Materials for Circle Activities

01

The King's Speech

The red light on the microphone starts to blink.

Logue joins the others.

The Reader is at a smaller microphone near the ad hoc `broadcast booth.

Five, four, three, two...

BBC NEWS READER : Good evening, this is the BBC National and World programme,

broadcasting from Buckingham Palace.

During this, Bertie(King)'s hands begin to shake,

the pages of his speech rattle like dry leaves,

his throat muscles constrict, the Adam's apple bulges,his lips tighten...

all the old symptoms reappear.

Elizabeth grasps the sides of her chair with white knuckles.

Lang's eyes roll heavenward.

Churchill studies the situation, ready to leap into the breach.

Bertie(King) and Logue stare at each other.

Logue smiles, perfectly calm, totally confident in the man he's worked

with.

His confidence is contagious.

Bertie takes a deep breath and lets it out slowly.

His hands grow steady, his throat muscles relax...

all the things he's practiced.

The luminous dial of a wireless. Unbearable silence. Then:

BERTIE (King):

In this grave hour, perhaps the most fateful in our history,

I send to every household of my peoples, both at home and overseas...

...this message spoken with the same depth of feeling for each one of you

as if I were able to cross your threshold and speak to you myself.

For the second time in the lives of most of us we are at war.

For we are called, with our allies, to meet the challenge of a principle

which,

if it were to prevail, would be fatal to any civilized order in the world.

It is the principle which permits a State, in the selfish pursuit of power,

to disregard its treaties and its solemn pledges;

which sanctions the use of force, or threat of force, against the sovereignty

and independence of other States.

Such a principle, stripped of all disguise, is surely the mere primitive

doctrine

that might is right, and if this principle were established throughout

the world,

the freedom of our own country and of the whole British Commonwealth of

Nations would be in danger.

But far more than this -

the peoples of the world would be kept in the bondage of fear,

and all hopes of settled peace and of the security of justice and liberty

among nations would be ended.

This is the ultimate issue which confronts us.

For the sake of all that we ourselves hold dear,

and of the world's order and peace,

it is unthinkable that we should refuse to meet the challenge.

It is to this high purpose that I now call my people at home

and my peoples across the seas,

who will make our cause their own. I ask them to stand calm, firm,

and united in this time of trial.

The task will be hard. There may be dark days ahead,

and war can no longer be confined to the battlefield.

But we can only do the right as we see the right,

and reverently commit our cause to God.

If one and all we keep resolutely faithful to it,

ready for whatever service or sacrifice it may demand, then,

with God's help, we shall prevail.

We may all find a message of encouragement in the lines which,

in my closing words, I would like to say to you:

`I said to the man who stood at the Gate of the Year,

"Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown."

And he replied, "Go out into the darkness,

and put your hand into the Hand of God.

That shall be to you better than light,

and safer than a known way.'

" May the Almighty Hand guide and uphold us all.."

IN THE AD HOC `CONTROL BOOTH' AREA -

the Manager makes a `cut'gesture to Bertie, he's off the air,

the red light on the microphone goes out.

The Manager points, and the red light on the Reader's microphone goes on.

BBC NEWS READER:This concludes the BBC broadcast of the King's Speech.

WINSTON CHURCHILL: Couldn't have said it better myself.

The ultimate compliment.

COSMO LANG: I'm speechless.

ELIZABETH: Thank God.Well done, Bertie. Well done......Lionel. Well done.

LIONEL: I always called you Bertie. Today, I call you King.

He offers his hand. But instead of taking it,

Bertie takes him by the shoulders and gives him a hug.

This is a long way from the five pace rule. The last barrier has fallen.

THE END

関連You tube: The King's Speech - World War Speech

02

My Fair Lady

A Sad Day for Higgins

Back at Higgins' flat, at about eleven o'clock that same morning,

Higgins was shouting from his room.

'Pickering! Pickering! Eliza's gone!'

Pickering came in. `Gone?'

`Yes. Gone! Run away! What am I going to do?

I can't find where anything is and I don't know who's coming

to see me this morning. Eliza knew all that, but she's gone.'

`Higgins, did you bully her again last night?

Is that why she's run away?' Pickering asked.

`Just the opposite - she bullied me. She threw my slippers at me.

I don't understand it - we were so good to her.

Please, Pickering, do something! Call the police! I want to find her!

She belongs to me! I paid five pounds for her!'

`The police? Good idea.' Pickering picked up the phone.

Higgins went on, 'Why did she go? I can't understand it at all!

Women are never sensible! They've got heads full of wool, stupid

things!

Why can't women be more like men, that's what I want to know?

Why can't women be like us?'

At about the same time, Eliza was at Mrs Higgins' house.

`You mean that you did this wonderful thing for them at the Ball,

without one mistake, and they never said how wonderful you were?

Never said thank you?' Mrs Higgins asked.

`Not a word,' Eliza answered.

`That's terrible, my dear. Really terrible!'

Eliza started to smile, but her smile quickly disappeared

when she heard Higgins' voice from the front door.

'Mother! Mother!'

'Stay where you are, my dear,' Mrs Higgins said to Eliza.

'Mother! The most terrible thing has happened ...'

Higgins said, hurrying into the room.

He stopped when he saw Eliza.

'You!' he shouted.

'How are you, Professor Higgins. Quite well, I hope?' Eliza said.

'Will you have a cup of tea?'

'Don't you try that game on me!' Higgins shouted back.

'I taught you! Now get up and come home and stop being so stupid!

You've given me enough trouble for one morning!'

'Very polite, Henry! What a nice way to ask a young lady

to come to your house!' Mrs Higgins said to her son.

'Now you be polite to Eliza or I'll ask you to leave.

Why don't you talk to her about the weather or something?'

Then Mrs Higgins turned and left them together.

Higgins sat down and took a cup of tea.

'Well, Eliza, you've paid me back now. Have you finished?

Or do you want more? I'll be quite all right without you, you know ...'

But then his voice changed, 'But I will miss you, Eliza.

You've taught me a few things, too'

'You've got my voice on your recording machine.

You can turn that on any time you want to hear me,

and you can't hurt machines, can you?

What do you want me back for?'

'Oh, I see,' Higgins answered.

'You want me to be in love with you or something, do you?

Like Freddy? Is that it?'

Eliza did not know what to say for a minute. Then she said,

'No, that's not it. I just want you to be kinder to me.

I stayed with you, not for the new dresses and the taxis,

but because we were pleasant together.

I felt friendly towards you'

`Yes, of course. Well, Pickering and I feel the same.

You're being stupid.'

'Oh! I can't talk to you: you turn everything against me.

I'll marry Freddy, that's what I'll do. He loves me'

`Freddy! Freddy is a good for nothing!

Woman, you don't understand! I have taught you to be a real lady

- you can't go and marry a man like Freddy!'

Eliza just laughed at him. 'Or perhaps I'll be a teacher

- I'll teach phonetics. I don't like your big talk and your bullying,

you see, Henry Higgins! You're not the beginning and the end!

The world will still go round without you, you know!

There'll still be rain down on that plain in Spain without you!

I can look after myself without you!'

Higgins just sat and looked at her.

'Eliza, you're wonderful! I like you to be strong like this!'

Eliza looked at him coldly, turned away and walked to the door.

'Goodbye, Professor Higgins. I won't be seeing you again.'

She went.

Higgins could not speak. He walked slowly to the door and called weakly.

'Mother! Mother!'

His mother came in. 'What is it, Henry? What's happened?'

'She's gone,' he said, almost to himself. 'What can I do?'

Where Are My Slippers?

Higgins was outside his house in Wimpole Street late that afternoon.

He couldn't stop thinking about Eliza.

Now he knew that he wanted her with him. She was part of his world.

'I've grown accustomed to her face! She almost makes the day begin.

I've grown accustomed to the tune She whistles night and noon.

Her smiles. Her frowns. Her ups, her downs, are second nature to me now;

Like breathing out and breathing in.

I was serenely independent and content before we met;

Surely I could always be that way again

- and yet I've grown accustomed to her looks;

Accustomed to her voice: Accustomed to her face.'

He stopped singing. 'Marry Freddy!' he said angrily.

'What a stupid idea! What a heartless thing to do!

She won't be happy. She'll come knocking on my door one night ...

I'm really a most forgiving man ...

but I'll never take her back! Never! Marry Freddy! Ha!'

He took his key out of his pocket but suddenly stopped.

He did not know quite what to do without Eliza.

He needed her.

He was in his work-room that evening, but he couldn't work.

He walked round and round the room.

He stopped next to his recording machine and turned it on.

Eliza's voice came out into the room.

He sat down with his back to the machine and listened, his head down.

`I want to be a lady in a flower shop,' her voice said,

'instead of selling flowers at the corner of Tottenham Court Road.

He said he could teach me, but he bullies me all the time.'

Very softly Eliza walked into the room behind him.

She stood looking at him.

`She was so wonderfully low, so terribly dirty,' Higgins said

sadly to himself, remembering her first visit to this room.

Eliza turned off the machine.

'I washed my face and hands before I came, you know,' she said.

Higgins sat up straight in his chair.

Most of all he wanted to laugh loudly, to run to her.

Instead, he sat back in the chair again,

pushed his hat down over his eyes

and very softly said, 'Eliza,where are my slippers?'

Eliza wanted to cry. She understood him so well.

The End

03

You've Got Mail

The appeal of "You've Got Mail" is as old as love and as new as the Web.

It stars Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan as immensely lovable people whose

purpose it is to display their lovability for two hours, while we desperately

yearn for them to solve their problems, fall into each other's arms and

get down to the old rumpy-pumpy.

They meet in a chat room on AOL, and soon they're revealing deep secrets

(but no personal facts) in daily and even hourly e-mail sessions.

The movie's call to arms is the inane chirp of the maddening "You've Got Mail!"

Voice (which prompts me to growl, "Yes, and I'm gonna stick it up your modem!").

But the e-mail is really just the MacGuffin--the device necessary to keep two people

who fall in love online from finding out that they already know and hate each other

in real life.

The plot surrounds Hanks and Ryan not only with e-mail lore, but with

the Yuppie Urban Lifestyle. It's the kind of movie where the characters walk

into Starbucks and we never for a moment think "product placement!" because,

frankly, we can't imagine them anywhere else.

Where the generations are so confused by modern mating appetites that Joe Fox

(the Hanks character) can walk into a bookstore with two young children and

introduce them as his brother and his aunt ("Matt is my father's son, and

Annabel is my grandfather's daughter").

Kathleen, the Meg Ryan character, runs the children's book shop she inherited

from her mother. She and her loyal staff read all the books, know all the customers,

and provide full service and love.

Joe Fox is the third generation to run a chain of gigantic book megastores.

When the new Fox Books opens around the corner from Kathleen's shop,

it's only a matter of time until the little store is forced out of business.

Kathleen turns for advice and solace to her anonymous online friend--

who is, of course, Joe.

And yet this is not quite an Idiot Plot, so called because a word from

either party would instantly end the confusion. It maintains the confusion only

up to a point, and then does an interesting thing:

allows Joe to find out Kathleen's real identity while still keeping

her quite reasonably in the dark.

And, oh, the poignant irony, as Joe has to stand there and be insulted

by the woman he loves. "You're nothing but a suit!" she says.

"That's my cue," he says. "Goodnight." And as he nobly conceals his pain,

we are solaced only by the knowledge that sooner or later the scales will fall

from her eyes.

The movie was directed by Nora Ephron, who also paired Hanks and Ryan

in "Sleepless in Seattle" (1993), and has made an emotional, if not a literal, sequel.

That earlier film was partly inspired by "An Affair to Remember," and

this one is inspired by "The Shop Around the Corner," but both are really inspired

by the appeal of Ryan and Hanks, who have more winning smiles

than most people have expressions.

Ephron and her co-writer, her sister Delia, have surrounded the characters

with cultural references that we can congratulate ourselves on recognizing:

not only Jane Austen, but also the love affair carried on by correspondence

between George Bernard Shaw and Mrs. Patrick Campbell.

Not only "The Godfather" (which "contains the answers to all of life's questions"),

but also Anthony Powell and Generalissimo Franco. (It is one of the movie's

quietly hilarious conceits that the little store's elderly bookkeeper, played

by Jean Stapleton, was in love years ago with a man who couldn't marry her

"because he had to run Spain.")

The plot I shall not describe, because it consists of nothing but itself,

so any description would make it redundant.

What you have are two people the audience desires to see together, and a lot of

devices to keep them apart. There is the added complication that both Hanks and

Ryan begin the movie with other partners (Parker Posey and Greg Kinnear

--respectively, of course).

The partners get dumped without much fuss, and then we're left with these

two lonely single people, who have neat jobs but no one to rub toes with,

and who are trapped by fate in a situation where he is destroying her dream,

and she is turning to him (without knowing it is him) for consolation. Perfect.

The movie is sophisticated enough not to make the megastore into the villain.

Say what you will, those giant stores are fun to spend time in, and there is

a scene where Kathleen ventures anonymously into Joe's big store for the first time

and looks around, at the magazine racks and the cafe and all the books

--and then there's the heartbreaking moment when she overhears a question

in the children's section, and she knows the answer but of course the clerk doesn't,

and so she supplies the answer but it makes her cry, and Joe overhears everything.

You tube:"You've Got Mail"(Best scenes)

05

Teacher's Pet (1958 film)

Journalism instructor Erica Stone asks journalist James Gannon to speak

to her night-school class. He turns down the invitation via a nasty letter to her.

His managing editor, however, orders him to accept the assignment.

He arrives late to find Stone reading aloud his letter and mocking him

in front of her class.

Humiliated, he decides to join the class as a student in order to show up

Stone and get his own back by posing as a wallpaper salesman named

Jim Gallagher.

The instructor is somewhat intrigued by this charming older man, whom

she finds an exceptional student. Gannon continues his ruse and becomes

attracted to Stone.

He finds he has to contend with Dr. Pine, as well as his own girlfriend,

Peggy DeFore, a nightclub singer (Mamie Van Doren).

When Stone discovers Gannon's deception, she immediately calls off

their relationship. Dr. Pine convinces her to give Gannon another chance.

By the end of the film, both Jim and Erica have come to understand,

and partially adopt, the other's point of view.

You Tube::Teacher's Pet

06

You tube:The Adventure of Huckfinn

What do you get when you cross America's greatest humor writer

with a runaway slave, a homeless street kid, and a lot of really

offensive language?

You get a book that's been banned in classrooms and libraries

around the country since just about the moment it was published

in the U.S. in 1885—and a book that's been on required high school

reading lists for almost as long.

Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was a follow-

up to Tom Sawyer, and it dumps us right back in the Southern antebellum

(that's "pre-war") world of Tom and his wacky adventures.

Only this time, the adventures aren't so much "wacky" as life- and

liberty-threatening.

Huckleberry Finn is a poor kid whose dad is an abusive drunk.

Huck runs away, and immediately encounters another runaway.

But this runaway isn't just escaping a mean dad;

he's escaping an entire system of racially based oppression.

This encounter throws Huckleberry into an ethical quandary

(that's a fancy way of saying "dilemma"). He knows that, legally,

he should turn in the runaway slave Jim. Problem is,

he's also starting to see Jim as a real person rather than, well,

someone's property. (Duh, Huckleberry.)

When Twain published Huckleberry Finn first in 1884 in Canada and the U.K.

and then in the U.S. in 1885, the book was immediately banned—

but not for its casual racism and use of the n-word. Nope.

It was banned because it was "vulgar," thanks to its depiction of low-class

criminals and things like Huck actually scratching himself.

Fifty years later, Huckleberry Finn was part of American literary tradition.

Both T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway thought it was one of the most

important books ever written in the U.S.—but it was still being banned,

expurgated, and rewritten to suit a (somewhat) less racist time.

Shmoop loves banned books, and not just because we're rebels.

We love banned books because a banned book means that someone's buttons

are being pressed.

And if someone's buttons are being pressed, we know that the book is raising

important issues. And boy, does Huckleberry Finn raise some important issues.

Important issues like, "Is it right to own other people?" (Hint: no.)

Important issues like, "Is it right to obey laws, if the laws are wrong?"

(Hm, this one's a little trickier.)

Important issues like, "Are individuals more important than society?"

(We don't even want to touch this question.)

Think about it this way: Huckleberry Finn suggests that the accepted moral values

of society are wrong. Public schools (and most private schools) are usually pretty

committed to sticking to accepted moral values.

Let's be clear: in most cases, those accepted moral values—don't cheat;

be respectful; show up to places on time—are hard to argue with.

But it's easy to see that schools might be a little wary about having their

students read a book that suggests individual conscience should be

a more important guide than the rules and laws that everyone follows.

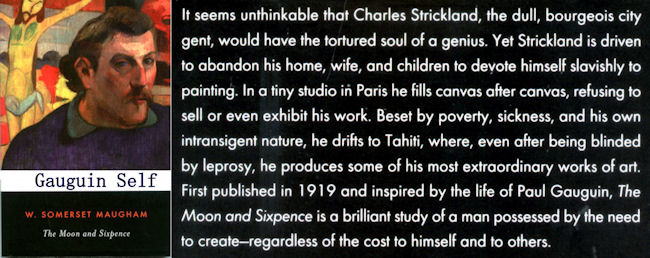

09

The Moon and Sixpence

Chapter XIX

by Somerset Maugham

I had not announced my arrival to Stroeve, and when I rang

the bell of his studio, on opening the door himself, for a moment

he did not know me. Then he gave a cry of delighted surprise and

drew me in. It was charming to be welcomed with so much

eagerness. His wife was seated near the stove at her sewing, and

she rose as I came in. He introduced me.

'Don't you remember ?' he said to her. 'I've talked to you

about him often.' And then to me: 'But why didn't you let me know

you were coming ? How long have you been here ? How long are you

going to stay ? Why didn't you come an hour earher, and we would

have dined together ?'

He bombarded me with questions. He sat me down in a chair,

patting me as though I were a cushion, pressed cigars upon me,

cakes, wine. He could not leave me alone. He was heart-broken

because he had no whisky, wanted to make coffee for me,

racked his brain for something he could possibly do for me, and

beamed and laughed, and in the exuberance of his delight sweated

at every pore.

'You haven't changed', I said, smiling, as I looked at him.

He had the same absurd appearance that I remembered. He was

a fat little man, with short legs, young still - he could not have been

more than thirty - but prematurely bald. His face was perfectly round,

and he had a very high colour, a white skin, red cheeks, and red lips.

His eyes were blue and round too, he wore large gold-rimmed

spectacles, and his eyebrows were so fair that you could not see them.

He reminded you of those jolly, fat merchants that Rubens painted.

When I told him that I meant to live in Paris for a while, and had

taken an apartment, he reproached me bitterly for not having

let him know. He would have found me an apartment himself, and

lent me furniture - did I really mean that I had gone to the expense

of buying it ? - and he would have helped me to move in. He really

looked upon it as unfriendly that I had not given him the opportunity

of making himself useful to me. Meanwhile, Mrs Stroeve sat quietly

mending her stockings, without talking, and she listened to all he said

with a quiet smile on her lips.

'So, you see, I'm married', he said suddenly; 'what do you think of

my wife?'

He beamed at her, and settled his spectacles on the bridge of his

nose. The sweat made them constantly slip down.

'What on earth do you expect me to say to that?' I laughed.

'Really, Dirk', put in Mrs Stroeve, smiling.

'But isn't she wonderful? I tell you, my boy, lose no time;

get married as soon as ever you can. I'm the happiest man alive.

Look at her sitting there. Doesn't she make a picture? Chardin,

eh ? I've seen all the most beautiful women in the world;

I've never seen anyone more beautiful than Madame Dirk Stroeve.'

'If you don't be quiet, Dirk, I shall go away.'

'Mon petit chou', he said.

She flushed a little, embarrassed by the passion in his tone.

His letters had told me that he was very much in love with his wife,

and I saw that he could hardly take his eyes off her. I could not

tell if she loved him. Poor pantaloon, he was not an object to excite

love, but the smile in her eyes was affectionate, and it was possible

that her reserve concealed a very deep feeling.

She was not the ravishing creature that his love-sick fancy saw,

but she had a grave comeliness. She was rather tall, and her grey

dress, simple and quite well-cut, did not hide the fact that her figure

was beautiful. It was a figure that might have appealed more to

the sculptor than to the costumier. Her hair, brown and abundant,

was plainly done, her face was very pale, and her features were good

without being distinguished. She had quiet grey eyes.

She just missed being beautiful, and in missing it was not even pretty.

But when Stroeve spoke of Chardin it was not without reason, and

she reminded me curiously of that pleasant house-wife in her mob-cap

and apron whom the great painter has immortalized. I could imagine her

sedately busy among her pots and pans, making a ritual of her household

duties, so that they acquired a moral significance; I did not suppose

that she was clover or could ever be amusing, but there was something

in her grave intentness which excited my interest. Her reserve was not

without mystery. I wondered why she had married Dirk Stroeve.

Though she was English, I could not exactly place her, and it was not

obvious from what rank in society she sprang, what had been her

upbringing, or how she had lived before her marriage. She was very silent,

but when she spoke it was with a pleasant voice, and her manners were

natural.

I asked Stroeve if he was working.

'Working ? I'm painting better than I've ever painted before.'

We sat in the studio, and he waved his hand to an unfinished picture

on an easel. I gave a little start. He was painting a group of Italian

peasants, in the costume of the Campagna, lounging on the steps of

a Roman church.

'Is that what you're doing now?' I asked.

'Yes. I can get my models here just as well as in Rome.'

'Don't you think it's very beautiful ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

'This foolish wife of mine thinks I'm a great artist', said he.

His apologetic laugh did not disguise the pleasure that he felt.

His eyes lingered on his picture. It was strange that his critical

sense, so accurate and unconventional when he dealt with the

work of others, should be satisfied in himself with what was

hackneyed and vulgar beyond belief.

'Show him some more of your pictures', she said.

'Shall I ?'

Though he had suffered so much from the ridicule of his friends,

Dirk Stroeve, eager for praise and naively self-satisfied, could never

resist displaying his work. He brought out a picture of two curly -

headed Italian urchins playing marbles.

'Aren't they sweet ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

And then he showed me more. I discovered that in Paris he had been

painting just the same stale, obviously picturesque things that he had

painted for years in Rome. It was all false, insincere, shoddy; and yet

no one was more honest, sincere, and frank than Dirk Stroeve.

Who could resolve the contradiction?

I do not know what put it into my head to ask:

'I say, have you by any chance run across a painter called

Charles Strickland?'

`You don't mean to say you know him ?' cried Stroeve.

'Beast', said his wife.

Stroeve laughed.

`Ma pauvre cherie.' He went over to her and kissed both her hands.

'She doesn't like him. How strange that you should know Strickland !'

'I don't like bad manners', said Mrs Stroeve.

Dirk, laughing still, turned to me to explain.

`You see, I asked him to come here one day and look at my pictures.

Well, he came, and I showed him everything I had.'

Stroeve hesitated a moment with embarrassment. I do not know

why he had begun the story against himself; he felt an awkwardness

at finishing it.

'He looked at - at my pictures, and he didn't say anything. I thought

he was reserving his judgement till the end. And at last I said:

"There, that's the lot !" He said:

"I came to ask you to lend me twenty francs."'

`And Dirk actually gave it him', said his wife indignantly.

'I was so taken aback. I didn't like to refuse. He put the money

in his pocket, just nodded, said "Thanks", and walked out.'

Dirk Stroeve, telling the story, had such a look of blank

astonishment on his round, foolish face that it was almost

impossible not to laugh.

'I shouldn't have minded if he'd said my pictures were bad,

but he said nothing - nothing.'

`And you will tell the story, Dirk', said his wife.

It was lamentable that one was more amused by the ridiculous

figure cut by the Dutchman than outraged by Strickland's

brutal treatment of him.

'I hope I shall never see him again', said Mrs Stroeve.

Stroeve smiled and shrugged his shoulders. He had already

recovered his good humour.

`The fact remains that he's a great artist, a very great artist.'

`Strickland ?' I exclaimed. 'It can't be the same man.'

'A big fellow with a red beard. Charles Strickland.

An Englishman.'

'He had no beard when I knew him, but if he has grown one

it might well be red. The man I'm thinking of only began painting

five years ago.'

'That's it. He's a great artist.'

'Impossible.'

'Have I ever been mistaken ?' Dirk asked me.

'I tell you he has genius. I'm convinced of it. In a hundred years,

if you and I are remembered at all, it will be because we knew

Charles Strickland.'

I was astonished, and at the same time I was very much

excited. I remembered suddenly my last talk with him.

'Where can one see his work ?' I asked. 'Is he having any

success ? Where is he living ?'

No; he has no success. I don't think he's ever sold a picture.

When you speak to men about him they only laugh. But I know

he's a great artist. After all, they laughed at Manet. Corot never

sold a picture. I don't know where he lives, but I can take you

to see him. He goes to a cafe in the Avenue de Clichy at seven

o'clock every evening. If you like we'll go there tomorrow.'

'I'm not sure if he'll wish to see me. I think I may remind him

of a time he prefers to forget. But I'll come all the same. Is there

any chance of seeing any of his pictures ?'

Not from him. He won't show you a thing. There's a little dealer

I know who has two or three. But you mustn't go without me;

you wouldn't understand. I must show them to you myself.'

`Dirk, you make me impatient', said Mrs Stroeve. 'How can

you talk like that about his pictures when he treated you as he

did ?' She turned to me. 'Do you know, when some Dutch people

came here to buy Dirk's pictures he tried to persuade them

to buy Strickland's. He insisted on bringing them here to show.'

'What did you think of them ?' I asked her, smiling.

`They were awful.'

`Ah, sweetheart, you don't understand.'

'Well, your Dutch people were furious with you.

They thought you were having a joke with them.'

Dirk Stroeve took off his spectacles and wiped them.

His flushed face was shining with excitement.

'Why should you think that

beauty, which is the most precious thing in the world,

lies like a stone on the beach for the careless passer-by

to pick up idly ?

Beauty is something wonderful and strange

that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world

in the torment of his soul.

And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it.

To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist.

It is a melody that he sings to you,

and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and

sensitiveness and imagination.'

`Why did I always think your pictures beautiful, Dirk ?

I admired them the very first time I saw them.'

Stroeve's lips trembled a little.

'Go to bed, my precious. I will walk a few steps with our friend,

and then I will come back.'

The End

10

You tube

God be with you till we meet again

God be with you till we meet again,

By His counsels guide, uphold you,

With His sheep securely fold you,

God be with you till we meet again.

(Refrain):

Till we meet, till we meet,

Till we meet at Jesus’ feet;

Till we meet, till we meet,

God be with you till we meet again.

God be with you till we meet again,

’Neath His wings securely hide you,

Daily manna still provide you,

God be with you till we meet again.

(Refrain):

Till we meet, till we meet,

Till we meet at Jesus’ feet;

Till we meet, till we meet,

God be with you till we meet again,

When life’s perils thick confound you,

Put His arms unfailing round you,

God be with you till we meet again.

God be with you till we meet again,

(Refrain):

Till we meet, till we meet,

Till we meet at Jesus’ feet;

Till we meet, till we meet,

God be with you till we meet again,

Keep love’s banner floating o’er you,

Smite death’s threat’ning wave before you,

God be with you till we meet again.

(Refrain):

Till we meet, till we meet,

Till we meet at Jesus’ feet;

Till we meet, till we meet,

God be with you till we meet again,

『生きる場を広げるため学び続ける仕組みを創れ』

未経験のこと、すなわち、今までやったことのないことに挑戦すると、

失敗はつきものである。従って、うまくいかないことや、挑戦失敗を、

苦にしたり、悔やんだり、悩んだりすることはない。

しかし、挑戦失敗を教訓にして、学び続けることは必要である。

学び続けることによって新しく蓄積されていく知識・情報が生きる場を

広げる力(ちから)そのものなのである。

高江常男さんが、何万回もの失敗を乗り越えて、あきらめずに、

学び続けた生き方に深い感銘を受けている。

学び続けることは最高の幸福です。

意識も頭も身体も、使わないと、どんどん錆びつく!

学び続けることは

廃用性萎縮を防ぐ最良の健康法です。

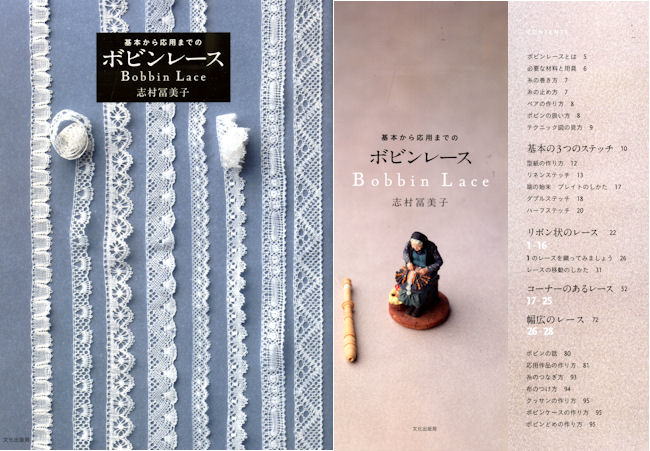

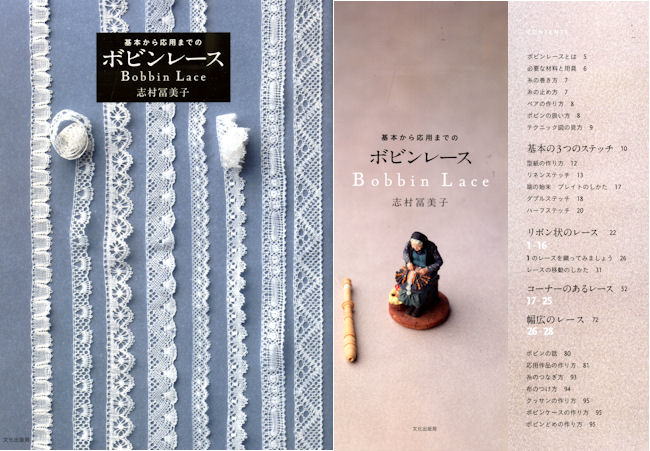

2015年12月 文化出版局 発行

志村冨美子・横浜レース教室、八王子レース教室、本郷台レース教室

TEL:045-352-7184

以上