| Stories About Japan 日本を語る |

"Foreigners Who

Changed Japan" Series, Part 2

日本を変えた外国人 II

| Luis Frois | Philipp Franz von Siebold | Townsend Harris |

|

| Engelbert Kaempfer | Ranald MacDonald | Guido Verbeck |

|

No. 3

|

Luis

Polycarp Frois could very well be called Japan's first foreign-born

historian, having come to the country in 1563 at the age of 27 and

staying for 31 years, 20 of which were spent on Kyushu. During these

years, he objectively and extensively chronicled 16th-century Japanese

life in some 140 letters and nearly 2,500 pages of history, which later

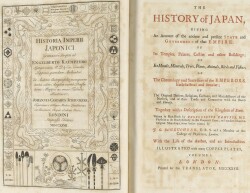

became a five-volume work called the Historia

de Japam

(History of Japan 1549-1593), and could be considered the very first

Western historiographer of Japan. Unbelievably, his work would not be

read by the greater world then as it was not published nor translated

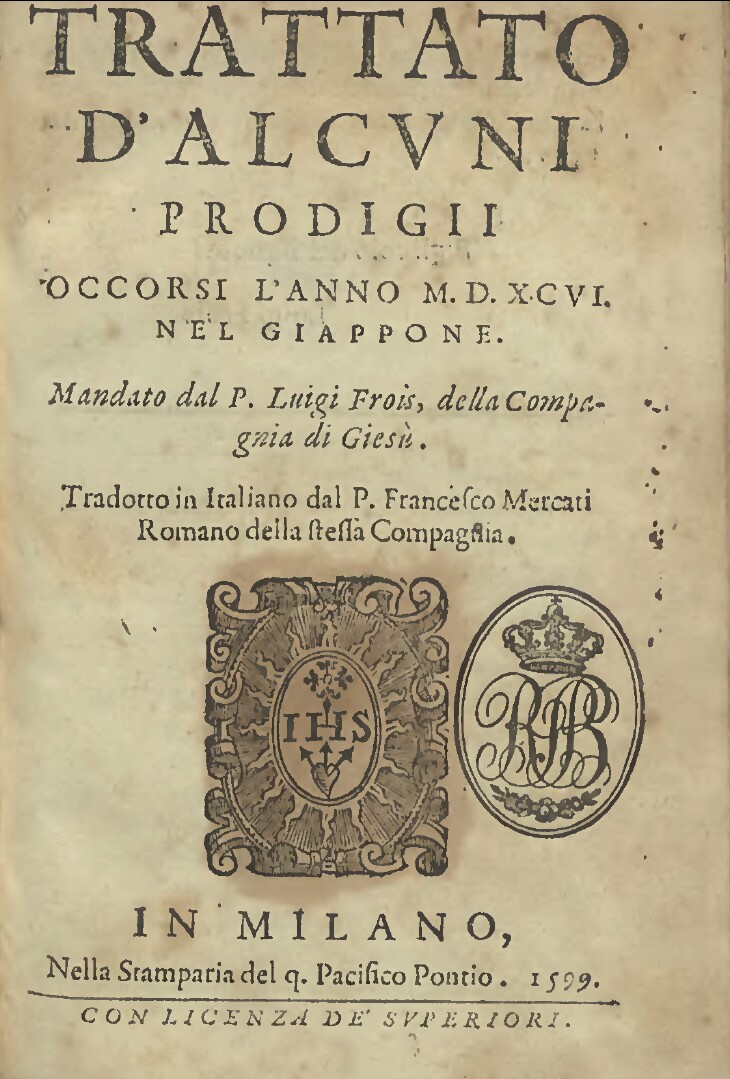

into any other language until 1976. His other interesting work on

things Japanese, the Treaty on Contradictions, was not printed until

400 years later as well. Truly odd, but perhaps the victim of internal

affairs among the more elite Jesuit leadership in Japan, specifically

the Italian Alessandro Valignano, who had a too-critical view of what

Frois had written. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the period of

Frois' writings about Japan coincided with the great increase of

commerce and intellectual exchange during the Azuchi-Momoyama era. There

had been other accounts written earlier about Japan, e.g. by Tomé Pires

in 1513; Mendes Pinto in his journal, the Peregrinação (1614); and

Jorge Alvares, who gave Francis Xavier descriptions of the Japanese

land and people in 1548. But none of these reached the depth and volume

that Frois had chronicled, nor did they have such close contact with

the great leaders of that age, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Earlier writers had had great influence on helping to bring knowledge

of Japan to the early Portuguese explorers of Asia who, as a result,

gradually brought western culture to the Japanese. Later writings by

Japanophiles Gaspar Vilela, Luis Almeida, and João Rodrigues had even

more influence on making Japan known to the world, and the world known

to Japan. Through these early contacts with the West, Japan's future

would be changed in amazing ways. There

had been other accounts written earlier about Japan, e.g. by Tomé Pires

in 1513; Mendes Pinto in his journal, the Peregrinação (1614); and

Jorge Alvares, who gave Francis Xavier descriptions of the Japanese

land and people in 1548. But none of these reached the depth and volume

that Frois had chronicled, nor did they have such close contact with

the great leaders of that age, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Earlier writers had had great influence on helping to bring knowledge

of Japan to the early Portuguese explorers of Asia who, as a result,

gradually brought western culture to the Japanese. Later writings by

Japanophiles Gaspar Vilela, Luis Almeida, and João Rodrigues had even

more influence on making Japan known to the world, and the world known

to Japan. Through these early contacts with the West, Japan's future

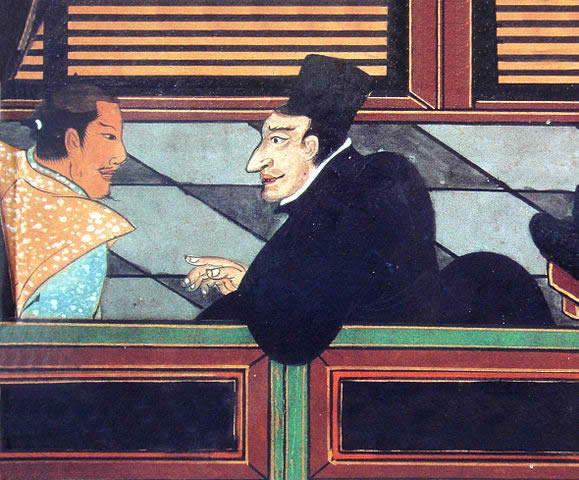

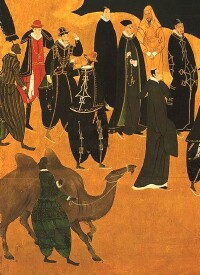

would be changed in amazing ways.Frois spent his first year and a half in Hirado and nearby Takashima, learning the Japanese language and culture. Over the next four years, he was then sent to Kyoto, then to Sakai, then back to Kyoto, where he became the first Jesuit to reside there. Among the highlights of Frois' seven years in Kyoto were the high-level meetings with Nobunaga, talking with the leader about a variety of things both Japanese and European. Nobunaga was especially fond of Frois and very interested in all the new  things brought over by the

Portuguese, even wearing

clothing that the nanbanjin would wear. In an official parade in Kyoto,

Nobunaga sat on a velvet chair that the Jesuit missionary Valignano had

given him, an immensely practical device never before seen in Japan.

Frois even showed Nobunaga an alarm clock, but the latter did not wish

to keep it as it would seem too difficult to regulate. Frois is said to

have

served as a sort of diplomat for Nobunaga, receiving letters from the

ruler that allowed the Jesuit's religion to be promulgated in Kyoto and

even a seminary to be built in Azuchi. Frois would ten years later meet

with Hideyoshi and act as interpreter in a very important meeting with

other Portuguese leaders, and be given a special tour of the new Osaka

castle. things brought over by the

Portuguese, even wearing

clothing that the nanbanjin would wear. In an official parade in Kyoto,

Nobunaga sat on a velvet chair that the Jesuit missionary Valignano had

given him, an immensely practical device never before seen in Japan.

Frois even showed Nobunaga an alarm clock, but the latter did not wish

to keep it as it would seem too difficult to regulate. Frois is said to

have

served as a sort of diplomat for Nobunaga, receiving letters from the

ruler that allowed the Jesuit's religion to be promulgated in Kyoto and

even a seminary to be built in Azuchi. Frois would ten years later meet

with Hideyoshi and act as interpreter in a very important meeting with

other Portuguese leaders, and be given a special tour of the new Osaka

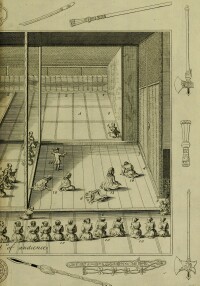

castle.As for religion, Frois and Nobunaga were both in agreement regarding Buddhism, viewing that religion with great disdain. The Nichiren bonze, Nichijo Shonin, had succeeded in having an Imperial Edict enacted in 1568 that ordered Frois be executed and his religion vanquished from Japan. Nobunaga, however, overruled the edict. Nobunaga would later carry out a massive destruction campaign against the temples and bonzes at Mt. Hiei in Kyoto. Incidentally, Frois was at his church only a block away from the place where Nobunaga burned to death on June 21, 1582, remarking, "this man, who made everyone tremble not only at the sound of his voice but even at the mention of his name, there did not remain even a small hair which was not reduced to dust and ashes."  One of the interesting episodes with Nobunaga was when Frois visited Kyoto in 1581 along with Valignano, who had brought along a Mozambican teenager to present to Nobunaga. The Kyotoans had never seen a black person before and created quite a riot just to catch a glimpse of him. Nobunaga himself was so amazed that he had the young man stripped and bathed to actually determine whether his skin color was real! This African became Nobunaga's samurai attendant and was given the name Yasuke.  Another famous individual Frois met was Sen-no-Rikyu,

renowned master of the tea ceremony (wabi-cha,

called suki

by the Jesuits) and special advisor to Nobunaga, later ordered by

Hideyoshi to commit suicide. It was through Sen-no-Rikyu that Frois was

able to ask Nobunaga for religious freedom for the Jesuits. Frois would

enjoy having tea with Nobunaga on different occasions, even showing

Frois his "golden tearoom." Incidentally, the ceramics boom in the

Arita and Imari areas of Kyushu could very well be related to the

influx of European influence and interest in Sen-no-Rikyu's tea

ceremony. So important was this ceremony that the Jesuit missionaries

created special reception rooms in their homes for this purpose, and

Japanese would engrave teacups with European symbols, including the

cross. "Imari porcelain" would later become a prime export to Europe

and the Middle East via Nagasaki. Another famous individual Frois met was Sen-no-Rikyu,

renowned master of the tea ceremony (wabi-cha,

called suki

by the Jesuits) and special advisor to Nobunaga, later ordered by

Hideyoshi to commit suicide. It was through Sen-no-Rikyu that Frois was

able to ask Nobunaga for religious freedom for the Jesuits. Frois would

enjoy having tea with Nobunaga on different occasions, even showing

Frois his "golden tearoom." Incidentally, the ceramics boom in the

Arita and Imari areas of Kyushu could very well be related to the

influx of European influence and interest in Sen-no-Rikyu's tea

ceremony. So important was this ceremony that the Jesuit missionaries

created special reception rooms in their homes for this purpose, and

Japanese would engrave teacups with European symbols, including the

cross. "Imari porcelain" would later become a prime export to Europe

and the Middle East via Nagasaki.Perhaps the most important of events recorded by Frois was the journey of four Japanese samurai teenagers to Europe in 1582. Called the Tensho Embassy, it was initiated by Valignano and sent by very important daimyo in southern Japan. These youth were probably the first Japanese group to ever visit Europe. Their travels lasted eight years (only two of which were actually spent in Europe) during which they visited famous places and met important people such as King Phillip II of Spain and the popes of Rome. The young men brought back to Japan many different items, including books,  musical instruments, a modern

atlas and a

globe, no doubt having a great impact on Japanese scholars, and

especially Hideyoshi. Frois wrote that Hideyoshi enjoyed the classical

music played by these young men on the harpsichord, harp, violin and

lute so much that he asked them to repeat their performance three times! musical instruments, a modern

atlas and a

globe, no doubt having a great impact on Japanese scholars, and

especially Hideyoshi. Frois wrote that Hideyoshi enjoyed the classical

music played by these young men on the harpsichord, harp, violin and

lute so much that he asked them to repeat their performance three times!Valignano had wanted these young scholars and their attendants to learn printing techniques in Europe, which they did, and brought back with them the greatest and most important piece of equipment in their cargo, the printing press, the first the Japanese had ever seen. They had also brought kanji and kana metal dies to use in the press, and the first print shop was set up in Kazusa in Shimabara. Through this amazing invention, the Japanese were introduced to the first Japanese-Portuguese language books, namely João Rodrigues' book of grammar and later a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary, called "a masterpiece of its kind." The grammar book alone was remarkable in that it recorded the actual phonetic spelling of Japanese vocabulary, helping us to know how Japanese words were pronounced in the 16th and 17th centuries. Rodrigues, incidentally, became the chief translator for Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, but was later replaced by the Englishman, William Adams.  There

were many other European ideas that affected Japanese culture. Perhaps

the greatest was education, as a number of schools and colleges were

built by the Portuguese. One estimate has it that there were some

12,000 pupils at these schools in western Japan who were being taught

about western civilization and thought. With all the foreign teachers

in the schools as well as Portuguese merchants and missionaries in the

country, it is no wonder that so many foreign words became a part of

the Japanese language – one researcher said they had imported around

4,000 words, though many later became obsolete. Conversely, the

Portuguese adopted Japanese words into their vocabulary which are still

in use today. There

were many other European ideas that affected Japanese culture. Perhaps

the greatest was education, as a number of schools and colleges were

built by the Portuguese. One estimate has it that there were some

12,000 pupils at these schools in western Japan who were being taught

about western civilization and thought. With all the foreign teachers

in the schools as well as Portuguese merchants and missionaries in the

country, it is no wonder that so many foreign words became a part of

the Japanese language – one researcher said they had imported around

4,000 words, though many later became obsolete. Conversely, the

Portuguese adopted Japanese words into their vocabulary which are still

in use today.Another idea was city-building – construction design and techniques that were utilized in building schools, hospitals and churches for the Europeans, seen especially in the city of Nagasaki. Prior to Nagasaki, ports in Kagoshima, Oita, Hirado (a famous whaling and pirate port), Yokoseura (where Frois first arrived in Japan, in north Saikai, becoming the model city upon which Nagasaki was based) and Fukuda had been used by trading ships. Fukuda was where the daimyo, Omura Sumitada, had recommended the Jesuits locate after Yokoseura had been destroyed (due to the bitterness of the Hirado daimyo over loss of trade profits). However, the port was not in a safe location. Frois writes about how a priest, Belchior de Figueiredo, searched for another harbor by sounding various inlets. He soon found that Nagasaki, just to the east of Fukuda, was an ideal spot for ships to enter for trade. The Jesuits gradually populated the area and a city was built, soon becoming very prosperous and the only international port for all of Japan. After a crack-down on Jesuit activity, an isolation area for them was built and was called Dejima, populated entirely by Portuguese. When they were ordered out of the country in 1639, the Dutch from Hirado took over and became the sole trading link with Europe for over 200 years. Since Frois' works were translated, his descriptions of various cities, castles and gardens throughout Japan have excited the interest of quite a number of Japanese researchers seeking more information about how exactly these sites were constructed. Even today these descriptions have created quite an interest in learning about the past. In the visitor's center in Gifu, there was a 3-D model of Nobunaga's palace, based wholly upon Frois' description of that building. Castle-building was also influenced by Europeans, probably through the many question-and-answer sessions the daimyo and great military leaders had with the foreigners. Not only was Frois greatly impressed with Nobunaga's Azuchi and Gifu Castles, he was equally amazed by the hundreds of thousands of workers involved in building the grand walls surrounding Hideyoshi's Osaka Castle. Some of the stones were so huge that it required over 200,000 men to carry them! Frois was also astonished at how clean the palaces and large houses were in Osaka. Though Frois did not interact with Hideyoshi much, he did refer to him as the second "great unifier of Japan."  Trade with Europe brought in many other new

things to Japan: Trade with Europe brought in many other new

things to Japan:

SOURCES: The First European Description of Japan, 1585: A Critical English-Language Edition of Striking Contrasts in the Customs of Europe and Japan by Luis Frois, S.J. by Danford, Gill and Reff (2014) Luis Frois: First Western Accounts of Japans Gardens, Cities and Landscapes by Cristina Castel-Branco and Guida Carvalho (2020) They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543-1640 by Michael Cooper (1965) Luis Frois History in 12 Volumes (2000) ル イス・フロイス日本史 の検索結果 Text ©2022 Wes Injerd

|

|

No. 4

|

|

No. 5

|

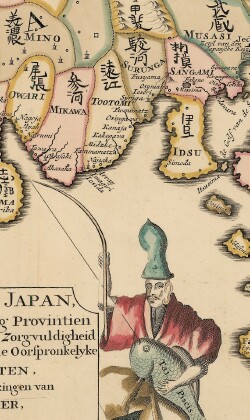

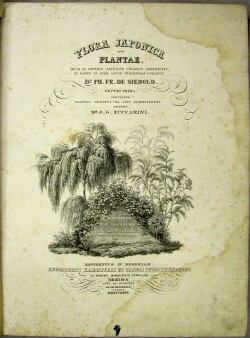

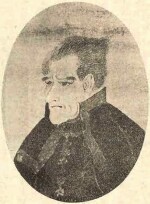

| Philipp Franz

von Siebold was born in Wurzburg, Germany, on Feb. 17, 1796. He was

chief physician at Dejima, Nagasaki, from 1823 to 1829, and later

became adviser to the Dutch Trading Society from 1859 to 1861. Though Chinese medicine had been known in Japan for hundreds of years, and the work of German and Dutch doctors such as his predecessors Thunberg and Kaempfer in the 18th and 19th centuries, Siebold is best known as the German who brought Western science and medicine to Japan. He was 29 years old when he arrived in Dejima on August 11, 1823, appointed to be the official physician for the Dutch East India Company. This office also included the job of scientist, or in the case of Siebold, botanist, which allowed him to do a very large amount of research, basically learning as much as he could about Japan. Next to Kaempfer, Siebold stands as the most voluminous writer of things Japanese, especially in regards to things natural. It has been remarked that Perry would have had Siebold's works added to his library were they not so exorbitantly priced! There is perhaps no other 19th-century writer on things Japanese that has been so widely quoted as Siebold -- even more so, no other foreign personality in Japan has had so many books written about him, "882 western and 740 Japanese titles" (per Philipp Franz von Siebold and His Era: Prerequisites, Developments, Consequences and Perspectives (2000), p95). Once becoming the official physician in Dejima, his reputation grew immensely and dozens of doctors from all over Japan came to him for advice, especially regarding surgical methods, in which Siebold excelled above his predecessors.  He was allowed to even treat patients outside of Dejima, but the number

grew so large that a house was built for him in an area called

Narutaki, where later he established a medical school. One of Siebold's

most-promising students was a man by the name of Choei Takano. After

graduation, Takano stayed in Nagasaki to help Siebold translate

Japanese medical books into Dutch, and then later translate Dutch books

into Japanese, which was of immense benefit to many. Perhaps Siebold's

most important medical advancement in Japan was the introduction of the

vaccine, resulting in numerous Japanese being inoculated against

smallpox around the year 1823.

He was allowed to even treat patients outside of Dejima, but the number

grew so large that a house was built for him in an area called

Narutaki, where later he established a medical school. One of Siebold's

most-promising students was a man by the name of Choei Takano. After

graduation, Takano stayed in Nagasaki to help Siebold translate

Japanese medical books into Dutch, and then later translate Dutch books

into Japanese, which was of immense benefit to many. Perhaps Siebold's

most important medical advancement in Japan was the introduction of the

vaccine, resulting in numerous Japanese being inoculated against

smallpox around the year 1823.Though he was an expert in his field, he could not relate his knowledge to the Japanese without the help of Japanese interpreters. Much of his success was no doubt due to these interpreters who were able to bridge the gap, not only in conveying what Siebold had to teach, but in explaining what the Japanese themselves desired to teach him about their land, culture, language, politics, and lifestyle. Through this exchange, Siebold could write authoritatively about Japan and her people. Unfortunately, much of what he had intended to send to Europe as museum pieces of his studies was confiscated during the "Siebold Incident" of 1828. However, when he left Japan the second time, he brought with him an immense number of items, including his own personal library of over 3,400 volumes, which are all now at the Leiden University Library in the Netherlands.  Around

1823 Siebold met and "married" a 16-year-old geisha (aka "Oranda-yuki")

named Sonogi. Her real name was Taki Kusumoto (called Otakusa by

Siebold), and she became the first practicing woman physician in Japan,

even serving the Meiji Empress in 1882. The Siebolds had a daughter

named Ine Kusumoto (born 1827), who became the first woman doctor in

Japan educated in Western medicine. Around

1823 Siebold met and "married" a 16-year-old geisha (aka "Oranda-yuki")

named Sonogi. Her real name was Taki Kusumoto (called Otakusa by

Siebold), and she became the first practicing woman physician in Japan,

even serving the Meiji Empress in 1882. The Siebolds had a daughter

named Ine Kusumoto (born 1827), who became the first woman doctor in

Japan educated in Western medicine.In 1826, Siebold joined the official Dutch journey to Edo to pay homage to the Tokugawa shogun, Ienari. Siebold was able to not only meet the shogun, but also some very important Japanese scientists, including the shogun's physician, Hoken Katsuragawa, and astronomer,  Kageyasu Takahashi. Interestingly, William Griffis in his 1895 book

about Townsend Harris, wrote concerning Siebold, "In 1826 P. F. von

Siebold accompanied the Dutch to Yedo, where, after his companions

left, he remained until January 18, 1830, most of the time in prison."

Kageyasu Takahashi. Interestingly, William Griffis in his 1895 book

about Townsend Harris, wrote concerning Siebold, "In 1826 P. F. von

Siebold accompanied the Dutch to Yedo, where, after his companions

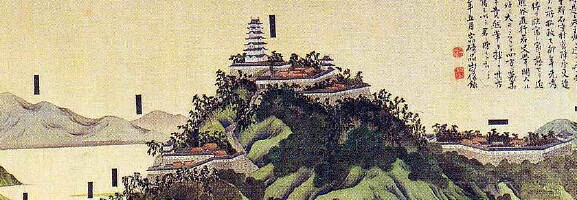

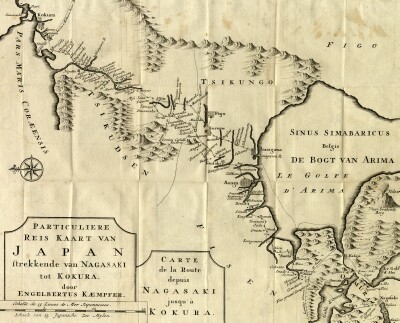

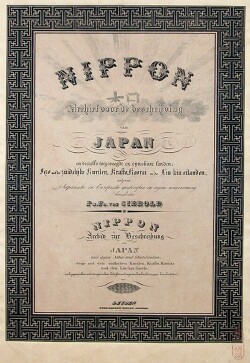

left, he remained until January 18, 1830, most of the time in prison."Siebold stayed in Japan until October 22, 1829, when he was expelled for attempting to smuggle out maps of Japan, including very detailed survey maps produced by the reknowned Tadataka Ino (see this western Japan portion of the map). While back in Europe, Siebold worked on his collections as well as his famous works: Nippon, Fauna Japonica, Bibliotheca Japonica, and Flora Japonica. In 1845, he built a villa with a greenhouse and named it, "Nippon." After he married Helene, the following year his son, Alexander, was born, the first of five children. Siebold continued to have a desire of returning to Japan, which he missed greatly. He was especially interested in the Perry expedition to Japan of 1852-1853: "That it will be successful by peaceful means I doubt very much. If I could only inspire Commodore Perry, he would triumph." Siebold requested that he join the expedition, that he alone had "a plan to open the Japanese Empire to the world." Perry, however, denied the request due to Siebold's "banished person" status in Japan. Siebold was so irritated at being rejected that he wrote a pamphlet that basically thanked the Russians for opening up Japan! There was some suspicion that Siebold wanted the Russian fleet, which sailed into Nagasaki a month after Perry's ships had entered Edo, to take the credit for opening up Japan to the world. Of special note in Siebold's request was the desire that America "not trouble  herself

about the present religion and politics of Japan," i.e. do not excite

distrust in Japan by sending over missionaries. The Russians were not,

incidentally, warned by Siebold to avoid the mention of Christianity to

the Japanese. None of the objections Siebold had said the Japanese

would use to stall negotiations ever came true. Very interestingly,

Perry suspected Siebold of being a Russian spy! herself

about the present religion and politics of Japan," i.e. do not excite

distrust in Japan by sending over missionaries. The Russians were not,

incidentally, warned by Siebold to avoid the mention of Christianity to

the Japanese. None of the objections Siebold had said the Japanese

would use to stall negotiations ever came true. Very interestingly,

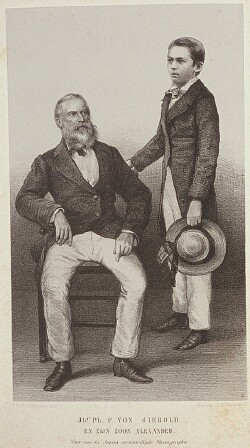

Perry suspected Siebold of being a Russian spy!Siebold's dream did come true and he was allowed back to Japan in 1859 (accompanied by his son, Alexander) as an adviser to the Dutch Trading Society in Nagasaki. However, he was made to leave again in 1862, having attempted to become an international political adviser to the Bakumatsu leaders of Japan in Edo (Tokyo). Tenacious and stubborn as  he was, Siebold then asked

the Dutch

government to send him to Japan, then the Russian, and finally the

French. All requests were denied. During his time in Japan, though, he

was able to reunite with his Japanese wife, Taki, and daughter, Ine,

and even meet Ine's 7-year-old girl, Taka. Before he left Japan in 1862

for the last time, he gave his house and garden in Narutaki to Ine. he was, Siebold then asked

the Dutch

government to send him to Japan, then the Russian, and finally the

French. All requests were denied. During his time in Japan, though, he

was able to reunite with his Japanese wife, Taki, and daughter, Ine,

and even meet Ine's 7-year-old girl, Taka. Before he left Japan in 1862

for the last time, he gave his house and garden in Narutaki to Ine.Due to the influence of Siebold's work, German medical education, and hence German terminology, has remained the basis of medical literature in Japan, up to the mid-20th century. Japan also followed the German system of schooling children, and even the army and how it was organized. Botany was especially indebted to Siebold's labors, having brought tea seeds to Batavia, Java, and many other plants to the Netherlands and from there to Europe. In all, Siebold had collected some 14,000 Japanese botanical and 7,000 zoological specimens. Siebold died in Munich on Oct. 18, 1866, at the age of 70. At the time, he was working on forming a French-Japanese trading company that would give him the opportunity to once again return to Japan, to the land and the people that had meant so much to him.

LINKS: Siebold Museum (Wurzburg, Germany) Japan Museum SieboldHuis (Leiden, the Netherlands) Siebold Museum (Nagasaki) SOURCES: Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan, 1793-1841 by Keene (2006) Philipp Franz von Siebold and His Era: Prerequisites, Developments, Consequences and Perspectives (2000) The Remarkable P. F. B. Von Siebold: His Life In Europe and Japan by Compton and Thijsse (2013) Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron under Perry Vol2 (1856) |

|

|

No. 6

|

| NOTE: Was Ranald

the first English teacher in Japan? It would seem that

the English, e.g. William

Adams, John Saris, and Richard Cocks, who were in Hirado, would

have been used in some capacity to teach the English language to the

Japanese, but nothing concrete has been written in that regard. It

would, therefore, be fair to say that Ranald was the first "full-time

English instructor," his sole existence in Japan during his short stay

being taken up with educating those few key Japanese interpreters in

proper English usage, who in turn would be influential in the

modernization of Japan. Ranald MacDonald was born in 1824 in what was once the British Territory of Northwest America, in a city now known as Astoria, Oregon. His father was from Scotland and was serving as chief trader in the British Hudson's Bay Company in that area over which it had a trade monopoly. Ranald's mother was a Chinook Indian, "Princess Sunday," the daughter of a famous tribal chief -- for which Ranald would be labeled as a "half breed," the son of a "squaw man." Yet it was this very background that brought him to think about his roots, and the connection with three shipwrecked Japanese about whom he would later hear about, and perhaps even meet, and influence him to embark on his amazing journey to the land of Japan.  Ranald had probably

learned much about various countries, including

Japan, and perhaps had heard stories about Kaempfer and Siebold and

Golovnin, or even actually read what they had written about Japan and

its culture. Though Ranald had traveled to many countries in the world,

one thing is for certain -- no other country had such an impact on his

life as the empire of Japan. Ranald had probably

learned much about various countries, including

Japan, and perhaps had heard stories about Kaempfer and Siebold and

Golovnin, or even actually read what they had written about Japan and

its culture. Though Ranald had traveled to many countries in the world,

one thing is for certain -- no other country had such an impact on his

life as the empire of Japan.The three Japanese who were shipwrecked along the coast of Washington State in May 1834 have created quite a stir of imagination in the minds of many who have studied about MacDonald. Their names were Otokichi, Iwakichi, and Kyukichi, and they are known for their travels around the world after their time in the Northwest, being among the first Japanese to visit London. Other than their meeting with the "Father of Oregon," John McLoughlin, at Fort Vancouver (in now Washington State), one of the most interesting activities in which they were involved was helping the German missionary in Macau, Dr. Gutzlaff, translate portions of the Holy Bible into Japanese. They did not actually meet the then 10-year-old Ranald and talk with him about Japan, or, as some have thought, plant in his mind the eventual desire to visit that country, for Ranald had already left Fort Vancouver by the time the young Japanese boys arrived. No doubt, though, Ranald had heard about them. He later wrote that he believed Japan was the "land of his ancestors," perhaps due to his time in Japan and his resemblance to her people. What definitely influenced Ranald were stories from sailors who had actually been on ships that had attempted to open up Japan. Some were even allowed on shore, but were soon made to return to their ships, without incident. Ranald had heard these stories while he was in Hawaii (Lahaina, Maui), having gone there in 1846 to look for a whaling ship bound for the Japanese islands. There were also stories about shipwrecked Japanese who had come to Hawaii that Ranald had read or heard about -- all of this exciting in him the desire to  travel to

Japan. He was so resolved in learning more about the Japanese and

instruct them on the ways of Americans that he embarked on an

incredible journey to the land of the

rising sun.

travel to

Japan. He was so resolved in learning more about the Japanese and

instruct them on the ways of Americans that he embarked on an

incredible journey to the land of the

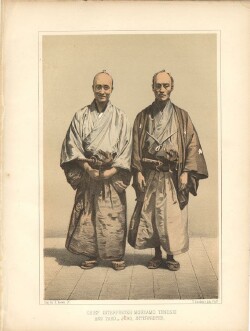

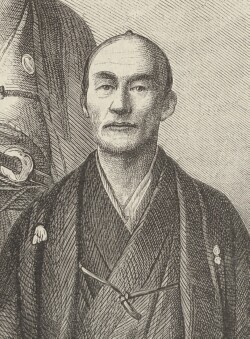

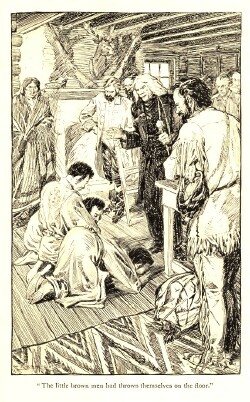

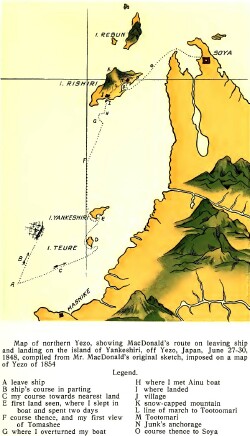

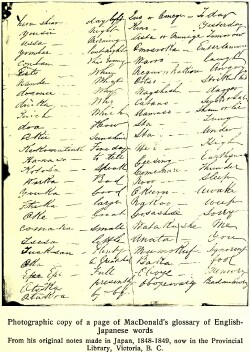

rising sun.That one driving desire of his -- to become "an instructor on history, geography, commerce, and modern art, and the Bible," and to be employed by the Japanese "as a teacher" -- actually did come to pass. Great was his wish to learn the Japanese language and serve as an interpreter when the country finally opened up to the world, and to help the Japanese become a modern country. At the age of 24, Ranald first arrived on the island of Yagishiri on the western shores of Hokkaido on June 27, 1848, then a few days later arrived on Rishiri Island on July 2 where he was "rescued" by a group of Ainu, the very first people he was to meet in Japan. From day one, he started learning to communicate with the Japanese leaders on the island, writing down a vocabulary list to help him learn the language. After spending a short time there, he was sent to Soya (near Wakkanai), and then on to Matsumae (west of Hakodate). Finally he was sent down to Nagasaki, the only district were foreigners were alllowed to live, arriving on Oct. 11, 1848. It could very well be said that his coming stirred the hearts of many, for there was a great need for English-speakers who could be used to help Japanese interpreters speak in the English tongue. Ranald was kept in a sort of prison while in Nagasaki but was treated very well there, probably because of his importance to the Japanese interpreters as a native speaker of English. Another reason perhaps was him being part Chinook, his facial features aiding him in receiving less harsh treatment by his Japanese captors as would a Caucasian. In fact, when he arrived in Matsumae, the governor exclaimed upon meeting him, "Ah, Nipponjin!" -- "Oh, a Japanese!"  Ranald was in Nagasaki

for only six months, during which time he was

utilized as an English instructor. A total of 14 students learned from

him, one of whom was Einosuke Moriyama, who became the chief

interpreter during negotiations with the Perry expedition in 1854, as

well as for the first American consul to Japan, Townsend Harris.

Moriyama's expertise was further utilized during Japan's first official

mission to Europe. Others among Ranald's students also helped influence

the future of Japan on the international scene. Ranald said of

Moriyama: "He was, by far, the most intelligent person I met in Japan."

Ranald, in fact, felt highly of all his students, for they were "very

quick and receptive... extraordinary... some of them phenomenal," all

because "their heart was in the work." On a memorial plaque on Rishiri

Island are these words (translated into English): "Those of his

students who mastered English conversation were subsequently able to

contribute to the diplomatic negotiations that took place between Japan

and the world powers of the day, and thus to save Japan from the threat

of destruction." Ranald was in Nagasaki

for only six months, during which time he was

utilized as an English instructor. A total of 14 students learned from

him, one of whom was Einosuke Moriyama, who became the chief

interpreter during negotiations with the Perry expedition in 1854, as

well as for the first American consul to Japan, Townsend Harris.

Moriyama's expertise was further utilized during Japan's first official

mission to Europe. Others among Ranald's students also helped influence

the future of Japan on the international scene. Ranald said of

Moriyama: "He was, by far, the most intelligent person I met in Japan."

Ranald, in fact, felt highly of all his students, for they were "very

quick and receptive... extraordinary... some of them phenomenal," all

because "their heart was in the work." On a memorial plaque on Rishiri

Island are these words (translated into English): "Those of his

students who mastered English conversation were subsequently able to

contribute to the diplomatic negotiations that took place between Japan

and the world powers of the day, and thus to save Japan from the threat

of destruction."Moriyama soon became Ranald's favorite pupil, no doubt because he showed the most zeal in learning the English language. Granted, Moriyama had been used as interpreter earlier during the visit in 1845 by the Manhattan, in 1846 with the survivors of the Lawrence, and in 1848 with the Lagoda crew. However, his hard work learning the English language paid off as he was able to take part in talks with American, British and Russian military representatives, and, most importantly, was able to go with the first Japanese mission to Europe in 1862. He became probably the most sought-out interpreter of English in all of Japan. The influence Ranald had on the Japanese in Nagasaki was not limited to English instruction, for in all the interrogations he underwent, he was able to relate much information regarding the Western world, e.g. geography, whaling and his own country. The reason for Ranald's extensive knowledge was that he loved reading books, and he had even brought a number of them with him in his travel chest. To him the most important book he had brought was the Holy Bible. When he arrived in Matsumae, the Japanese noticed the reverence he had toward the Bible, which Ranald explained to them as being "the book of my worship." So they made a kind of alcove shelf where Ranald could keep his sacred book, not unlike how the Japanese keep various important items on tokonoma shelves (tokowaki) in their homes. The same thing happened once again in Nagasaki after he had arrived there, where his keepers had noticed how important the Book was to him and therefore made a shelf as "a place of honor" for his Bible -- Ranald later remarked that the Japanese said he "had made a God of it."  On April 17, 1849, the USS Preble arrived in Nagasaki with its mission to pick up stranded American sailors, thanks to having received word from crewman of the Lagoda via Joseph Levyssohn, the Dutch trade superintendent (factor) in charge on Dejima. Not only were these Lagoda seamen rescued, but Ranald was sought out by the captain and included. Ranald left Japan on the Preble on April 27, 1849, and arrived in Hong Kong on May 22. The story of the USS Preble and Ranald would soon be heard around the world, with great interest shown by the US Government, resulting in Commodore Matthew Perry in Nov. 1852 setting out on his expedition to the land of Japan and arriving there in July 1853. Perry then left and returned once again in March 1854... and Japan would be changed forever. Ranald himself related that he was possibly “the instigator of Commodore Perry’s expedition to Japan.” What is certain is that those students to whom he had taught not only the English language but various customs and cultural helps to  expressing

themselves in that language, went on to help spread their knowledge and

skills in cities across Japan -- one of the stimuli to the

modernization of Japan. expressing

themselves in that language, went on to help spread their knowledge and

skills in cities across Japan -- one of the stimuli to the

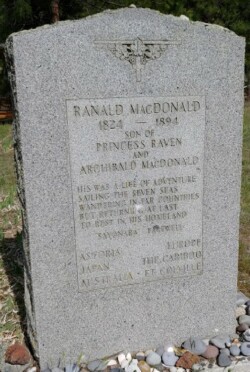

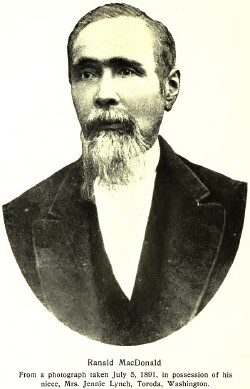

modernization of Japan.Ranald MacDonald died on August 5, 1894, at the age of 70, in northeastern Washington State where he was visiting his niece. He had been working on having his story published, a story which was not entirely unknown at the time, but which was overshadowed by a multitude of other stories by those who had been able to visit the new Japan. His roots were British, Canadian, Chinook and American, but what made his life of special importance was his connection to Japan and how he felt about the Japanese. Among Ranald's last writings were these remarks: "It is long, nearly half a century—since my adventure here sketched: Yet even now, after the vicissitudes, varied and wearing, of my life, I have never ceased to feel most kindly and ever grateful to my fellow men of Japan for their really generous treatment of me. In that long journey and voyage from the extreme North to the extreme South—fully a thousand miles—of their country; throughout my whole sojourn of ten months in the strange land, never did I receive a harsh word, or even an unfriendly look. Among all classes, a gentle kindness to the fancied cast-away—the stranger most strange—pervaded their general regard and treatment of me. From the time I landed on the beach of Tomassey in the Straits of La Perouse, when Inoes took me gently by the wrist, one on each side, to assist me to the dwelling of their employer, while others put sandals to my feet, to the time of my joining the United  States

Sloop of War 'Preble,' it was ever the same uniform kindness. Truly I

liked them in that congenial sympathy which, left to itself—unmarred by

antagonism of race, creed, or worldly selfishness—makes us all, of

Adam’s race 'wondrous kin.' States

Sloop of War 'Preble,' it was ever the same uniform kindness. Truly I

liked them in that congenial sympathy which, left to itself—unmarred by

antagonism of race, creed, or worldly selfishness—makes us all, of

Adam’s race 'wondrous kin.'"...after having, in my wanderings, girded—I may say—the Globe itself, and come across peoples many, civilized and uncivilized, there are none to whom I feel more kindly—more grateful—than my old hosts of Japan; none whom I esteem more highly. "...they are truly a wonder among the nations; commanding, in their present position, the respect and admiration of the world." It is no wonder, then, that on a memorial plaque (above banner photo) on Rishiri Island are engraved the words, "Ranald enjoys the honor of being the first formal teacher of English and indirectly a father of modernizing Japan." SOURCES: Native American in the Land of the Shogun Ranald MacDonald and the Opening of Japan by Frederik L. Schodt (2003) Ranald MacDonald -- The Narrative of his Life (1923) Memorials in Astoria (Oregon), Rishiri Island, Nagasaki, and Toroda (Washington) Text ©2023 Wes Injerd

|

|

No. 7

|

|

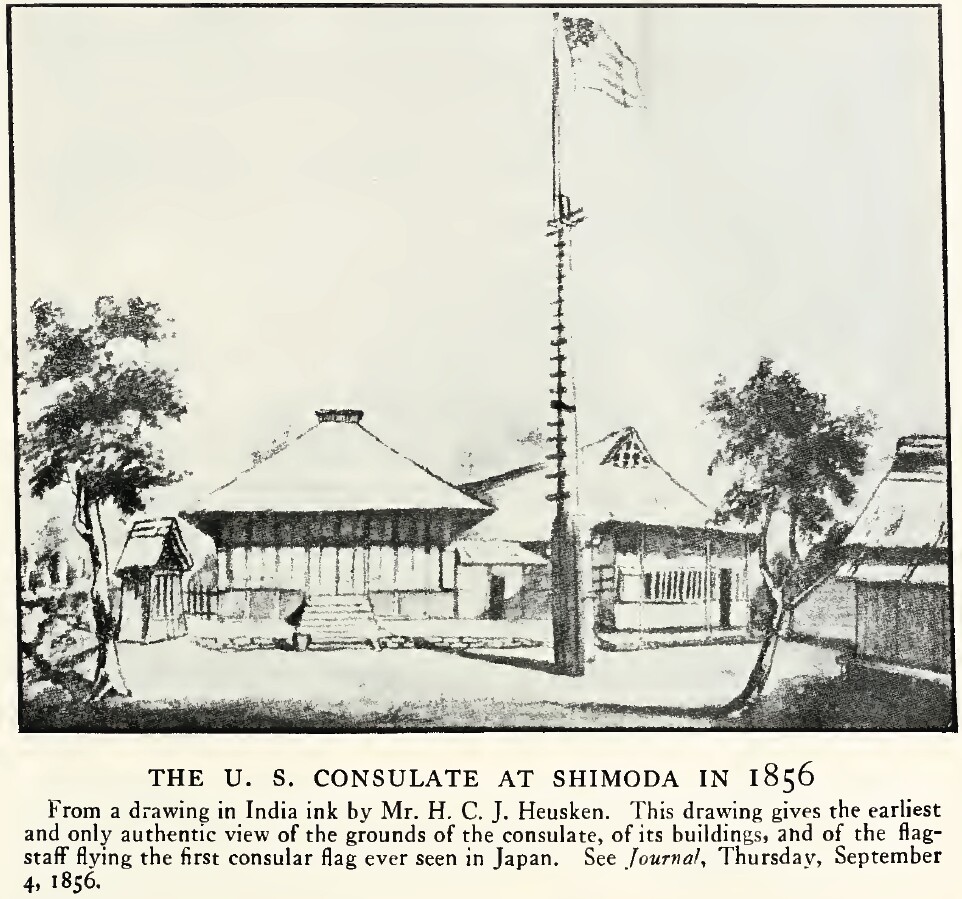

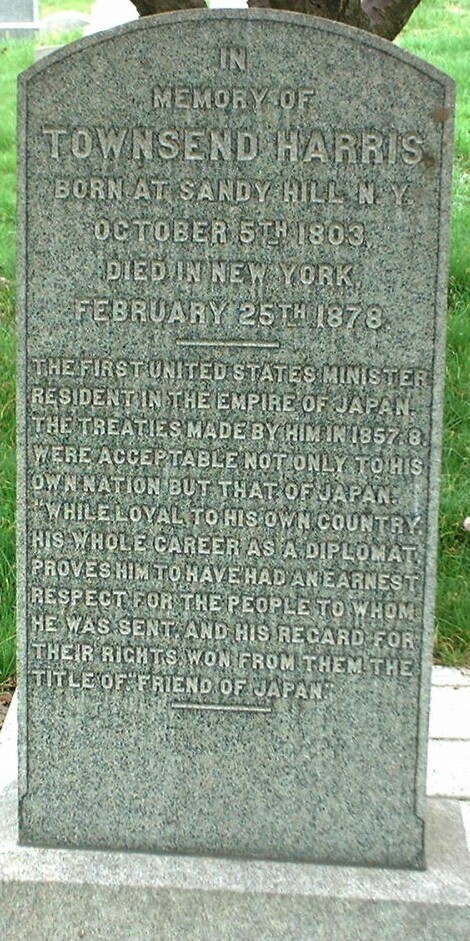

Townsend

Harris - Friend of Japan

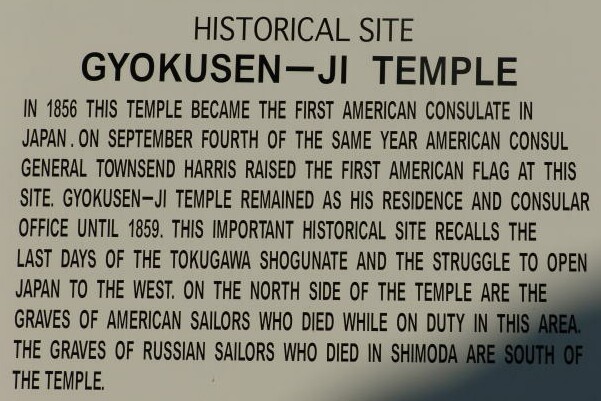

Townsend Harris, at age 51, was the first U.S. Consul-General to Japan, arriving there on Aug. 21, 1856, along with Commodore Armstrong aboard the San Jacinto. The Perry Expedition had initially re-opened the door for official foreign relations between Japan and the West in July 1853, and coming once again in March 1854. Harris was the man who helped smooth Japan's entry into a modern world and open the door for other countries to follow. Harris noted that he was arriving at an empire that was "more populous than the United States," and he continued, "I shall be the first recognized agent from a civilized power to reside in Japan. This forms an epoch in my life, and may be the beginning of a new order of things in Japan." How true were those words! Harris was a man of principle, and that principle had much of its foundation resting on the Holy Bible. Soon after he first arrived in Japan, he wrote: Sunday, August 31, 1856. A

lovely day. Write many letters. Japanese come off to see me. I refuse

to see any one on Sunday. I am resolved to set an example of a proper

observance of the Sabbath by abstaining from all business or pleasures

on that day. I do not mean I should not take a quiet walk, or any such

amusement. I do not mean to set an example of Puritanism, but I will

try to make it what I believe it was intended to be, a day of rest.

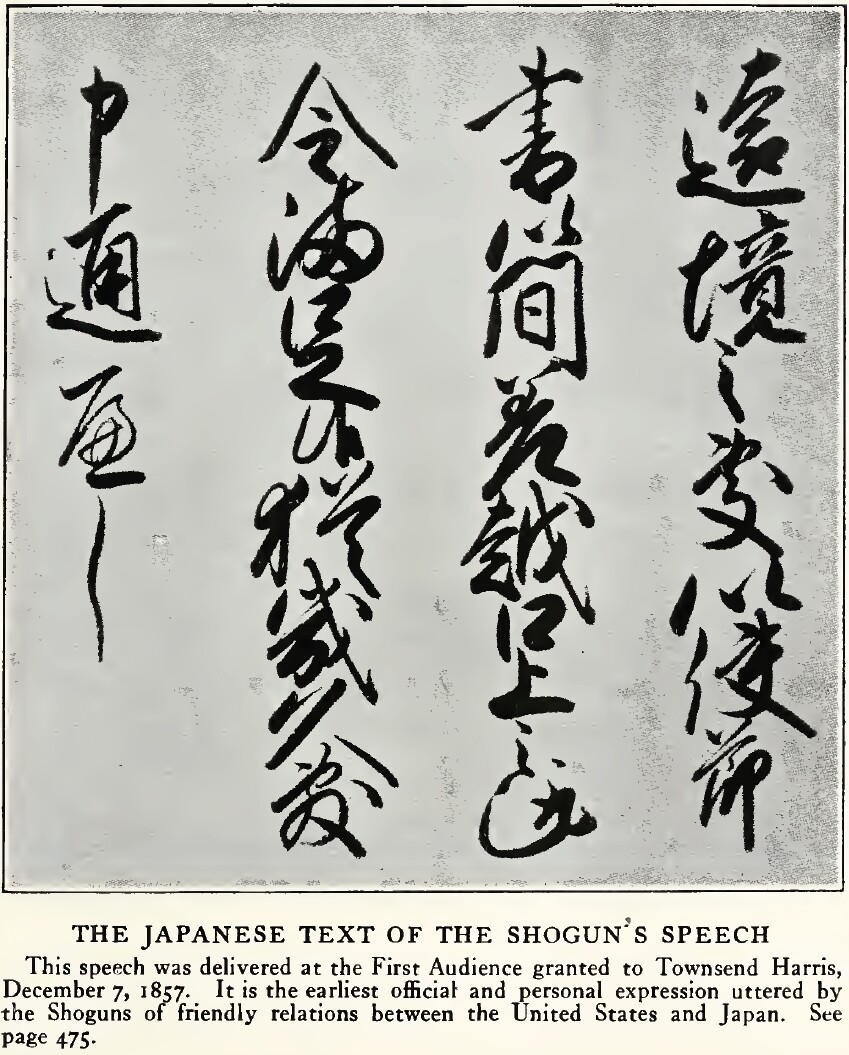

Half a year later, he noted, "I have opened the port of Nagasaki to American ships wanting supplies... missionaries may actually come and reside in Japan." And again at the end of the year, he commented along this line how much he felt that Christianity must be allowed full freedom in Japan: Sunday, December 6, 1857.

This is the second Sunday in Advent ; assisted by Mr. Heusken , I read

the full service in an audible voice, and with the paper doors of the

house here our voices could be heard in every part of the building.

This was beyond doubt the first time that the English version of the Bible was ever read, or the American Protestant Episcopal service ever repeated in this city. What a host of thoughts rush upon me as I reflect on this event. Two hundred and thirty years ago, a law was promulgated in Japan inflicting death on any one who should use any of the rites of the Christian religion in Japan. That law is still unrepealed, and yet here have I boldly and openly done the very acts that the Japanese law punishes so severely! What is my protection? The American name alone. That name, so powerful and potent now, cannot be said to have had an existence then, for in all the wide lands that now form the United States there were not at that time five thousand men of Anglo-Saxon origin. The first blow is now struck against the cruel persecution of Christianity by the Japanese, and, by the blessing of God, if I succeed in establishing negotiations at this time with the Japanese, I mean to boldly demand for the Americans the free exercise of their religion in Japan, with the right to build churches, and I will also demand the abolition of the custom of trampling on the cross or crucifix, which the Dutch have basely I witnessed for two hundred and thirty years without a word of remonstrance. This custom has been confined to Nagasaki; had it been attempted at Shimoda, I should have remonstrated in a manner that would have compelled the Japanese to listen to me. I shall be both proud and happy if I can be the humble means of once more opening Japan to the blessed rule of Christianity. My Bible and Prayer-Book are priceless mementos of this event, and when, after many or few years, Japan shall be once more opened to Christianity, the events of this day at Yedo will ever be of interest. Harris' life in Japan was not without danger. In January 1858, Harris mentioned that he had learned of a plot by certain "ronin" samurai to kill him. A large number of sentries were placed around his residence to protect him, and the "Yedo rowdies" (as he called them) were arrested. Many foreigners, it has been noted, were killed by these "cowardly swashbucklers" between 1858 and 1870, including Henry Heusken, Harris' personal secretary and interpreter, who was assassinated on Jan. 14, 1861.  The most important work that engaged Harris was, of course, his endeavors to fully open up Japan once again to the world. Harris had a very difficult time conversing with the Japanese as his English had to be translated into Dutch. What made it so hard was that the Dutch language the Japanese used when talking with Harris was what they learned from traders and sailors, and 250 years old! One interpreter was with him in the beginning, Einosuke Moriyama, who was once Ranald MacDonald's student and who had been chief interpreter for many other foreigners. Little did MacDonald know that one day his student would be so instrumental in these historical negotiations with the United States. The main points that Harris insisted upon, when speaking with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, were as follows: I told him that by

negotiating with me, who had purposely come to Yedo alone and without

the presence of even a single man-of-war, the honor of Japan would be

saved; that each point should be carefully discussed ; and that the

country should be gradually opened.

I added that the three great points would be: first, the reception of foreign ministers to reside at Yedo; second, the freedom of trade with the Japanese, without the interference of government officers; and third, the opening of additional harbors. I added that I did not ask any exclusive rights for the Americans, and that a treaty that would be satisfactory to the President would at once be accepted by all the great Western powers. One of the important points that was accepted was regarding the freedom of religion, an issue that had caused so much pain and death in the past 250 years. In this manner they went

through the treaty, rejecting everything except article 8. This article

I had inserted with scarce a hope that I should obtain it. It provides

for the free exercise of their religion by the Americans, with the

right to erect suitable places of worship, and that the Japanese would

abolish the practice of trampling on the cross. To my surprise and

delight, this article was accepted! I am aware that the Dutch have

published to the world that the Japanese had signed articles granting

freedom of worship, and also agreeing to abolish trampling on the

cross. It is true that the Dutch proposed the abolition, but the

Japanese refused to sign it.

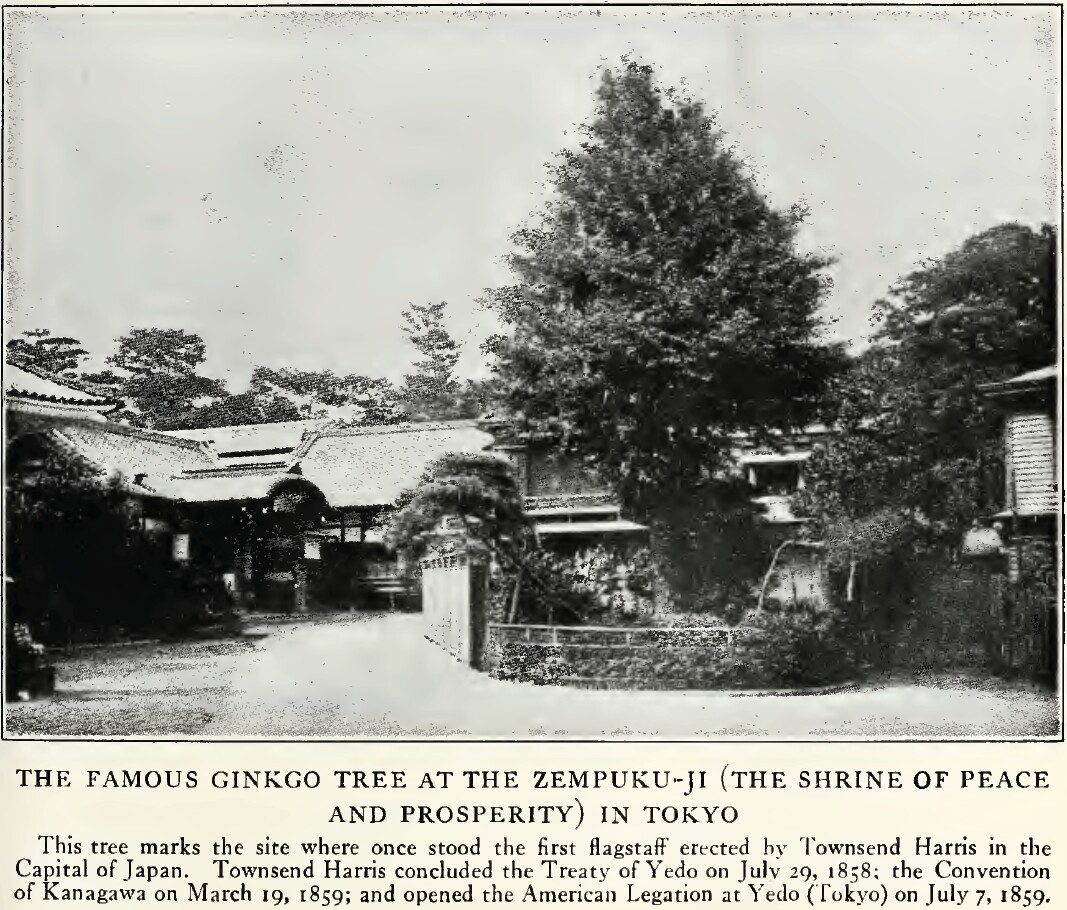

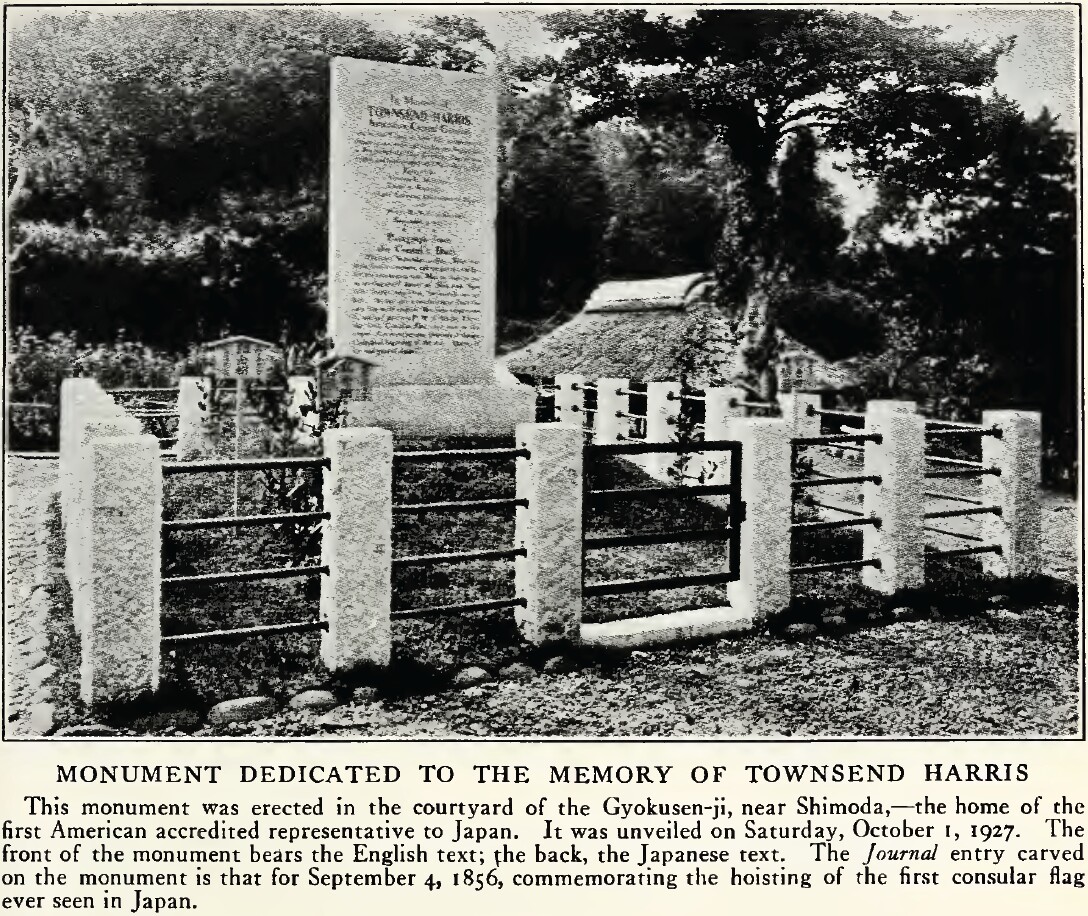

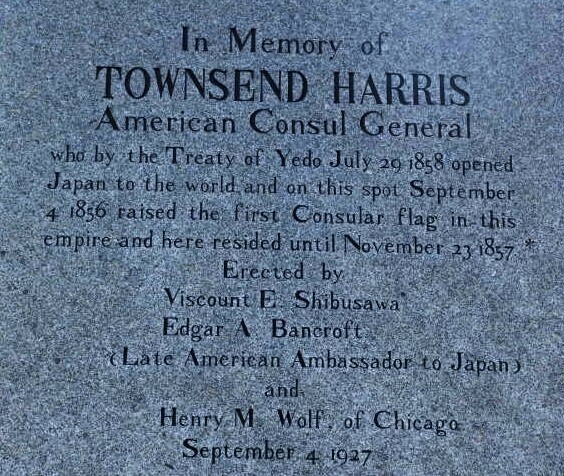

The treaty was finally signed on July 29, 1858, with a 21-gun salute. This was the basis, the first of many others countries making treaties with Japan -- British, French, Russian, Mexican, a total of 23 other nations. The US Consulate was removed from Shimoda to Kanagawa (interestingly, again at a Buddhist temple, Zenpukuji) and flag raised on July 1, 1859. A 70-member Japanese embassy traveled to the US on Feb. 13, 1860 regarding the Harris treaty. Harris also gave the considerable sum of $1,000 to help build the American Union Church in Yokohama, completed in 1875, upon the very ground of the Perry treaty. What were the benefits that Japan gained through the labors of Townsend Harris? What did he accomplish? How did he help change Japan? Here's what his early biographer had to say: Old Japan of Mr. Harris's

days has vanished, and in New Japan life is more than worth

living for the average man. Such popular freedom and advantages were

never before known. Instead of the caste, monopoly, cramping laws,

repressive customs, and cruel government of former days, the common

people live in a new world of rights, privileges, and possibilities.

New institutions, codes, and ideals have come in. The land is for the

most part owned by the men who till the soil. The courts are open to

every one, and justice is cheap and easy to obtain. Schools invite all

to enter. Once only samurai could be soldiers ; now the army and navy

are filled without regard to class by enthusiastic conscripts. The men

are well fed, well paid, well taught, and well nursed in time of

sickness. The old sectional jealousies, sectarian bigotries, and

political hatreds are vanishing. Wealth, comfort, happiness, national

unity, and population are steadily on the increase. With over two

thousand miles of railway, with telegraphs, lighthouses, post-offices,

newspapers, savings banks, hospitals, and most of the appliances of

modern civilization, life seems very rich and full to the lad and lass

born in this " era of Meiji " (1868-1895+).

Japanese travelers and enterprising adventurers are now found in many countries. Immigrants by thousands dwell in Hawaii, the United States, Australia, Mexico, Korea, China, and in British, Russian, Dutch, Spanish, and French Asia. With her population increasing at the rate of over half a million a year, it is necessary for Japan to expand and colonize. Her desire and ability to do both are manifest. These facts explain in part also why so small a nation did not hesitate, when peace seemed no longer possible, to go to war with colossal China. When in 1870 the Japanese abolished feudalism, they rejected also most of the ideas of government and society borrowed from China and from Confucius and his commentators, and adopted those of the Western World... It was not a new thing in Asiatic history when China and Japan began hostilities in the summer of 1894, but it was in a wholly novel way. Each published a formal declaration, and appealed to the sympathies of Christendom. Japan proceeded according to international law, and with scientific and Christian-like methods. A superb hospital corps, trained nurses, the Red Cross Society, and the absence of privateers were noticed. In old Japanese times the wounded in battle committed suicide, were left to die on the field, or received only blacksmith surgery. These days are over. Yes, these days are over, and a new Japan has been born, in great part to the tireless work of this one man. Though there were "two hundred years of Dutch leaven" in the land, Harris was the one who brought those years to fruition, He was the bridge to the new Japan, and missionaries along with many other foreigners helped educate Japan. The Japanese no longer followed feudalism and Confucian thought, but were liberated to grander ideas. As they built a powerful military, able to conquer almighty China in the battle over Korean sovereignty, and gained strong economic power through manufacturing, they became equals in the world system. The status of and honor toward women changed in Japan also as Christian teachings became widespread. Hospitals and nurses became more and more common, including the Red Cross treatment of the wounded rather than let them die on battlefields. Harris left Japan for New York on May 11, 1862. His nickname in the city was "the old Tycoon," which came from the Japanese name for the emperor, taikun, which later became tenno. Harris died on February 25, 1878, at the age of 73. Though in Japan for a short time, his legacy will always remain as one of the most influential foreigners who helped change Japan into the great country it is today. SOURCES: The Complete Journal of Townsend Harris: First American Consul and Minister to Japan (1930) Townsend Harris: First American Envoy in Japan by William Griffis (1895) Text ©2024 Wes Injerd

|

| "Behind

almost every one of the radical reforms that have made a new japan

stands a man -- too often a martyr -- who was directly moved by the

spirit of Jesus, or who is or was a pupil of the missionaries." "The study of the English language was not only systematically introduced and fostered by American missionaries, but it was they who awoke the hunger and continued interest of the Japanese. Verbeck knew many languages, but he advised the use of English as the basis of general use and popular education, and of German for science. This advice was taken by the men of the new government who were high in office and influence. "Who was it that provided first the phrase books and grammars, and then the colossal standard dictionary of Japanese-English and English-Japanese on which the multifarious library of helps since made have been based? We answer, the same who translated the Bible into Japanese and thus 'built a railway through the national intellect' -- the missionaries." -- from Christ the Creator of the New Japan by William Griffis (1907)

|

Channing Williams - June 1859

James Hepburn and Samuel Brown -

Oct-Nov 1859

"In his simplicity and modesty [Verbeck] is a model

and in his power a perfect wonder.

The half of his work and his influence has not been told."

-- Henry Stout, successor to Guido Verbeck in Nagasaki

|

No. 10

|

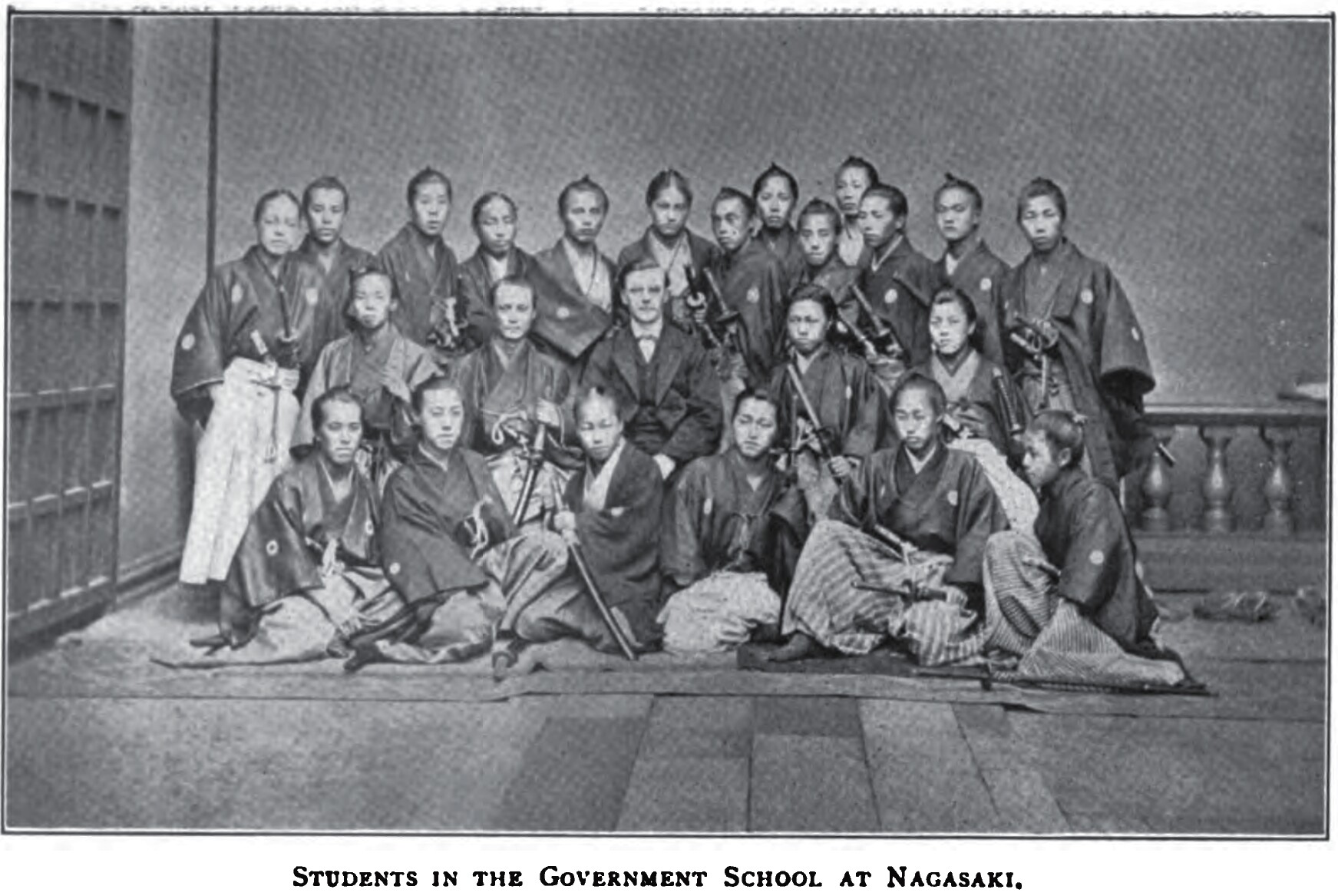

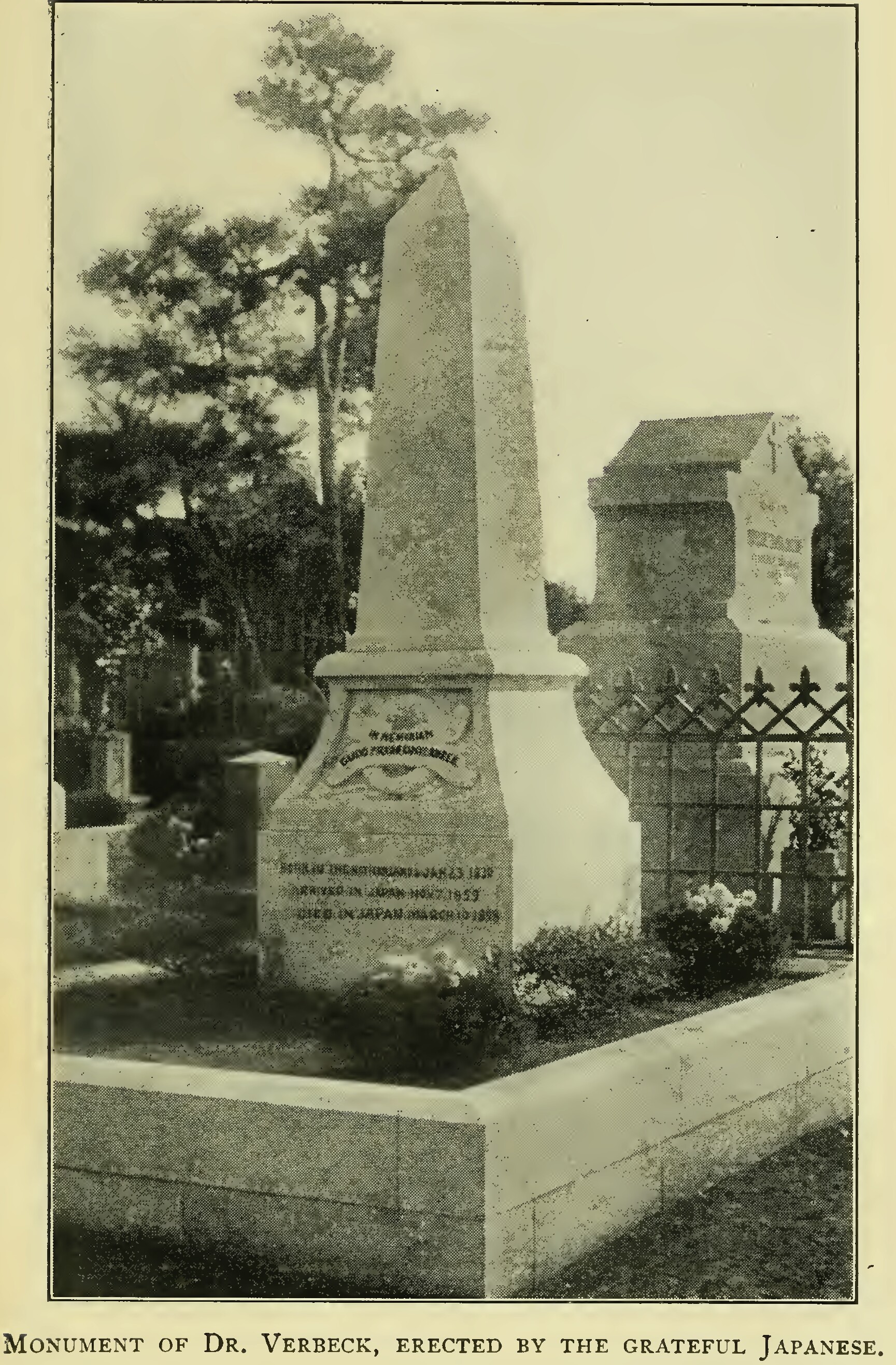

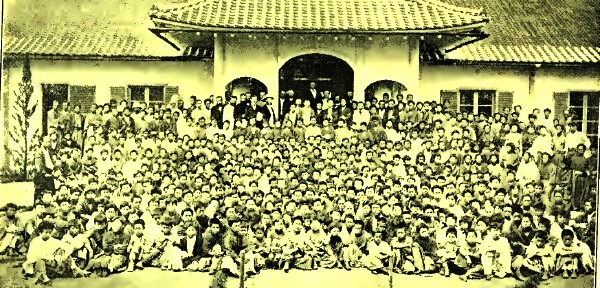

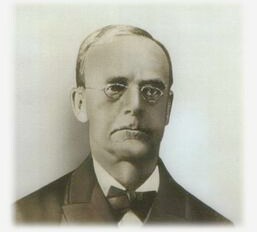

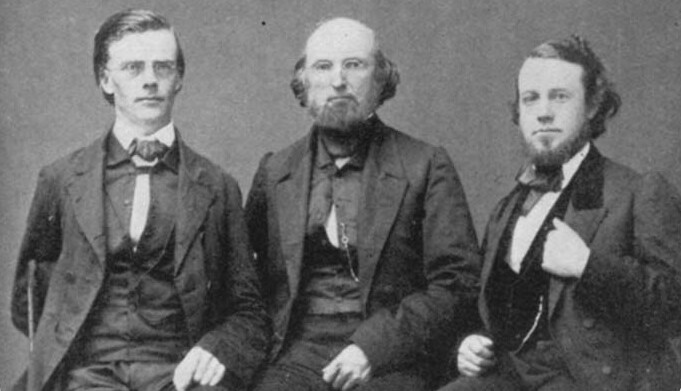

Dr. Guido Herman Fridolin

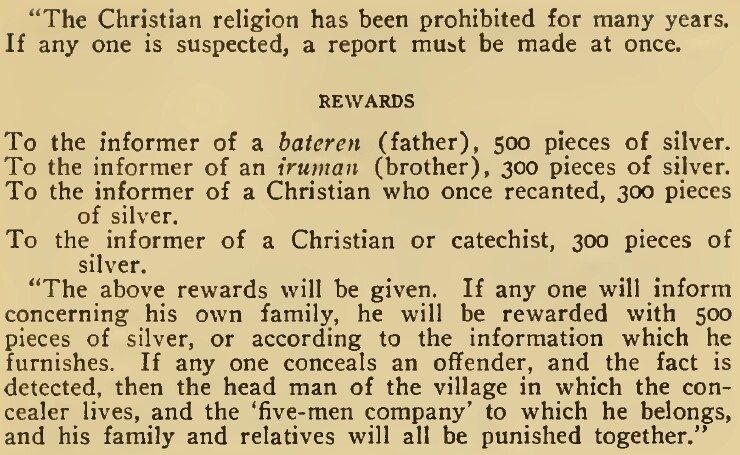

Verbeck was born in Zeist, Holland, on Jan. 23, 1830. He came to Japan

on Nov. 7, 1859, and spent nearly 40 years there in indefatigable work,

especially religious, to help build a new Japan, implanting "all the

western things, which have been the result of several hundred years'

labor." He was one of the first oyatoi

gaikokujin, foreigners employed by the Japanese Govt. to teach

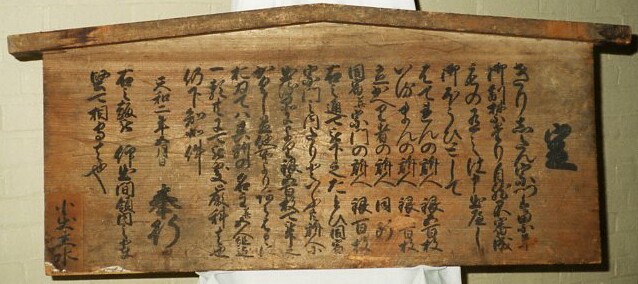

western culture to a land of some 30 million people. Verbeck's traveling companions and fellow missionaries, Rev. S. R. Brown and Dr. Duane B. Simmons Verbeck spent the first ten years in Nagasaki, the next ten in Tokyo as an educator and translator for the Japanese Government, the tne next twenty years in Bible translation and traveling around Japan. His main purpose in being in Japan all those years never changed -- to preach Christ to the people. When asked why he didn't study the religions of Japan, he said that it was not worth spending time on teaching that 2+2=5, but much more effective to show that 2+2=4! Verbeck spent much time on learning not only modern Japanese, but ancient and medieval as well, all to improve how he communicated with those in the land he loved. Verbeck first sought the help of Townsend Harris in finding the first American Episcopalian missionaries to Japan, Rev. John Liggins and Rev. M. C. Williams, which were both eagerly awaiting Verbecks arrival. Verbeck chose Nagasaki as he felt it was "the place best adapted for missionary operations at present in Japan." Williams would later start the first Protestant church in Japan in Higashi-yamate, Nagasaki, in Sept. 1862, with Verbeck the song leader and playing the harmonium, a pump organ that worked well even in subtropical climates such as in Kyushu. After registering with the US Consul (for protection), he found a house in Nagasaki (rent was $16/month) and when his wife, Maria, arrived later on Dec. 29, 1859, they soon welcomed a little baby girl on Jan. 26, 1860, whom they named Emma Japonica and who Guido called, "the first Christian infant born in Japan since its reopening to the world." Sadly, though, the baby was not meant to be long in their arms, for she died the next month on the 9th and was buried in the Inasa Cemetery. Mr. and Mrs. Verbeck, however, would later go on to parent five sons and two daughters, one of whom would carry on the name Emma Japonica.  Sign against Christianity in Nagasaki when Verbeck arrived (1859) The first years in Nagasaki for the Verbecks were spent in language and culture studies, and most importantly, teaching English (also Dutch and German?) to Japanese interpreters, a number of whom would be important leaders in Japan's future. So successful were the students under Verbeck's tutelage that the Shogun's magistrate in Nagasaki established a language and science school, the Yogakusho, in Edo-machi (later moved to Omura-machi and called Gogakusho, then moved to Shin-machi and called Saibikan, then called Kounkan in 1868). The number of students would grow to over one hundred, and included a great number of important people in the new Meiji government - Toshimichi Okubo, Kogoro Katsura (Takayoshi Kido), Tomomi Iwakura, Shigenobu Okuma, Ministers Taneomi Soejima and Hirobumi Ito. So popular was this new school, that other leaders (daimyo) wanted the same for their areas -- Kaga, Satsuma, Tosa and Hizen. The Chienkan English school in Nagasaki (in present-day Goto-cho), founded by the Saga clan lord Nabeshima in 1867, became quite famous when Verbeck taught English there for two years until 1869, using for his textbooks the Bible (New Testament) and US Constitution. It was run by Shigenobu Okuma, who taught in the school as well, with over 100 students being enrolled at one time. Okuma would later go on to found Waseda University in Tokyo. Count Okuma, by the way, compiled two extensive volumes on the Meiji Era, entitled, Fifty Years of New Japan (1910). Okuma, of the Saga Clan, studied English under Verbeck in Nagasaki, later established Waseda University in Tokyo in 1882 and was Prime Minister of Japan twice, in 1898 and then from 1914 to 1916. There are a number of other names which are quite well-known to most Japanese today. In a famous photo of Verbeck's students, one can find such names as Ryoma Sakamoto, Kaishu Katsu, Takamori Saigo, and even Emperor Meiji is noted. Truly Verbeck touched many a young Japanese who would later become leaders. it is noteworthy that the books Verbeck gave many of these young men were the New Testament, US Constitution and Declaration of Independence.

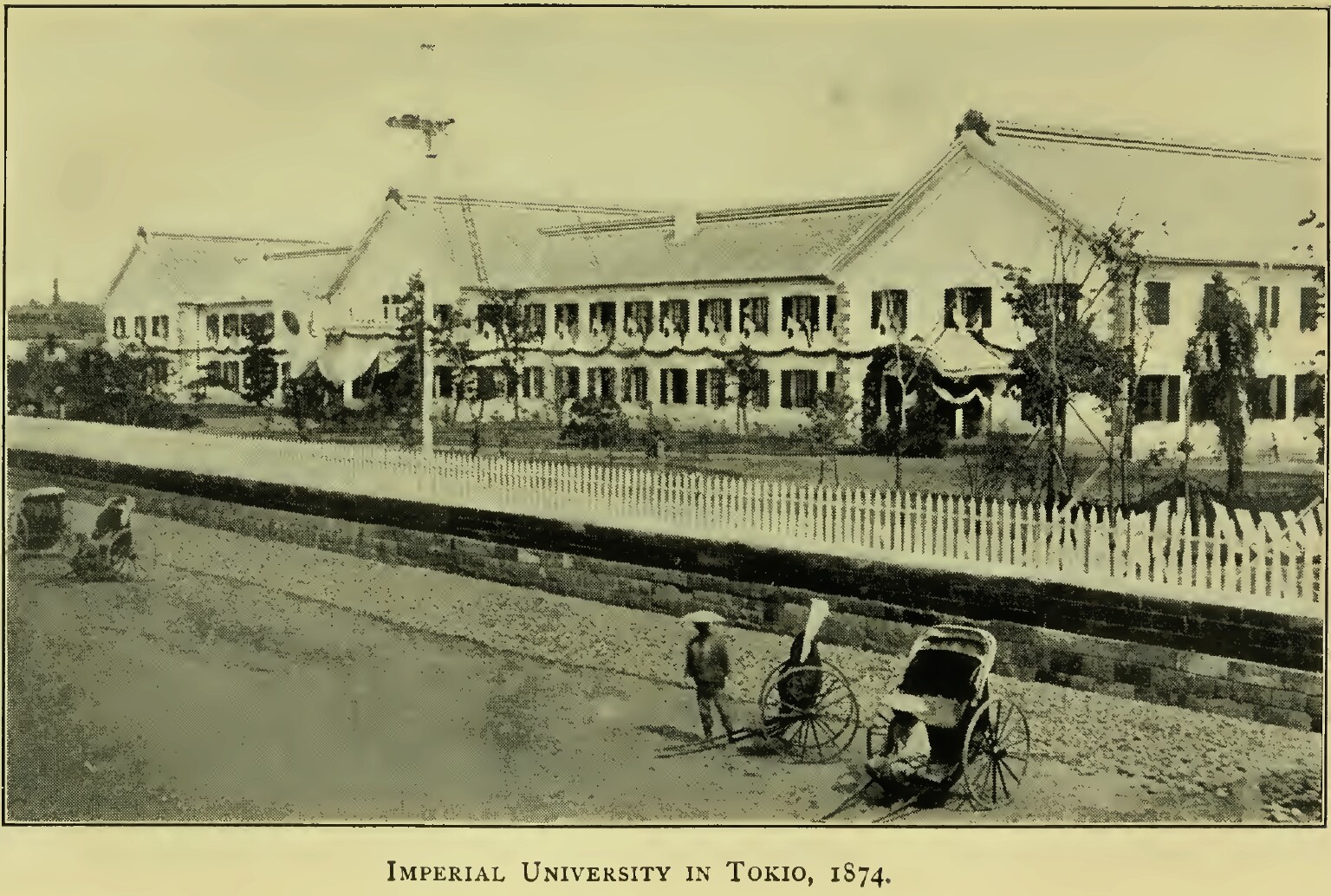

The "first Christian service held on Deshima, since more than two centuries," was in a large room above a warehouse, after moving from a local Buddhist temple, Sofukuji (Ranald MacDonald had stayed there). In June of 1862, Verbeck had his first Bible class with only two Japanese (Murata Wakasa no Kami and his brother, Ayabe), one of whom the next month commented that "the exclusiveness of his country and any past misunderstandings with foreigners, were owing to a want of knowledge of the nature and tendency of the Christian religion, and that the best preventive of future troubles would be to acquaint his countrymen with these, and that therefore he would write out my explanations in the common popular style of writing." By the end of 1862, Verbeck would have a total of four students learning the Bible and English two or three times a week. The year 1863 proved to be quite dangerous for foreigners in Japan, a number of whom were murdered by ronin samurai. Verbeck was warned and therefore he moved to Dejima where his influence was even greater, God working in mighty ways even in the midst of social upheaval. One of the great ways God worked was through the British envoy, Sir Henry Parkes, who had sided with the Emperor rather than the Shogun, on whom most other foreign ministers had placed their support. Verbeck had also been on the same side as Parkes, which was for the best, though unknown at the time to either of the men. Two young Japanese to whom Verbeck had taught English in 1860 had so impressed the Governor of Nagasaki that he proposed to the Shogun that a foreign language and sciences school be founded with Verbeck as the principal. It was not long after that a school was founded where Verbeck taught two hours a day five days a week. There were soon over 100 students, with Verbeck teaching the advanced classes. Samurai and nobility from all over Japan came to Nagasaki to learn under Verbeck. The chief "textbooks" which Verbeck used were New Testament and the US Constitution. Other classes included subjects such as astronomy, mathematics, navigation, surveying, chemistry and physics. Murata Wakasa no Kami (Kubota Wakasa) found a book floating in the waters off the coast of Nagasaki and had it translated into Chinese. It was a book that was an "account of the character and work of Jesus Christ," which account so affected Murata that he became a student in Verbeck's Bible class and later became a Christian. Along with his brother, Ayabe, the two were Verbeck's first converts in Japan, being baptized on May 20, 1866. Another young man, Motono, was also baptized with them. In 1866, Verbeck was also instrumental in introducing two young Japanese, Ise and Numagawa Heishiro, to study shipbuilding and navigation at a school in New Jersey in the United States, and who later went on to study at the US Naval Academy. Verbeck helped two other students from Higo to attend Rutgers College in New Jersey. Verbeck would eventually introduce more than 500 Japanese youth to schools in America. Verbeck's first trip to mainland Japan was on Oct. 18, 1868, and he visited Kobe and Osaka, then returned to Nagasaki. February 1869 proved to be a most important month for Verbeck, when he was asked by some of his former students in the Government to establish a school in Tokyo, the Daigaku Nanko -- a school which would later be known as the prestigious Imperial University (now known simply as Tokyo University). He quickly accepted the task, but before leaving Nagasaki, prepared for another move, involving his wife and children to California. In June 1870 started a new life and work in Tokyo, helping to establish the Tokyo college. After becoming president of the college, Verbeck was involved in perhaps the greatest of his endeavors to help the people of Japan -- his initiating and planning with other Japanese to send a diplomatic mission to the United States, a mission known to every student of Japanese history as the Iwakura Mission. Dr. Verbeck's share in planning this embassy was little known at the time, and his policy was always to conceal his influence. Of this mission, Griffis wrote, "Perhaps the two greatest services which Verbeck rendered were the translation of the Western law books, law codes and books on political economy and in ternational law, and the projection of the famous Iwakura embassy. This was a body of the most influential men of the empire sent abroad to America and Europe. In America Joseph Hardy Neesima, then a student here, was attached to the embassy as an interpreter... This embassy accomplished all that Dr. Verbeck had hoped. The nation moved forward more rapidly and steadily than ever, and, best of all, the noticeboards against Christianity were taken down and the door for missionary work began to open widely."

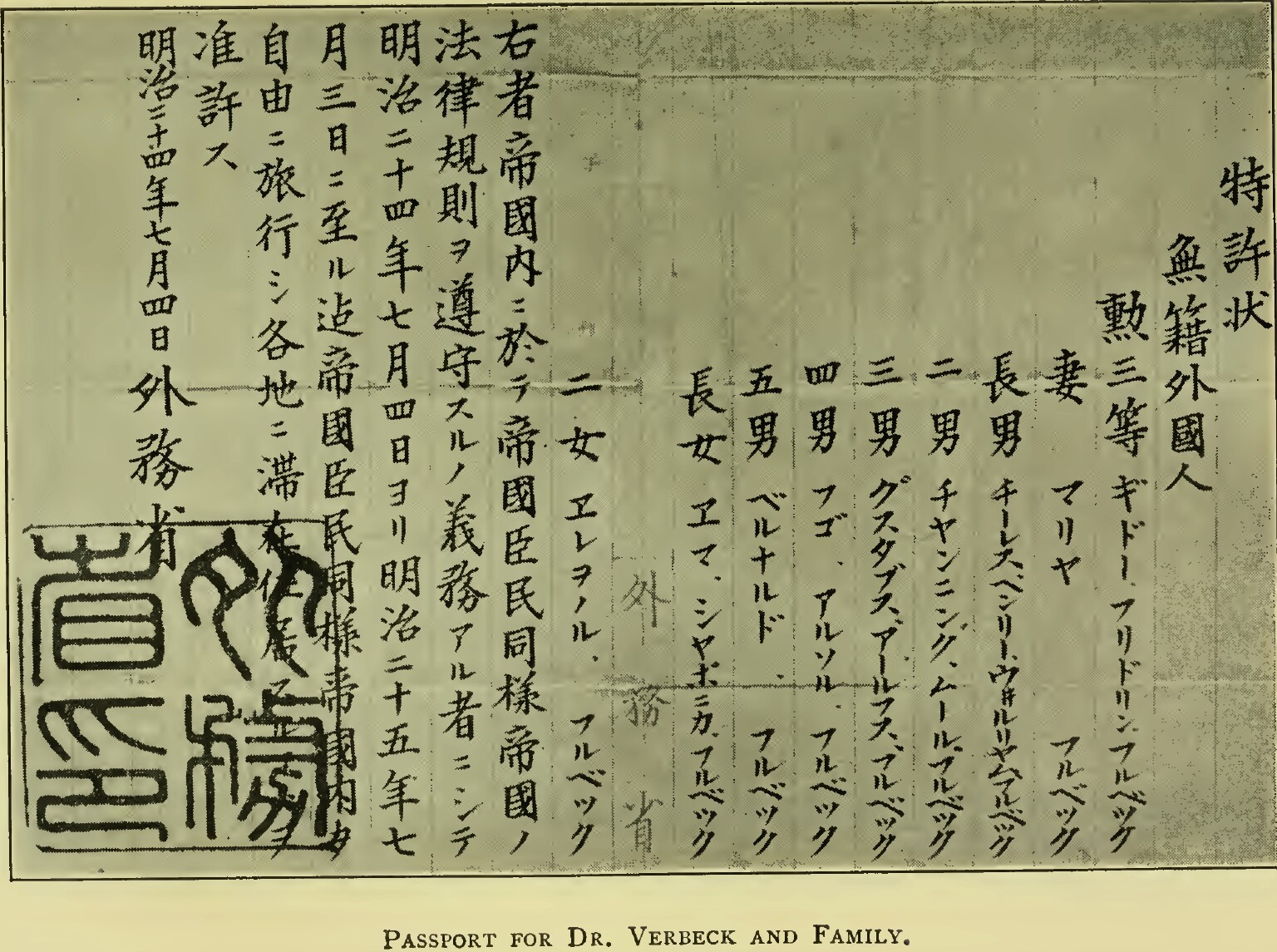

Verbeck served five years as adviser to the Senate which was preparing a national constitution and parliament -- Verbeck's part in the formation of New Japan cannot be underestimated, for he no doubt had a great influence on Iwakura. This work he continued until 1877 when he decided to devote all his time to his main love -- missionary work. To show Japan's appreciation for all he had done, the 18-yr-old Emperor of Japan bestowed upon him the decoration of the third class of the Order of the Rising Sun. Later Verbeck would also teach at Meiji Gakuin for about ten years. However, he was not only a teacher of the elite. He felt that in order to reach the Japanese for Christ, missionaries must not forget the common person -- "It is the people we must reach, the people." Verbeck, having an excellent command of the Japanese language, was able to speak with in numerous theaters and halls and churches. He also taught in theological schools and helped with translating the Bible into Japanese. In a letter of Feb. 21, 1870, Verbeck wrote that he had the entire New Testament and some books of the Old Testament translated into Japanese from a Chinese translation, via a Chinese scholar, though non-Christian. So intense was Verbeck's desire for a Japanese translation of the Bible that he personally asked that a young man be sent out as a missionary with the task of translation. Verbeck even offered free room and board and would pay a 1/4th of the young man's yearly expenses. One of his last projects was a translation of the Bible into Japanese, working along with Hepburn and others. Verbeck was to address the Emperor and present him with a copy of the Bible. James Ballagh, who worked with Verbeck and spent over fifty years in the land, wrote: "Is not this a fitting sequel to a life so singular in humility and devotion to be able not only to disarm prejudice from the minds of the Government of Japan, but to present to His Majesty a copy of that Blessed Word of God upon which all his own hopes were founded for eternity?" Verbeck was able to accomplish so many things in Japan, yet he had no country he could call his own -- he had lost his Dutch nationality when he moved to the US as a child, he had never obtained US citizenship, and Japan had no naturalization laws yet. He did feel that Japan was his land, and in 1891 he applied for Japanese protection, writing a letter humbly explaining his situation and desire. Griffis wrote: "The Japanese Government granted him his request and took him and his family under its protection and gave him and them the right, which no other foreigner then enjoyed, "to travel freely throughout the empire in the same manner as the subjects of the same, and to sojourn and reside in any locality." The Minister of Foreign Affairs, in sending him this statement, wrote: "You have resided in our empire for several tens of years, the ways in which you have exerted yourself for the benefit of our empire are by no means few, and you have been always beloved and respected by our officials and people."  Passport issued to Verbeck family by Japanese Govt., July 4, 1891 Names of wife, five sons, and two daughters listed. Verbeck died in Tokyo on March 10, 1898, at the age of 68, and was buried in Aoyama Cemetery, the only pioneer missionary to be buried in Japan. Tokyo City donated to his family a burial plot and the Emperor himself helped pay for funeral expenses. Not unlike his predecessor of the 17th century, William Adams, Verbeck served the government of Japan, teaching and advising young and old Japanese for some twenty years. Truly Japan of the 21st century is indebted to this one man for helping to bring Japan to such societal, political, and religious change.

"Of

the many foreigners who have helped Japan according to their ability,

the greatest, wisest, and therewith the gentlest and most unassuming of

all, was Dr. Guido F. Verbeck."

-- Hartshorne in Japan and Her People (1904) Sources: Verbeck of Japan: A Citizen of No Country by William Griffis (1900) Verbeck of Japan: Guido F. Verbeck as Pioneer Missionary, Oyatoi Gaikokujin, and “Foreign Hero” by Ion Hommes (2014)

Text ©2024 Wes Injerd

|

Jonathan Goble - 1853, 1860

L. L. Janes - Aug. 1871

William S. Clark - June 28, 1876

Christ the Hope of Japanby

This Spirit of Jesus is the soul of the liberalizing forces of Japan.

The transforming power of Christianity has already had much to do in

bringing about the social changes that are so readily noted by those

who have followed the history of Japan during the past fifty years. To

tell of even a few of the changes in the civilization of Japan since

1870 is to picture again the England of the 12th Century. Then there

was not a chimney in the land; no windows; no chairs, no public

hospital, no lighted streets at night; there were beggars by the

thousands, gamblers and social outcasts by myriads. |

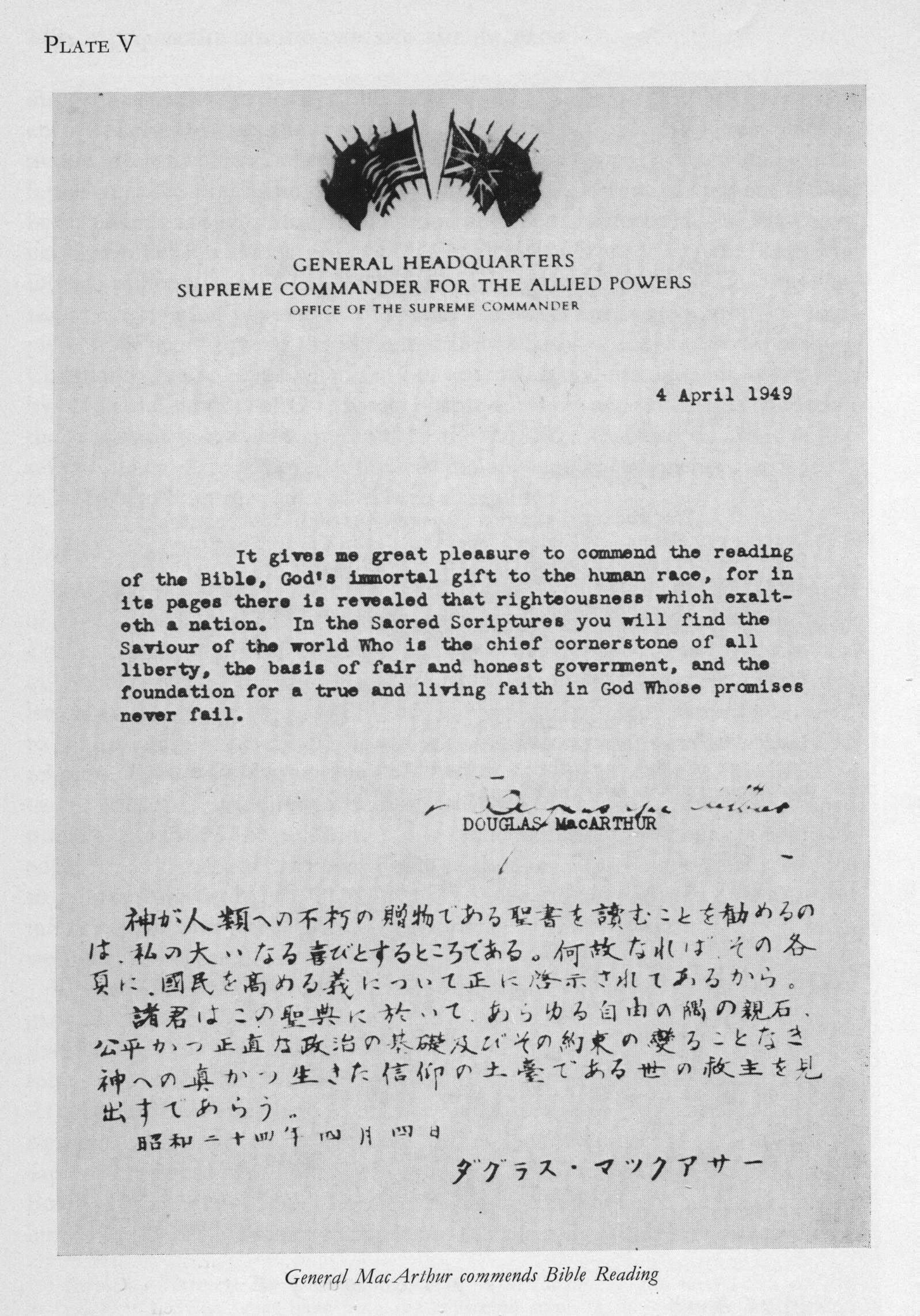

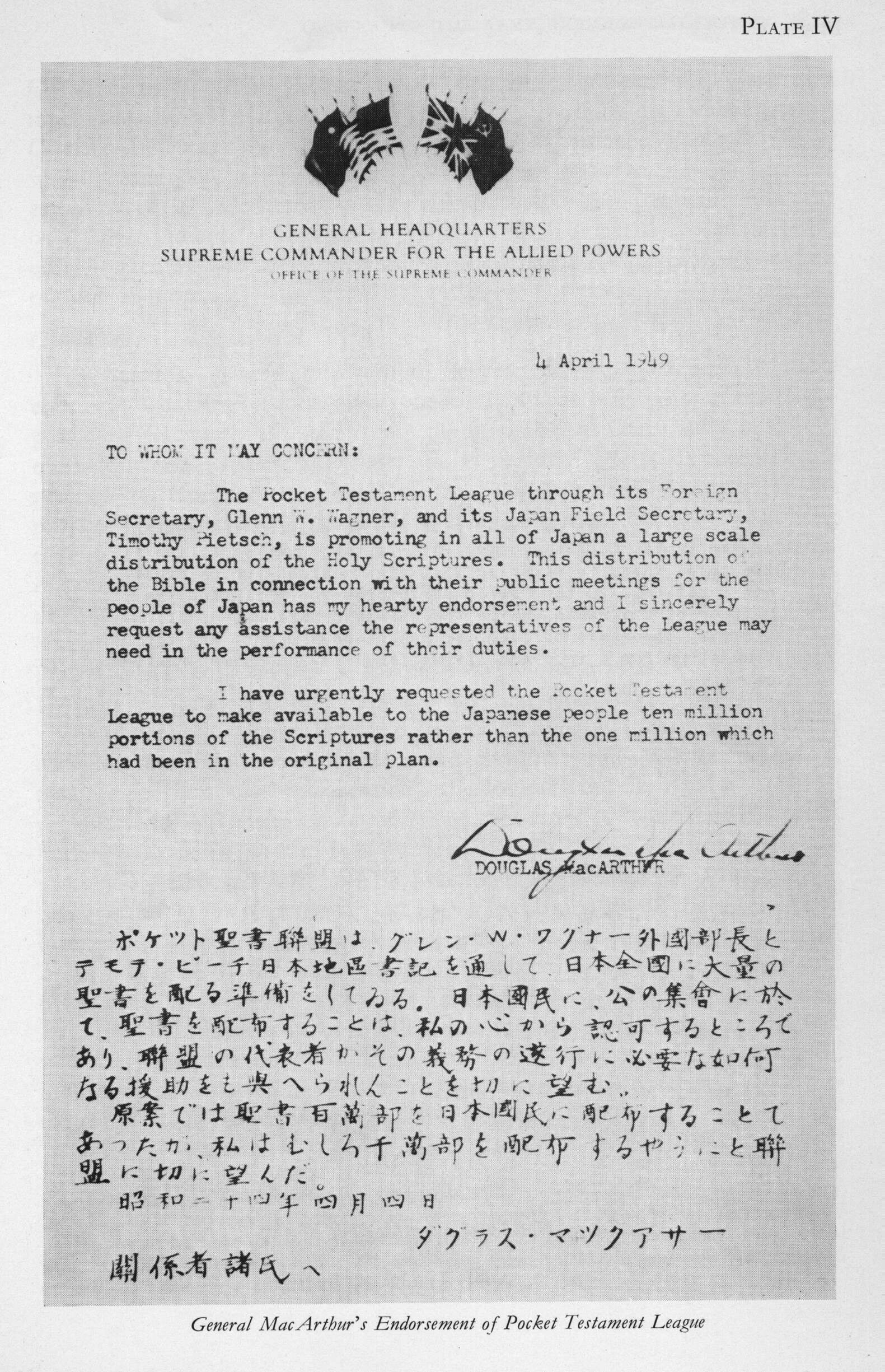

MacArthur commends Bible reading to the Japanese and

requests 10,000,000 New Testaments to be distributed

April 4, 1949

Source: The Allied Occupation of Japan 1945-1952 and Japanese Religions

by William P. Woodard (1972)