1949 Repatriation.........TAB VII page 6

6. Soviet Repatriates: Men or Beasts?....................TAB VII page 7

Ⅰ

Discrepancy between Soviet

and Japanse Repatriation Figures

Climbing on the band-wagon, Secretary General Kyuichi Tokuda

of the Japan Communist Party addressed a petition to the Soviet

Communist Party Central Committee, in Moscow, on 6 May 1949,

with "comraely greetings" he urged a speed-up of repatriation

of Japanese war prisoners, a serious political issue in Japan.

That the subject had become a burning issue is not strange

since thousands of Japanese families had been waiting

for their men-folk to return since 1945.

As the 1949 repatriation season approached, the Japanese press

made much of the subject.

Mainichi_Shimbun, on 28 April, published a sharp editorial inquiry

into the fate of approximately 400,000 Japanese still unaccounted for.

On the same date Asahi_Shimbun, in a similar plea, listed figures

unaccounted for as 324,000 in Siberia, 84,000 in Sakhalin and the

Kuriles and an estimated 60,000 in the Chinese Communist controlled

areas; Jiji_Shimbun covered the same subject and on the same date.

Moscow radio (Pietersky), obviously touched and embarrassed,

hurriedly answered the Asahi_Shimbufl editoria, with the flimsy

argument that " the prisoners, when. repatriated, are faced with

unemployment and lack of. housing" and that the "Soviet Government

has been spending huge sums of money to feed the Japanese prisoners

of war."

The Japanese spontaneous newspaper protest, said the commentator,

was a "deliberate and vicious intent to arouse unneceasary concern

and anxiety among relatives of prisoners of war in Japan." Closing

in the classic Soviet manner, he asserted that all this was caused

by "Japanese and American propagandists who are deliberately trying

to obstruct the work of the Soviet repatriation movement."

The paradoxical combination of a Simon-pure Commiunist Party

petition, with a nation-wide editorial campaign, gave the Soviet

Government pause.

SCAP had repeatedly pressed them for the resumption of repatriation.

Idle ships were waiting steam-up to report to Soviet ports.

Then came a shattering Soviet announcement. A "Tass" press release

in Moscow on 20 May indicated that only 95,000 former Japanese troops

remained to be repatriated.

This figure was at complete variance with official Japanese Goverhnient

Demobilization Bureau compilations and General Headquarters G-2

and G-3 Demobilization/ Repatriation Record Sections.

These records listed a total of 469,041 persons still to be repatriated

from Soviet controlled areas as of 26 May 1949.

For years, repeated efforts by SCAP to obtain precise statistical

information from Soviet Authrities on general prisoner of war totals

or deaths of Japahase internees had been abortive.

Soviet repatriation authorities had refused to allow repatriates to carry

ashes of their dead back to their homeland, an old Japendse tradition

and had suppressed the transmittal of Japanese rosters of deceased

internees to offset this official silence.

Instead Japanese authorities at home had been required to compile

death lists through exhaustive and time-consuming interviews of

returneees; under this system, Japanese internees were not officialy

listed as dead until the exact date, place and cause of death could be

a substantiated by at least two witnesses.

This Soviet failure to report deaths among Japanese prisoners held

for over four years in Siberian camps probably accounts for the wide

discrepancy between Soviet and Japanses repatriation figures.

The difference between the Soviet and Japanese figures is roughly

374,000 persons.

Though this figure appears staggering, it must be remembered that

the prisoners were held for over four years under unbelievably hard

working and living conditions conducive to an extrely high death rate.

The discrepancy between Soviet and Japanese records is glaring1y

evident, in the official tabulation as of May 1949, the beginning of

this year's repatriation season.

(See attached Table)

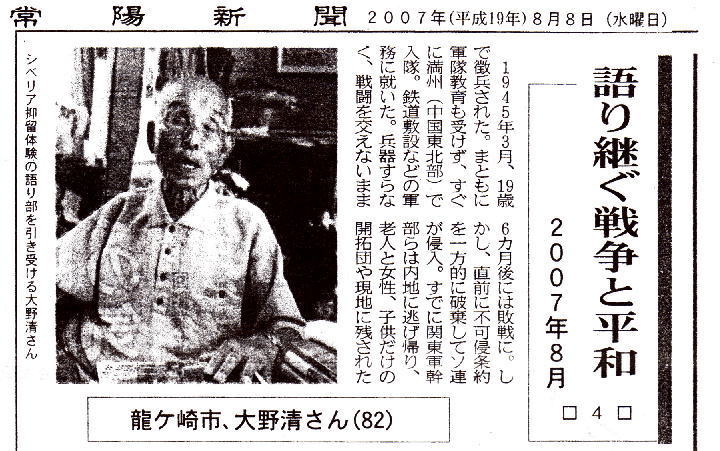

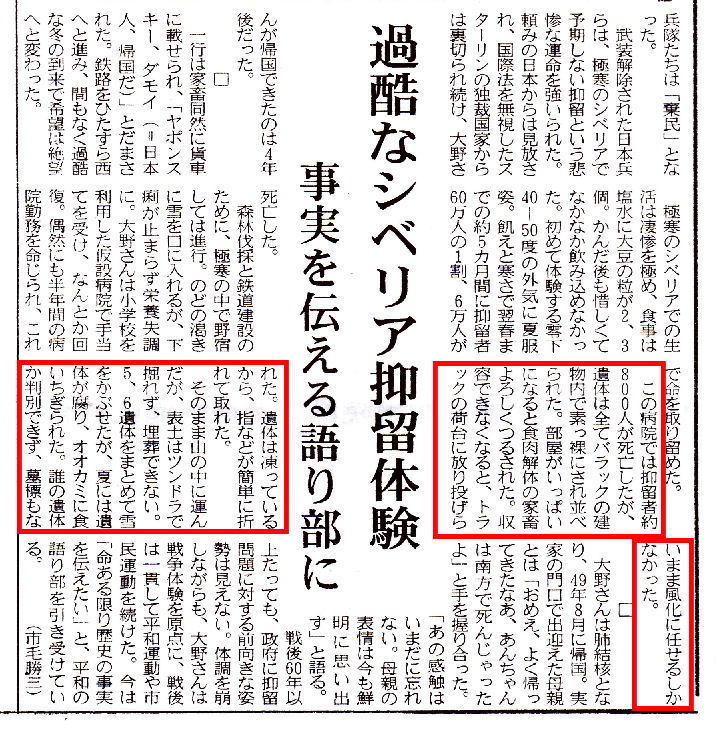

Re:シベリア抑留者数の徹底調査を

Ⅱ

The Death-Factor

in Soviet Prisoner of War Camps

Surrender of the Japanese Army in 1945 placed

under Soviet responsibility 2,723,492 Japanese

(civilian and military)

according to the Japanese General Staff.

Approximately 700,000 of these were transported

from Manchuria and Korea

into Soviet territory for internment.

As of May 1949, the repatriation account showed

469,041 military and civilian personnel

still to be repatriated and chargeable to

Soviet prisoner of war authorities.

The Soviet authorities consequently will be accountable

for 374,041 persons after deducting this season's

announced repatriation of 95,000.

The Japanese Government estimates

153,509 possibly alive,

based on the receipt of post cards by relatives

in 1947 and 1948; this is by no means conclusive,

but exceeds, under any criterion,

the official Soviet figure of 95,000 to be repatriated

as of 1 May 1949;

For many years prior to the surrender,

the Japanese Government had kept a detailed record

of the movements of military and civilian contingents.

Their official records were initially checked by G-2,

in clarge of

the Agenda for the Surrender Delegation in Manila,

in 1945,

and have been under periodic scrutiny since,

in the G-3 surveillance of the repatriation programs

and related naval transport.

The statistics have been checked

through every possible means,

including nation-wide surveys of the families

of missing personnel,

conferences with survivors of

Japanese military units disarmed by the Soviets

and the countless interrogations

of thousands of returnees from various Russian PW camps.

Repatriates report that intolerable conditions found

upon arrival at prisoner of war camps in 1945

resulted in thousands of fetalities.

A tabulated list of 125 prisoners of war camps

in the Soviet Area,

giving the number of prisoners and number of dead,

was compiled by

the Japanese Demobilization Bureau

in January 1947,

based on numerous interrogation reports,

oral and written statements

by repatriates.

Of 209,300 prisoners of war in these camps,

51,332 died from malnutrition and communicable diseases.

The mortality rate obtained was thus 24.5 percent.

This cumulative percentage deals with the first years

after the war, when prisoners treatment

and general camp conditions were admittedly at their worst.

In spite of improvements after 1947,

the cumulative death rate for the four year period

would still represent an appalling

and reckless waste of Japanese lives.

In addition to statistics

arrived at through analytical research

and compilation,

thousands of repetriates have made sworn statements

which substantiatean

excessive mortality rate

of prisoners of war,

in certain periods,

through malnutrition, overwork, cold and disease.

Said one returnee: "After the surrender,

we were disarmed at Haingan, Manchuria,

and taken to the coal mining town of Morodoi, Mongolia.

Later an epidemic broke out among us

and all the prisoners in the camp contracted it.

Only 225 prisoners out of more than 600 survived.

This constitutes a catastrophel death rate

of approximately 60 percent in this particular area.

Another one stated:

"Our battalion of 350 men was detained

in the 3rd PW Camp in Khabarovsk.

About 200 men died from illness and malnutrition,"

This, again, is a death rate of almost 60 percent.

A 1948 repatriate explained

to the widow of one of his PW comrades:

"In October 1945 we were sent to a camp west of Chite,

where we felled trees.

Owing to meager fcod rations and severe cold,

many prisoners fell ill,

and toward the end of March 1946,

50 percent of the prisoners in the camp died.

At that time your husband fell ill

with eruptive typhus.

Owing to the shortage of medicines, he died."

Another 1948 returnee said:

"Our group of about 1,000 was taken prisoner

in Menchuria when the war ended.

We were taken as far as the Ural Mountains

in European Russia, and interned in a camp.

About 70 percent were repatriated safely,

but the rest died either from malnutrition

or accidents while working.

Repatriates have expresscd extreme bitterness

concerning the camps in the Amur area,

reporting 3,000 deaths in a total of 11,000 internees

in some 20 camps,

a death rate of approximately 27 percent.

One returnee from this area reported:

"The number of dead buried

in the Kuibyshevka Special Hospital, Area No. 888,

from a count of graves, totaled 1,500.

At the hospital in Blagoveshohenak,

500 prisoners of war died of smallpox and other diseaaes;

in the Mukhino and Tu Camps, there were 600 dead;

in other camps 400 were reported;

these figures aggregate 3,000."

A repatriate employed as a grave digger

at one of the district PW hospitals reported that

"So many died from starvation and disease that

a crew of 50 men could not keep up

with the job of burying the dead.

According to a medical officer,

the deaths between 1945 and 1946

ran as high as 30 percent of the prisoners in that area."

A death rate of 30 percent,

even allowing for cumulative errors,

assumes more serious proportions

compared to the Japanese domestic death rate

at the height of the American air blitz of only 2.9 per hundred.

If we strike an average of the statistical death rates

applied to the three winters from 1945 to 1947 inclusive,

under variable camp conditions,

we arrive at a certain annual cumulative rate of 7%.

With a weeding out of the physically unfit through death,

the sturdy survivors, with greater resistance,

show a decreasing mortality rate, combined with

a factual improvement in living conditions in 1948 and 1949

for calculated political effect,

in order to support the systematic Communist indoctrination

of the remaining prisoners.

Discounting that the initial high percentages,

reported in certain localities in 1947,

apply uniformly to all camps,

the general application of these macabre percentages,

in a descending scale after the murderous winter of 1945,

will account for the discrepancy

between Soviet figure of 95,000

and Japanese totals of 374,041 prisoners of war

unaccounted for at the end of the repatriation season of 1949:

Soviet camp authorities have repeatedly refused

to answer queries into the fate of these unknown thousands.

When confronted recently with an eccounting

for the 374,000 misaing,

a Soviet spokeaman coldly brushed aside all implications

and voiced indifference to "the book-keeping methods"

of the Japanese Government or SCAP.

This is poor comfort for the thousands

of bereaved Japanese families

that have awaited thc return of a father or son.

The world will hold

the Soviet camp authorities responsible

for tolerating conditions and treatments

that have resulted in the probable death

of several hundred thousand Japanese prisoners of war,

in military and civil categories.

兵隊たちは「棄民」された。以後、

日本政府・日本外務省は、彼らを「非国民」扱い。

Ⅲ

Malnutrition and Lack of Medical Care

in Soviet PW Camps

Repatriates are unanimous in asserting that especially

during the first year of their captivity in Siberia

food supplies were far below the minimum needed

to offset cold and fatigue.

Internees were forced to rely on whatever they could scavenge

from the countryside to supplement their deficient diet,

eating bark rrun trees, frogs, snails

and anything else they could find.

Accentuated by a total lack of sanitary facilities,

disease spread through bodies already weakened by fatigue,

exposure and malnutrition.

The death rate was high in all of the prisoner groups

even before they arrived at the make-shift internment camps.

Camps reflected almost total unpreparedness

by Soviet authorities

to care for large numbers of prisoners.

Prisoners were generally housed

in whatever facilities were available,

usually in labor camps that lacked any serious provision

for sanitation or welfare.

Many camps were far from human habitation

and almost all were considered totally unfit as living quarters

because of poor construction and overcrowding.

Repatriates allege that it was not unusual for prisoners

to be herded into buildings so tightly that they could not lie dawn.

Statements bearing out these facts have bean furnished

by thousands of Japanese repatriates. One reported that

"in the camp some prisoners killed themselves, others escaped.

For fully three months we were given only potatoes,

so we ate all the frogs, snails and slugs around the camp."

Typical coazuents follows "A number of us fell ill

because of insufficient clothing

in addition to the poor food supply;

four prisoners scuetimes shared one ration;

often no food was received for an entfre day.

Quarters were crowded, facilities inadequate."

Approximately 26,000 Japanese civilians were assembled

in an area around Hamhung (Korea) in May 1946.

"Seven thousand died from exposure and starvation;"

and "we left Suifenho on 13 September 1945,

crossed the Amur River

and marched for about a month across the Siberian wilderness,

suffering from hunger, chill and fatigue.

Our destination was a camp in a mountain mining area

where neither house nor life could be seen."

All prisoners agreed that

conditions were so bad that only the strong could survive.

Sanitary conditions were so inadequate

that typhus, eruptive fever, pneumonia

and other diseases were rampant.

To a large extent

this was due to a lack of resistance

resulting from malnutrition, fatigue and exposure.

Returnees assert that the lack of facilities in the camps

to prevent the spread of disease

and the general apathy of Soviet authorities

toward the illnesses of the prisoners

often permitted the epidemics to become critical

before anything was done.

Thus many deaths, estimated at 10 percent

in even the best camps, were caused by disease.

The prisoners, in weakened condition, were easy victims,

even succumbing to diseases that are not usually fatal.

The ratio of deaths to number of prisoners was still higher

in camps in obscure localities.

Medical care was scanty and existing dispensaries

and hospitals were understaffed

and lacking in equipment and medicines.

Indeed, had it not been for medical supplies and stores

from the Japanese Army in Manchuria and Korea

and the availability of trained Japanese medical personnel,

repatriates believe that

medical assistance would have been entirely lacking.

In their attempt to get all the labor possible from prisoners,

Soviet authorities reportedly forced injured and sick prisoners

to work and these individuals were often subjected to beating

and other disciplinary action

if they were unable to complete their work satisfactorily.

Only prisoners with fever temperatures of over 100°Fahrenheit

and those with visible external injuries

were relieved from work.

Thus hernia, appendicitis, zieumonia, tuberculosis

and other illnesses often killed the prisoners

because of lack of treatment.

Individuals seeking medical attention were usually

suspected by authorities of "malingering"

and so prisoners did not seek attention

for fear of disciplinary action in the event

that nothing serious could be found.

With the start of repatriation the policy was

to repatriate only internees too ill or weak to work.

However, most of these individuals were interned

in hospitals for a time to recuperate before actual repatriation.

If their health improved markedly

they could always be returned to PW camps.

Those who did not show improvement,

however, were repatriated.

Some were so ill before entering hospitals that they died there.

Some 10/20 percent of the prisoners transferred

to hospitals in North Korea, from the USSR,

are reported to have died.

Innumerable other reports from returnees

round out a picture of abject misery

in which Japanese intcrnees found themselves obliged to exist.

Everywhere they were forced to perform heavy manual labor

while the food issued was both meager

and lacking in nourishment.

Almost everywhere housing was poor

and deficient in proper sanitary facilities.

The inevitable result of the conditions of starvation,

over-crowding and filth was that the sickness rate soared

and finally assumed epidemic proportions.

It was obvious to internees that

the Soviets had no serious plans to care for the sick.

In this period the Soviets could not control

even comparatively minor illnesses and many died who,

with a modicum of care, would have recovered.

But real tragedy befell when malignant,

filth-bred epidemics appeared.

Top killer was eruptive typhus.

Victims first developed a fever

accompanied by a mulberry-colored rash.

Next they would thrash in delfrinm,

become covered with ulcerations

and suffer severe attacks of diarrhea,

after which they would fall,

into a deep final stupor preliminary to death.

During all these stages

the possibility of contagion was great,

and the disease swept through the crowded,

filthy encampuents.

In the Chien-Tao and Yen Chi internment camps alone,

repatriates report that more than 10,000 succumbed

to the disease.

Those who lived through the typhus epidemic

faced lung diseases brought on by extreme exhaustion,

scurvy resulting from diet deficiencies,

and the occasional amputation of gangrenous toes,

fingers, arms or legs

which had been frozen in the bitter cold.

Regardless of the suffering that prisoners endured,

camp authorities forced them to produce a set amount of work.

Someone who made the trip to Siberia

in the "comparative comfort" or an open freight car

loaded with 100 of his fellow prisoners,said:

" We worked during the day only at first,

later we had to work even at night.

In the meantime rations had become very bad

and we worked on empty stomachs.

The temperature was sometimes 40 or 50 degrees

below zero.

Due to hunger and hard work, we gradually became weak

and many comrades were taken ill and died.

We ate weeds and anything we could get...."

Cumulative evidence of the incredible heartlessness

of the Soviet camp authorities toward the Japaneso

interned in Siberian prison camps

came in with every shipload of men returning from captivity.

One repatriate, a surgeon, reported that

under Soviet Army orders he established

a 1,000 patient hospital in North Korea.

He added that in June and July 1946,

the Soviets sent 30,000 serious cases and cripples

who were unable to work to North Korea

where, hampered by overcrowding and

lack of medical supplies,

both the patients and the hospital staff

went through "indescribable hardships".

The Soviet troops, the surgeon went on,

"searched the prisoners for any documents,

ashes, hair and like items in order to conceal

their atrocities and seized all evidence

by making surprise inspections".

The doctor concluded his report with the statement

that he and members of his staff managed

to evade Soviet searchers by concealing

certain documents and records in secret places.

Another repatriate, a former Japanese Army captain,

after verifying the surgeon's story,

made the following statements

"Due to unsatisfactory conditions

an unknown fever broke out

and our comrades were infected daily.

There was only one non-commissioned sanitary officer

and he had no sanitary equipment and very few medicines.

Despite our earnest entreaty,

the Soviet authorities still enforced the allotted work,

while the fever spread throughout the whole company.

Together with the fever,

all members of the company suffered malnutrition.

By this time, we were allowed to enter the hospital,

but despite the efforts of a Japanese nurse

many of our comrades died.

I carried the ashes of 25 dead with me,

but to my regret, I was obliged to bury all of them

due to the stubborn rejection of the Soviet authorities.

Moreover, a name list which I valued very much

was also confiscated by the Soviet authorities.

The total dead in my company was 80."

Another repatriate reported that

Cherenhov was one of the major coal mines in Siberia

and more than 3,000 Japanese PWs

were forced to work in the coal mines.

"We were sent via the Siberian Railway

from Mukden, Manchuria to Cherenhov,

which is west of Irkutsk on Lake Baikal."

We suffered greatly from the acute cold climate,

poor and insufficient food and bad sanitation."

The unfavorable conditions under which

prisoners of war were employed

took their inevitable toll,

"with compulsory hard labor under such bad conditions

about 1,000 died of malnutrition or eruptive typhus

during a period from December 1945 to Febrw'ry 1946."

The horrors faced by the Japanese coal mining crews

who saw one-third of their fellow prisoners die

of starvation and disease

in a period of three months

can be gained from the story of a repatriate

who was employed as a grave-digger at a PW hospital:

"They came here becauso of malnutrition.

In the winter of 1945,

many of the patients had loose bowels

and about 90 percent of the men

who contracted this sickness died.

Fifty men were on duty digging graves every night.

At first individual graves were dug

but as the death rate grew

we dug graves for two, five and 25 bodies,

but even at that

we were unable to bury them all

and they were stacked up.

Most of the soldiers that died were young;

some of them also died from the cold....

According to the medical officer,

the deaths between 1945 and 1946

ran as high as 30 percent of the prisoners

in that area."

Bearing out the statements made

by the Lake Baikal coal miner,

Kazuho Furuya wrote a letter to the "Asahi" in Tokyo:

"During our internuent in the Chinagolskaya Camp, Soviet Union,

the starvation, coldness and excessive heavy work forced on us

resulted in many victims.

Soviet soldiers would carry away the naked bodies

of the dead PWs piled up on a sled."

The Maritime Provinces also provided the customary hardship

and death for the imprisoned Japanese.

On 20 October 1945, one hundred PWs

were assigned to a camp in Manzovka

where they were employed as farmers.

Eruptive typhus broke out and became so deadly

that only 60 were returned.

At a sawmill nearby 120 out of 200 died of the fever.

A former inmate of a PWs camp in Ulan Bator,

Outer Mongolia, had this to say about his imprisonment

and his jailers:

"The fact that 15,000 Japanese prisoners of war

in Ulan Bator

fought and persecuted one another in order to live

is an unprecedented tragedy caused by the defeat.

We here forced to engage in various kinds of work

such as lumbering, quarrying, construction and coal mining.

Since 15,000 of us were detained in a town

with a population of 50,000

starvntion was a matter of course.

To make matters worse

we were forced to fulfill the "norn"

fixed under the Five Year Reconstruction Plan (of the Soviets)

and all our human rights were utterly ignored.

Ulan Bator was a town of thieves and prevaricators."

A returnee from Londoko, northwest of Khabarovsk,

reported that prisoners in his camp existed

on Kaoliang, soy-beans, salt and oil,

and that a death rate from malnutrition and pneumonia soared,

making the period from October 1945 to January 1946

"really a livig hell on earth".

A returnee from Antonovka and Santogo,

both in Siberia, remarked,

"Compared with the life of a PW ,

my present life in Japan is so easy

that I feel as if it is a dream.

The mere thought of the life I led as a prisoner

makes my blood run cold.

I wish to let my countrymen have a sight

of the prisoner's hardships and worry of those days."

"I was fortunate to get out of the region

400 miles west of Lake Baikal

where many of my comrades died one after another

due to a starvation diet, severe cold and heavy work",

admitted another returnee.

A Japanese who spent his period of imprisonment

felling trees near a small mountain village

180 miles north of Chitc, Siberia1,

bitterly recalled:

"Many Japanese died of tuberculosis and malnutrition

due to hard work and the food shortage.

Having been prepared for the worst,

that we would be forced to work to our dying day,

we often thought that

we would rather die than suffer from heavy labor any more.

Really we were envious of the dead at that time."

Repatriate interrogations are full of remarks such as:

"Whenever I recall to memory

the life I had in Siberia

a shudder runs through my frame" or

"As the food situation was bad, we suffered acutely from hunger."

But this comment from a repatriate

formerly imprisoned near Vladivostok

is an important clue to one of the real problems facing PWs:

"In this camp there were many democrats and communists,

however, most of them were false progressives.

The living conditions were not so good,

but we were especially annoyed

by the. Japanese who acted as informers."

To the miseries of starvation, bitter cold

and hard labor burdening the PWs,

the Soviets added their indoctrination plan

which was furthered

by self-seeking stooges

recruited from among the PW ranks.

One disgusted returnee reported that,

"at the time of my repatriation

the 'Democratic League' was organized

and the greater part of its members

consisted of former military personnel

and civilian workers.

The league was conducting

a communist training course

and had great power

in deciding who was to be repatriated."

One of the leaders of the Youth Communist Party

formed by the PWs said:

"I was one of the leaders

of the Youth Communist Party

during my detention in the Soviet Union.

Prior to cur embarkation for Japan at Nakhodka

I, like other conrades, hailed

" Long live Generalissimo Stalin !"

and pledged before the Democratic Group

to join the Japan Communist Party

as soon as we landed in the country of the reactionaries.

After I returned home I learned

that the Occupation Forces,

which we were told to be our greatest enemy

were exerting the utmost effort

to accelerate our repatriation

and the people at home,

whom we believed to be indifferent towards our return,

were making a strong campaign to expedite our repatriation.

I was surprised at the real situation of the country

and became aware

that the ideas

with which we were indoctrinated were false."

Re:固く閉ざされたパンドラの箱-シベリア抑留の事実隠蔽

IV

Soviet Exploitation

of Japanese Prisoner of War Labor

The Soviet policy to exploit prisoners of war to the fullest

before repatriating them resulted in a heavy toll of lives.

The Soviet Union's primary interest

with respect to Japanese PWs

was the complete utilization of manpower and technicians

in various fields of industry

to increase their postwar economic-military potentials.

More labor, more production,

were the Soviets' unceasing demands

to attain their avowed goal of overtaking

and surpassing the capitalistic world

in agricultural and industrial production

by a series of Five Year Plans.

To this end, Japanese internees

were compelled to engage in extremely arduous labor

with pitifully inadequate food, clothing and shelter.

On arrival at Soviet PW camps,

internees were immediately forced to work

on the projects

for which that particular camp was responsible.

Exceedingly perfunctory medical inspections wore given

by Soviet medical personnel

to determine the work capacity of individual prisoners.

Physical classifications varied at different camps.

The main distinction was

between those capable of performing heavy labor

and those fit only for light duties.

In many instances,

no attempt was made to follow these classifications,

and prisoners were forced to perform heavy labor

regardless of condition.

Physical examinations consisted

of the PWs stripping to their waists

and the doctors cursorily glancing at their general physical structure.

Very little attempt was made

to diagnose for internal disorder or other chronic ailments.

If a person appeared to be healthy,

he was automatically classified

as fit for heavy labor.

Only PWs with fever of over 100°were considered ill.

In case of injury, when external change was not apparent,

the injured were not hospitalized

but were put to work.

External injury without accompanying increase in temperature

was often not considered as an excuse from labor.

Work projects for manual laborers, according to ropatriates,

included lumbering, loading and unloading railcars, mining,

road or railroad repair and construction, excavation, stovedoring

and other labor requiring heavy physical exertion.

Japanese Pws, noted for their industry,

were driven to the point of emaciation

and complte fatigue.

All projects were placed

under the "norm" basis of production quotas,

which were usually much higher

than those assigned to Russian labor groups.

These "norms" were reportedly based

on the number of individuals in each labor group

regardless of physical condition.

Thus strong prisoners usually had to do much more

than their individual quotas in order to make up

for the weaker prisoners.

If the daily production of a group was

below the demands of the Soviet authorities,

the prisoners were often forced to work continuously

as long as 18 hours or more.

Regardless of weather or individual physical condition,

the prisoner' a minimum working day was eight hours.

Very rarely were the prisoners able to complete

their "norm" in such a short time.

Repatriatos report that food supplies wore so inadequate

that, combined with enforced labor and long hours,

all of the prisoners suffered from malnutrition.

Tho amount of food allotted to tho prisoners

was contingent upon the percentage of the "norm" accomplished,

and thus already enervated prisoners

who could not complete their "norm"

were further weakened

when food was denied thern.

Only in the most extreme cases of malnutrition

were prisoners relieved from work,

and it is reported that many of these subsequently died.

Othor deaths were reportedly caused by

exposure or fatigue

during working hours as a result of inadequate clothing;

and lack of rest.

Although all were in weakened condition

which became progressively worse,

the work "norms" wore not lesse

With the beginning of 1948,

many ropatriates have reported,

the Soviets began to treat Japanese PWs more kindly.

Although Soviet labor commanders were reportedly prohibited

from boating prisoners of war

to gain more production,

other means just as effective wero used to increase the PWs output.

Production races were held between camps,

with the "winning" camp receiving flattering panegyrics,

and the losing camps being looked upon with cold contempt.

Campaigns for 120 percent production or l50 percent productions, etc,

were held, with outstanding work being rewarded

by presentation of medals and banners,

and perhaps rocognition being given

in the propaganda newspaper "Nippon Shimbun".

Leaders of campaigns reached a point of frenzied enthusiasm,

with the result that PWs were often forced to work

for 12 or 13 hours a day to complete the daily work quota.

At the same time, the rumor became prevalent

that repatriation depended somewhat upon the labor records

attained by individuals and camps.

With the rising stabilization of Soviet economy in early 1948,

the pay system was added as a further incentive for labor.

PWs completing more_than_100_percent of their daily quota

were awarded food or money.

Most of this money was reported to have been "subtracted"

as "expenses" by the Soviet authorities.

Through this subterfuge the Soviets now claim that

PWs were not engaged in enforced labor,

but rather were paid for their work.

The Russians' insatiable demand for labor production

was abetted by highly indoctrinated Japanese fanatics

who were without regard for their hapless comrades.

According to repatriate, a Soviet physician found

that an internee he was treating for a leg injury

in the Rybstroy PW Camp in April 19h9,

was not feverish and placed him on full duty status.

The pain-wracked PW lagged in his work

and his Japanese foreman denounced him.

He was prosecuted for his "undemocratic" attitude

by the People's Court and was told

that his case would receive further consideration at another court.

That night, scorned by his comrades

and fearful of the future,

the injured PW hanged himself with his leggings.

This man and countless other thousands

paid the cost

of completing the current Soviet Five Year Plan

in four years.

The End

Re:日本人捕虜のシベリア奴隷労働被害

Re:

シベリア不法虐待抑留犠牲者の慰霊を

-犠牲者の慰霊なくして北方領土問題の解決はあり得ない