Japan's master plan

from The Economist May18th-24th 2013

Shinzo Abe has a vision of a prosperous and patriotic Japan.

The economics looks better than the nationalism.

When Shinzo Abe resigned after just a year as prime minister,

in September 2007, he was derided by voters, broken by chronic illness,

and dogged by the ineptitude that has been the bane of so many recent

Japanese leaders.

Today, not yet five months into his second term, Mr Abe seems

to be a new man.

He has put Japan on a regime of "Abenomics", a mix of reflation,

government spending and a growth strategy designed to jolt

the economy out of the suspended animation that has gripped it

for more than two decades.

He has supercharged Japan's once-fearsome bureaucracy

to make government vigorous again.

And, with his own health revived, he has sketched out

a programme of geopolitical rebranding and constitutional change

that is meant to return Japan to what Mr Abe thinks is its rightful place

as a world power.

Mr Abe is electrifying a nation that had lost faith in its political class.

Since he was elected, the stockmarket has risen by 55%.

Consumer spending pushed up growth in the first quarter

to an annualised 3.5%.

Mr Abe has an approval rating of over 70% (compared with around

30% at the end of his first term).

His Liberal Democratic Party is poised to triumph in elections

for the upper house of the Diet in July.

With a majority in both chambers he shoilld be able to pass legislation

freely.

Pulling Japan out of its slump is a huge task. After two lost decades,

the country's nominal GDP is the same as in 1991,

while the Nikkei, even after the recent surge, is at barely a third

of its peak. Japan's shrinking workforce is burdened by the cost

of a growing number of the elderly. Its society has turned inwards

and its companies have lost their innovative edge.

Mr Abe is not the first politician to promise to revitalise hiscountry

- the land of the rising sun has seen more than its share of false

dawns - and the new-model Abe still has everything to prove.

Yet if his plans are even half successful, he will surely be counted

as a great prime minister.

The man in Japan with a plan

The reason for thinking this time might be different is China.

Economic decline took on a new reality in Japan when China elbowed

Japan aside in 2010 to become the world's second-largest economy.

As China has gained confidence, it has begun to throw its weight

around in its coastal waters and with Japan directly

over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

Earlier this month China's official People's Daily

even questioned Japanese sovereignty over Okinawa.

Mr Abe believes that meeting China's challenge means shaking off

the apathy and passivity that have held Japan in thrall for so long.

To explain the sheer ambition of his design, his people invoke

the Meiji slogan fukoku kyohei: "enrich the country, strengthen

the army". Only a wealthy Japan can afford to defend itself.

Only if it can defend itself will it be able to stand up to China - and,

equally, avoid becoming a vassal of its chief ally, the United States.

Abenomics, with its fiscal stimulus and monetary easing,

sounds as if it is an economic doctrine; in reality it is

at least as much about national security.

Perhaps that is why Mr Abe has governed with such urgency.

Within his first weeks he had announced extra government spending

worth \10.3 trillion (about $100 billion). He has appointed

a new governor of the Bank of Japan who has vowed to pump

ever more money into the financial system.

In so far as this leads to a weaker yen, it will boost exports.

If it banishes the spectre of deflation, it may also boost consumption.

But printing money can achieve only so much and, with a gross debt

of 240% of GDP, there is a limit to how much new government

spending Japan can afford.

To change the economy's long-run potential, therefore,

Mr Abe must carry through the third, structural, part of his plan.

So far, he has set up five committees charged with instigating

deep supply-side reforms. In February he surprised even his supporters

by signing Japan up to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a regional trade

agreement that promises to force open protected industries like farming.

Bad blood

Nobody could object to a more prosperous Japan that would be

a source of global demand. A patriotic Japan that had converted

its "self-defence forces" into a standing army just like any other

country's would add to the security of North-East Asia.

And yet those who remember Mr Abe's first disastrous term

in office are left with two worries.

The danger with the economy is that he goes soft, as he did before.

Already there are whispers that, if second-quarter growth is poor,

he will postpone the first of two consumption-tax increases due

in 2024-15 for fear of strangling the recovery.

Yet a delay would leave Japan without a medium-term plan

for limiting its debt and signal Mr Abe's unwillingness to face up

to tough choices.

The fear is that he will bow to the lobbies that resist reform.

Agriculture, pharmaceuticals and electricity are only some of

the industries that need to be exposed to competition.

Mr Abe must not shrink from confronting them, even though

that means taking on parts of his own party.

The danger abroad is that he takes too hard a line, confusing

national pride with a destructive and backward-looking nationalism.

He belongs to a minority that has come to see Japan's post-war

tutelage under America as a humiliation. His supporters insist

he has learned that minimising Japan's war-time guilt is unacceptable.

And yet he has already stirred up ill will with China and South Korea

by asking whether imperial Japan (for which his grandfather helped

run occupied Manchuria) really was an aggressor, and by allowing

his deputy to visit the Yasukuni shrine, where high-ranking war

criminals are honoured among Japan's war dead.

Besides, Mr Abe also seems to want more than the standing army

Japan now needs and deserves. The talk is of an overhaul of

the liberal parts of the constitution, unchanged since it was handed

down by America in 1947, Mr Abe risks feeding regional rivalries,

which could weaken economic growth by threatening trade.

Mr Abe is right to want to awaken Japan. After the upper-house

elections, he will have a real chance to do so. The way to restore

Japan is to focus on reinvigorating the economy, not to end up

in a needless war with China.

The End

001-2

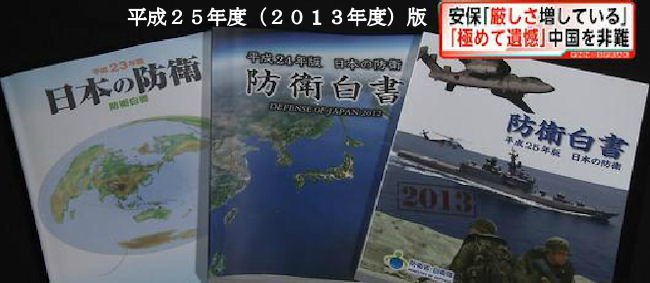

Defense paper: Chinese ships of grave concern

July 9,2013

Japan's annual defense report expresses grave concern

about the expansion of China's naval activities

around the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

This year's white paper on defense policy was submitted to

a Cabinet meeting on Tuesday.

The report says that Chinese government ships have frequently

entered Japanese waters around the Senkaku Islands.

The islands are controlled by Japan, but also claimed by China and

Taiwan. The report warns that some actions by the ships were so

dangerous that they could have caused emergency situations.

The white paper says China insists on its own stories

that are inconsistent with existing international law and

its expanding maritime activity is of concern to the region

and the international community.

On the issue of North Korea's ballistic missile development,

the report says that the North demonstrated technological

advances with the launch in December last year.

It warns that North Korean missiles are a real and imminent threat

to the international community. They are believed to have enough

range to reach the US west coast and even the central states.

The white paper also expresses concern about the suspected

involvement of Chinese, Russian and North Korean government

organizations in cyber attacks targeting the governments of

other countries.

The End

002

Useful Phrases in a Meeting

1.

I need to notify you about a merger plan. I know

this comes as a surprise to you, but it's some-

thing we need to do for the survival of the company.

2.

I need to inform you that, based on your performance

last year, your salary is being reduced

by three percent. I know you're disappointed, but

we have to follow company policy.

3.

I'm afraid I have to inform you about some

changes in our long-term plan. Today I'd like to

outline the changes for you.

4.

I'd like to give you an update on the sales figures

for our new computer model. Sales rose by 10 percent

last month.

5.

There're going to be some changes in the long-term

plan. Listen carefully and don't miss anything,

6.

There's going to be a merger I need to tell you

about. It's not the best thing to happen, but at least

the company will survive.

7.

There are a few announcements I need to make.

First, we've decided to change our policy concerning

vacation time.

8.

By way of announcements, I'm happy to report

that our sales last month increased by 10 percent

over the same month in the previous year.

9.

You might be interested to know that ABC's new

computer will be coming out in June. From what

I've heard, it's very similar to our B3 Model.

10.

Mary, could you give us an update on the current

sales strategy? We'd also like to know how

effective you think it is.

11.

Mary will now update us on the progress we're

making with the current sales strategy. She'll also

give us her evaluation of its effectiveness.

12.

I'd like to make a suggestion, if I may.

Why don't we just rent an office for two months

while making repairs ?

If I'm not mistaken, that will save us time and money.

13.

This is my suggestion. We rent an office for two months

while we make repairs on this building.

That way we can maintain productivity and save money.

14.

We need to find an office to rent for two months.

Then, when the repairs are done on this building

we can move back in.

It's the only way we can stay productive and save money.

15.

Do you think it would be appropriate to make some

suggestions ?

I think I know of a way that we can cut our costs and

also increase efficiency.

16.

What do you think about that suggestion ?

Is the amount of money and time we'll save really

significant ?

17

I have a feeling that this is the best plan. In order to be

more certain, we need to do some more studies.

18

I strongly believe that this policy is wrong. It's wrong

for several reasons. One of them is that it hurts

employee morale.

19

I know there are other viewpoints, but I am willing

to stake my reputation on this.

20

I can't say I know for certain, but I am quite sure

about this.

21

I'm not sure, but I think that this plan will work.

I think we won't know for sure unless we implement it.

22

I guess this plan is the best. Nothing is certain,

but it seems the best to me.

23

Based on the information I have, I would say that

this Is the best plan. Why don't we try it and

see what happens ?

24

I have a firm belief that what I am saying is true.

It'll only be a matter of time before you'll agree

with me.

25

I think everyone will agree with me on this.

It's really the best plan of action.

26

I have to think that this plan is the best.

Why don't we give it a try and see what happens ?

27

I don't just think, I know that this is a good idea.

I can't see anything wrong with it.

28

I have no doubts that this will work.

It's our very best option at this time.

29

If you ask me, I think that we need to change

the dress code. We don't need to wear a suit

if we're not going to meet with clients.

30

If you want my opinion, the dress code is outdated.

If I were in charge, then we'd change the dress code.

31

My personal opinion is that the dress code is

too strict. I don't know why we can't dress casually

when we aren't going to be meeting with crents.

32

Maybe it's just my opinion, but I kind of think

we should change the dress code.

33

This policy hurts employee morale. That's just

one of the reasons why I think it's wrong.

34

This is just an opinion, but I think this plan is

our best option. Let's try it and see if it works.

35

I'd like to ask for everyone's opinion on this.

We want to have everything on the table.

36

I'd like to know what you think about George

Green, the new consultant. Do you think he's

really as good as everyone thinks ?

37

I'd like to ask you about something.

What do you think about George Green ?

38

I'd like you to look at the graph on page 5.

This shows how sales have fluctuated

over the past six months.

39

I've prepared a graph on page 5 showing sales

trends since April of this year. From this graph

we can see that sales are slowly dropping.

40

The obvious reason is money. We've already used up

most our budget for the current fiscal year.

41

There are several reasons. For one thing,

we only have a limited budget.

42

There're lots of reasons why we can't do this right now.

The biggest one is that we don't have the money.

We have to stay within our budget.

43

Let me just say that we are running out of money.

This leads me to think that now is not the right time

to start something new.

44

Now, let's look at the table that shows the sales trends

of our competitors. I'd like to ask you to go to page 5

of the handouts.

45

If I may, I'd like to ask you about the new consultant,

George Green. Is he doing what we want him to be doing ?

46

If you look on page 5 of the handout, you can see

the trend in sales for the last six months.

47

George Green doesn't seem to be producing any results.

Am I right or maybe I'm not seeing the whole picture ?

48

Off the record, what do you think about George Green ?

Do you think he's doing what he said he would do ?

49

Could you look now at page 5 of the handout ?

This is a graph of sales trends starting from April.

50

The next sheet is a graph showing sales for the last six

months. As you can see, sales have been rising steadily.

51

The project seems to be going well.

I think we can expect some good results.

52

I'm starting to have some doubts about this project.

I think we're going to be disappointed with the results.

53

I'm affaid I don't know what's going to happen

with this project. It's too early to evaluate it.

54

Let's think about what's going to happen if this

project doesn't go well. Do we have a plan B ?

55

I can already tell that this plan is not going to work.

I think we need to take action right now to limit the cost.

56

I'm not a fortuneteller, but I think our forecast is

going to be right. We still have a lot of work to do,

but I'm optimistic.

57

I've got to ask, is the situation getting better or worse ?

58

Just a quick question. Will the problem get better or worse

in the next six months ?

59

I really need to ask you something. Six months from now,

is the situation going to be better or worse?

60

I'd like to ask you a two-part question.

First, how long have you known about the problem ?

And second, what's being done about the problem now ?

61

Here're a couple questions for you.

When did you become aware of this problem ?

And what's being done to fix it now ?

62

Could you give me some more specific information

about what caused the problem ?

63

So you think that delaying the launch will give you

more time to launch an effective ad campaign ?

64

So you're telling me that you want two extra months

for the pre-launch ad campaign ?

65

Let me make sure I have this right. The consultant

recommends putting off the launch by two months,

and you agree with him ?

66

I want to make sure I understand you. You and

the consultant want to delay the launch by two months.

67

Is my understanding correct that you and the consultant

think the best strategy is to delay the launch ?

68

Are you sure that putting off the launch is the best thing ?

Do you really think that you could do a better job ?

(to be continued)

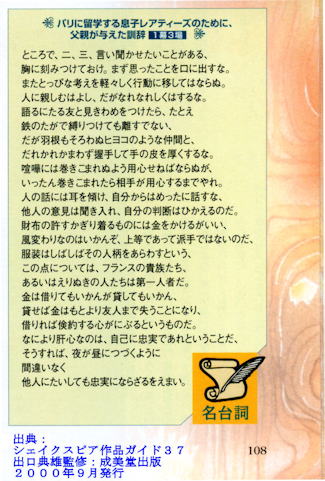

003

Hamlet

by William Shakespeare

Scene III

Elsinore. The house of Polonius.

[Enter LAERTES and OPHELIA his sister.]

Laertes

My necessaries are embark'd. Farewell. And,

sister, as the winds give benefit

And convoy is assistant, do not sleep,

But let me hear from you.

Ophelia

Do you doubt that?

Laertes

For Hamlet, and the trifling of his favour,

hold it a fashion and a toy in blood,

a violet in the youth of primy nature,

forward not permanent, sweet not lasting,

the perfume and suppliance of a minute;

no more.

Ophelia

No more but so?

Laertes

Think it no more;

for nature crescent does not grow alone.

In thews and bulk, but as this temple waxes,

the inward service of the mind and soul

grows wide withal.

Perhaps he loves you now,

and now no soil nor cautel doth besmirch

the virtue of his will; but you must fear,

his greatness weigh'd, his will is not his own;

for he himself is subject to his birth:

he may not, as unvalued persons do,

carve for himself; for on his choice depends

the sanity and health of this whole state;

and therefore must his choice be circumscrib'd

unto the voice and yielding of that body

whereof he is the head.

Then if he says he loves you,

it fits your wisdom so far to believe it

as he in his particular act and place

may give his saying deed; which is no further

than the main voice of Denmark goes withal.

Then weigh what loss your honour may sustain,

if with too credent ear you list his songs,

or lose your heart, or your chaste treasure open

to his unmast'red importunity.

Fear it, Ophelia, fear it, my dear sister;

and keep you in the rear of your affection,

out of the shot and danger of desire.

The chariest maid is prodigal enough

if she unmask her beauty to the moon.

Virtue itself scapes not calumnious strokes;

the canker galls the infants of the spring

too oft before their buttons be disclos'd;

and in the morn and liquid dew of youth

contagious blastments are most imminent.

Be wary, then; best safety lies in fear:

Youth to itself rebels, though none else near.

Ophelia

I shall the effect of this good lesson keep

as watchman to my heart.

But, good my brother, do not, as some ungracious

pastors do.

Show me the steep and thorny way to heaven,

whiles, like a puff'd and reckless libertine.

Himself the primrose path of dalliance treads

and recks not his own rede.

Laertes

0, fear me not !

[Enter POLONIUS.]

I stay too long. But here my father comes.

A double blessing is a double grace;

Occasion smiles upon a second leave.

Polonius

Yet here, Laertes! Aboard, aboard, for shame !

The wind sits in the shoulder of your sail,

and you are stay'd for. There - my blessing

with thee !

And these few precepts in thy memory

look thou character.

Give thy thoughts no tongue,

Nor any unproportion'd thought his act.

Be thou familiar, but by no means vulgar.

Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried,

grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel;

But do not dull thy palm with entertainment

of each new-hatch'd, unfledg'd courage.

Beware of entrance to a quarrel;

but, being in, bear't that th' opposed may beware of thee.

Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice;

take each man's censure, but reserve thy judgment.

Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy,

but not express'd in fancy; rich, not gaudy;

for the apparel oft proclaims the man;

and they in France of the best rank and station

are of a most select and generous choice in that.

Neither a borrower nor a lender be;

for loan oft loses both itself and friend,

and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

This above all - to thine own self be true,

and it must follow, as the night the day,

thou canst not then be false to any man.

Farewell; my blessing season this in thee !

Laertes

Most humbly do I take my leave, my lord.

Polonius

The time invite's you; go, your servants tend.

Laertes

Farewell, Ophelia; and remember well

what I have said to you.

Ophelia

'Tis in my memory lock'd,

and you yourself shall keep the key of it.

Laertes

Farewell.

[Exit.]

The End

004

The Moon and Sixpence

by Somerset Maugham

Chapter XIX

I had not announced my arrival to Stroeve, and when I rang

the bell of his studio, on opening the door himself, for a moment

he did not know me. Then he gave a cry of delighted surprise and

drew me in. It was charming to be welcomed with so much

eagerness. His wife was seated near the stove at her sewing, and

she rose as I came in. He introduced me.

'Don't you remember ?' he said to her. 'I've talked to you

about him often.' And then to me: 'But why didn't you let me know

you were coming ? How long have you been here ? How long are you

going to stay ? Why didn't you come an hour earher, and we would

have dined together ?'

He bombarded me with questions. He sat me down in a chair,

patting me as though I were a cushion, pressed cigars upon me,

cakes, wine. He could not leave me alone. He was heart-broken

because he had no whisky, wanted to make coffee for me,

racked his brain for something he could possibly do for me, and

beamed and laughed, and in the exuberance of his delight sweated

at every pore.

'You haven't changed', I said, smiling, as I looked at him.

He had the same absurd appearance that I remembered. He was

a fat little man, with short legs, young still - he could not have been

more than thirty - but prematurely bald. His face was perfectly round,

and he had a very high colour, a white skin, red cheeks, and red lips.

His eyes were blue and round too, he wore large gold-rimmed

spectacles, and his eyebrows were so fair that you could not see them.

He reminded you of those jolly, fat merchants that Rubens painted.

When I told him that I meant to live in Paris for a while, and had

taken an apartment, he reproached me bitterly for not having

let him know. He would have found me an apartment himself, and

lent me furniture - did I really mean that I had gone to the expense

of buying it ? - and he would have helped me to move in. He really

looked upon it as unfriendly that I had not given him the opportunity

of making himself useful to me. Meanwhile, Mrs Stroeve sat quietly

mending her stockings, without talking, and she listened to all he said

with a quiet smile on her lips.

'So, you see, I'm married', he said suddenly; 'what do you think of

my wife?'

He beamed at her, and settled his spectacles on the bridge of his

nose. The sweat made them constantly slip down.

'What on earth do you expect me to say to that?' I laughed.

'Really, Dirk', put in Mrs Stroeve, smiling.

'But isn't she wonderful? I tell you, my boy, lose no time;

get married as soon as ever you can. I'm the happiest man alive.

Look at her sitting there. Doesn't she make a picture? Chardin,

eh ? I've seen all the most beautiful women in the world;

I've never seen anyone more beautiful than Madame Dirk Stroeve.'

'If you don't be quiet, Dirk, I shall go away.'

'Mon petit chou', he said.

She flushed a little, embarrassed by the passion in his tone.

His letters had told me that he was very much in love with his wife,

and I saw that he could hardly take his eyes off her. I could not

tell if she loved him. Poor pantaloon, he was not an object to excite

love, but the smile in her eyes was affectionate, and it was possible

that her reserve concealed a very deep feeling.

She was not the ravishing creature that his love-sick fancy saw,

but she had a grave comeliness. She was rather tall, and her grey

dress, simple and quite well-cut, did not hide the fact that her figure

was beautiful. It was a figure that might have appealed more to

the sculptor than to the costumier. Her hair, brown and abundant,

was plainly done, her face was very pale, and her features were good

without being distinguished. She had quiet grey eyes.

She just missed being beautiful, and in missing it was not even pretty.

But when Stroeve spoke of Chardin it was not without reason, and

she reminded me curiously of that pleasant house-wife in her mob-cap

and apron whom the great painter has immortalized. I could imagine her

sedately busy among her pots and pans, making a ritual of her household

duties, so that they acquired a moral significance; I did not suppose

that she was clover or could ever be amusing, but there was something

in her grave intentness which excited my interest. Her reserve was not

without mystery. I wondered why she had married Dirk Stroeve.

Though she was English, I could not exactly place her, and it was not

obvious from what rank in society she sprang, what had been her

upbringing, or how she had lived before her marriage. She was very silent,

but when she spoke it was with a pleasant voice, and her manners were

natural.

I asked Stroeve if he was working.

'Working ? I'm painting better than I've ever painted before.'

We sat in the studio, and he waved his hand to an unfinished picture

on an easel. I gave a little start. He was painting a group of Italian

peasants, in the costume of the Campagna, lounging on the steps of

a Roman church.

'Is that what you're doing now?' I asked.

'Yes. I can get my models here just as well as in Rome.'

'Don't you think it's very beautiful ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

'This foolish wife of mine thinks I'm a great artist', said he.

His apologetic laugh did not disguise the pleasure that he felt.

His eyes lingered on his picture. It was strange that his critical

sense, so accurate and unconventional when he dealt with the

work of others, should be satisfied in himself with what was

hackneyed and vulgar beyond belief.

'Show him some more of your pictures', she said.

'Shall I ?'

Though he had suffered so much from the ridicule of his friends,

Dirk Stroeve, eager for praise and naively self-satisfied, could never

resist displaying his work. He brought out a picture of two curly -

headed Italian urchins playing marbles.

'Aren't they sweet ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

And then he showed me more. I discovered that in Paris he had been

painting just the same stale, obviously picturesque things that he had

painted for years in Rome. It was all false, insincere, shoddy; and yet

no one was more honest, sincere, and frank than Dirk Stroeve.

Who could resolve the contradiction?

I do not know what put it into my head to ask:

'I say, have you by any chance run across a painter called

Charles Strickland?'

`You don't mean to say you know him ?' cried Stroeve.

'Beast', said his wife.

Stroeve laughed.

`Ma pauvre cherie.' He went over to her and kissed both her hands.

'She doesn't like him. How strange that you should know Strickland !'

'I don't like bad manners', said Mrs Stroeve.

Dirk, laughing still, turned to me to explain.

`You see, I asked him to come here one day and look at my pictures.

Well, he came, and I showed him everything I had.'

Stroeve hesitated a moment with embarrassment. I do not know

why he had begun the story against himself; he felt an awkwardness

at finishing it.

'He looked at - at my pictures, and he didn't say anything. I thought

he was reserving his judgement till the end. And at last I said:

"There, that's the lot !" He said:

"I came to ask you to lend me twenty francs."'

`And Dirk actually gave it him', said his wife indignantly.

'I was so taken aback. I didn't like to refuse. He put the money

in his pocket, just nodded, said "Thanks", and walked out.'

Dirk Stroeve, telling the story, had such a look of blank

astonishment on his round, foolish face that it was almost

impossible not to laugh.

'I shouldn't have minded if he'd said my pictures were bad,

but he said nothing - nothing.'

`And you will tell the story, Dirk', said his wife.

It was lamentable that one was more amused by the ridiculous

figure cut by the Dutchman than outraged by Strickland's

brutal treatment of him.

'I hope I shall never see him again', said Mrs Stroeve.

Stroeve smiled and shrugged his shoulders. He had already

recovered his good humour.

`The fact remains that he's a great artist, a very great artist.'

`Strickland ?' I exclaimed. 'It can't be the same man.'

'A big fellow with a red beard. Charles Strickland.

An Englishman.'

'He had no beard when I knew him, but if he has grown one

it might well be red. The man I'm thinking of only began painting

five years ago.'

'That's it. He's a great artist.'

'Impossible.'

'Have I ever been mistaken ?' Dirk asked me.

'I tell you he has genius. I'm convinced of it. In a hundred years,

if you and I are remembered at all, it will be because we knew

Charles Strickland.'

I was astonished, and at the same time I was very much

excited. I remembered suddenly my last talk with him.

'Where can one see his work ?' I asked. 'Is he having any

success ? Where is he living ?'

No; he has no success. I don't think he's ever sold a picture.

When you speak to men about him they only laugh. But I know

he's a great artist. After all, they laughed at Manet. Corot never

sold a picture. I don't know where he lives, but I can take you

to see him. He goes to a cafe in the Avenue de Clichy at seven

o'clock every evening. If you like we'll go there tomorrow.'

'I'm not sure if he'll wish to see me. I think I may remind him

of a time he prefers to forget. But I'll come all the same. Is there

any chance of seeing any of his pictures ?'

Not from him. He won't show you a thing. There's a little dealer

I know who has two or three. But you mustn't go without me;

you wouldn't understand. I must show them to you myself.'

`Dirk, you make me impatient', said Mrs Stroeve. 'How can

you talk like that about his pictures when he treated you as he

did ?' She turned to me. 'Do you know, when some Dutch people

came here to buy Dirk's pictures he tried to persuade them

to buy Strickland's. He insisted on bringing them here to show.'

'What did you think of them ?' I asked her, smiling.

`They were awful.'

`Ah, sweetheart, you don't understand.'

'Well, your Dutch people were furious with you.

They thought you were having a joke with them.'

Dirk Stroeve took off his spectacles and wiped them.

His flushed face was shining with excitement.

'Why should you think that

beauty, which is the most precious thing in the world,

lies like a stone on the beach for the careless passer-by

to pick up idly ?

Beauty is something wonderful and strange

that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world

in the torment of his soul.

And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it.

To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist.

It is a melody that he sings to you,

and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and

sensitiveness and imagination.'

`Why did I always think your pictures beautiful, Dirk ?

I admired them the very first time I saw them.'

Stroeve's lips trembled a little.

'Go to bed, my precious. I will walk a few steps with our friend,

and then I will come back.'

The End

005

The KAIZEN Approach to Problem Solving

『KAIZEN』 Chapter 6

by Masaaki Imai

The Problem in Management

KAIZEN starts with a problem or, more precisely, with the

recognition that a problem exists. Where there are no problems,

there is no potential for improvement. A problem in business

is anything that inconveniences people downstream, either

people in the next process or ultimate customers.

The problem is that the people who create the problem are

not directly inconvenienced by it. Thus people are always

sensitive to problems (or inconveniences created by problems)

caused by other people, yet insensitive to the problems and

the inconveniences they cause other people. The best way

to break the vicious circle of passing the buck from one person

to another is for every individual to resolve never to pass on

a problem to the next process.

In day-to-day management situations, the first instinct,

when confronted with a problem, is to hide it or ignore it

rather than to face it squarely. This happens because a problem

is a problem, and because nobody wants to be accused of

having created the problem. By resorting to positive thinking,

however, we can turn each problem into a valuable opportunity

for improvement. Where there is a problem, there is potential

for improvement. The starting point in any improvement, then,

is to identify the problem. There is a saying among TQC

practitioners in Japan that problems are the keys to hidden

treasure. Yet how many people have the courage to admit that

they have a problem?

I still vividly recall my first sales call twenty-some years ago.

I had just gotten back from a five-year stint with the Japan

Productivity Center in the United States, had hung out my shingle

as a management consultant, and was enthusiastically calling on

prospective clients.

My first call was on Revlon Japan. I had an introduction from

an executive at the head office in New York and had been told that

their man in Tokyo needed some assistance. So, as a novice in the

consulting business, I made a sweeping entrance into the general

manager's office and, as soon as I had introduced myself, started

with, "With regard to your problems in Japan ..." The American

general manager cut me off with a curt, "We have no problems in

Japan." End of interview. I have since become wiser and now never

discuss a client's "problem." It is always the client's

"opportunity for improvement."

It is only human nature not to want to admit that you have

a problem, since admitting to problems is tantamount to confessing

failings or weaknesses. The typical American manager is afraid

people will think he is part of the problem. However, once he

realizes that he has a problem (as most people do), his first

step should be to admit it and to "share" the problem. It is

particularly important that he share the problem with his superiors,

since he usually does not have the resources to solve it alone

and will need company support.

The worst thing a person can do is to ignore or cover up

a problem. When a worker is afraid that his boss will be mad at him

if he finds out a machine is malfunctioning, he may keep on making

the defective parts and hope that nobody will notice. However,

if he is courageous enough, and if his boss is supportive enough,

they may be able to identify the problem and solve it.

A very popular term in Japanese TQC activities is warusa-kagen,

which refers to things that are not really problems but are somehow

not quite right. Left unattended, warusa-kagen may eventually

develop into serious trouble and may cause substantial damage.

In the workplace, it is usually the worker, not the supervisor,

who notices the warusa-kagen.

In the TQC philosophy, the worker must be encouraged to identify

and report such warusa-kagen to the boss, who should welcome

the report. Rather than blame the messenger, management should be glad

the problem was pointed out while it was still minor and should welcome

the opportunity for improvement. In reality,however, many opportunities

are lost simply because neither worker nor management likes problems.

Another point in warusa-kagen is that the problems must be expressed

in quantitative, not qualitative, terms. Many people are uncomfortable

with the effort to quantify. Yet only by analyzing problems in terms

of objective figures can we tackle them in a realistic manner.

When workers are trained to be attentive to warusa-kagen, they also

become attentive to subtle abnormalities developing in the work-shop.

In one Tokai Rika plant, workers reported 534 such subtle abnormalities

in a single year. Some of these irregularities might have led to serious

trouble had they not been brought to management's attention.

Another important aspect of this approach to problems is that most

problems in management occur in cross-functional areas. Good Japanese

managers who have worked at the same company for years and expect

to stay for years more have developed a sensitivity to cross-functional

situations.

(Promotion to important managerial positions should in part be based on

how much sensitivity to cross-functional requirements the employee

develops.)

Information feedback and coordination with other departments is a routine

part of a manager's job.

In many Western companies, however, cross-functional situations are

perceived as conflicts and are addressed from the standpoint of conflict

resolution rather than problem solving. The lack of predetermined criteria

for solving cross-functional problems and the jealously guarded professional

"turf' make the job of solving cross-functional problems all the more

difficult.

KAIZEN and Labor-Management Relations

This may be an appropriate point at which to consider the role

Western trade unions have traditionally played with regard to improvement.

If we take an unbiased look at what unions have been doing in the name

of protecting their members' rights, we find that they have, by obstinately

opposing change, often succeeded only in depriving their members of a chance

for fulfillment, a chance to improve themselves.

By resisting change in the workplace, unions have deprived the workers

of a chance to work better and more efficiently on an improved process

or machine. Workers should welcome being exposed to new skills and

opportunities, because such experience leads to new horizons and challenges

in life. However, when management has suggested such changes as assigning

workers different jobs, the unions have opposed it, arguing that it would lead

to exploitation and would infringe upon the workers' union rights.

Stubbornly preserving the tradition of union membership based upon

particular job skills, union members have been confined to their fragmented

pieces of work and have forfeited precious opportunities to learn and acquire

new skills associated with their work-opportunities to meet new challenges

and to grow as human beings. Such an attitude has often been based on the

union's fear that improvements may result in a decline in membership or

unemployment for its members.

In May 1982, Hajime Karatsu, then managing director of Matsushita

Communication Industrial, gave an address in Washington,D.C., explaining

Japan's successful TQC practices. After this speech, someone asked him

if he thought there was a culture gap between Japan and the United States

that made TQC possible in Japan but not in the United States. Karatsu's

response was:

Before coming to Washington, I stopped off in Chicago to see the Consumer

Electronics Show. There were many Matsushita products on display at the show.

When they arrived packed in crates, it was the work of the carpenters' union

to remove nails from the crates. However, simply taking out the nails was not

enough to remove the entire wooden frame, since there were some nuts and bolts

remaining. The man from the carpenters' union said that it was not his job

to remove the nuts and bolts, and that he would not do it. Finally the frames

were removed, but again the work stopped because the rest had to be done

by a worker from another union. Then we learned that pamphlets ordered from

Japan had arrived. I went to see about them, but there was nobody there from

the right union to unload the packages. We waited for two hours, but no one

showed up. Finally, the truck driver who had delivered the packages gave up

and went back, with the pamphlets still in his truck.

It might seem that there is a cultural pattern here that makes it

impossible to cooperate to get the job done. However, baseball is a very

American game, and I have never seen the first basemen's and second basemen's

unions discussing who should field the ball after the batter hits it. Whoever

can do it does it, and the whole team benefits. In Japanese companies, people

try to achieve the same type of teamwork as on a baseball team.

In 1965, Isetan Department Store, one of the largest department stores

in Japan (6,000 employees), moved to a five-day week for all employees.

At the same time, labor and management agreed that one of the days off should

be used for rest and the other for self-improvement. In fact, a joint

declaration on Isetan's manpower resources development policy was issued

by the company president and the union president. It read:

The Isetan management and union hereby declare that, sharing the same

workplace, we will join hands to develop our natural personalities and

capabilities to the fullest extent in our daily life and to create

an environment conducive to development. The underlying philosophy of this

joint declaration was that

(1) an individual's developing and exercising his skills at work benefits

both the company and the individual and

(2) people are constantly seeking self-improvement, and the real meaning

of equal opportunity is to provide opportunities for growth.

Stealing Jobs

People who are interested in improving their work should take a positive

interest in the upstream processes that provide the material or semifinished

products. They should also take an interest in the downstream processes,

regarding them as their customers and making every effort to pass along only

good materials or products.

As the old saw goes, "You cannot make a good omelette out of rotten eggs."

There is a similar correlation between the individual's job and the jobs of

his co-workers: if one worker is interested in making KAIZEN part of his work,

his fellow workers must also be involved.

Any job involving more than one worker has gray areas that do not belong

to any one individual. Such gray areas must be taken care of by whoever is

at hand. When the worker sticks to his own job description and refuses

to do any more than what is formally required of him, there is little hope

of KAIZEN.

The Japanese worker has been noted for his willingness to take care of

such gray areas. Because of the lifetime-employment system, the Japanese

blue-collar worker does not feel threatened even when other people pitch in

and do part of his job, since it affects neither his income nor his job

security. For the same reason, he is willing to teach workers the skills

that he has acquired on the job. This smooth transfer of skills from one

generation of workers to another has consolidated the solid base of skilled

labor in Japanese industry.

In an environment where job descriptions and manuals dictate every action,

there is little flexibility for workers to engage in such "gray area"

activities. The workers should be trained so that they can work flexibly

in these gray areas, even as they strictly follow the established work

standards in performing the job. Flexibility is further reduced when several

craft unions are involved in the same workplace. In such a case, going too

far into a gray area can easily be construed as "stealing the other guy's

job." In Japan, this would not be stealing but would be a positive and

humane contribution to KAIZEN, viewed as being to everyone's advantage.

There is something dehumanizing about the logic that the only way you can

be assured of a job is to refuse to teach anyone else your skills. We must

create an environment in which improvement is everybody's business and

everyone's concern.

The End

006

The Good Earth

by Pearl S. Buck

1.The Plot

Pearl Buck's The Good Earth opens with Wang Lung,

a poor Chinese farmer, making the preparations for his wedding day.

To mark the momentous change in his life, he bathes for the first time

since the New Year, dresses in his best clothes, and buys extra food

at the market.

He goes to the House of Hwang, where his new wife has worked

as a slave, to collect her. Although his new wife, 0-lan, is not beautiful,

and her feet have not been bound, he is pleased that she has neither

pockmarks nor a split lip. Back at his modest house he hosts a wedding

feast, and she impresses him with her cooking skills, making a meal more

delicious than Wang has ever tasted.

Wang's marriage brings good fortune. 0-lan's arrival restores order and

comfort to the house; she works hard in the fields and soon gives birth

to a son. Wang's crops are plentiful, and when the New Year arrives,

0-lan and Wang take their son to the Great House (the House of Hwang),

where 0-lan presents her healthy son to her former mistress.

Because of their good fortune, Wang has enough silver to buy land from

the Great House, which has fallen on hard times. For several more years,

Wang and 0-lan thrive. 0-lan brings a second son and a daughter into

the world, and Wang continues to buy land from the increasingly decadent

House of Hwang.

Their luck turns, however, with the beginning of a severe drought.

Starvation drives them to desperate measures and sets the villagers

at each other's throats. Finally Wang and his family head south for the city,

where there is the promise of food, using the last of their money to buy

railroad passage.

Life in the city brings little improvement - but at least there is food.

Wang, his wife, his father, and their three children live in a shack and buy

their meals for pennies in the great public kitchens of the city. Wang pulls

a rick-shaw, and 0-lan and her children beg for money. Wang dreams

constantly of returning to the land. Finally a war breaks out in the city,

the wealthy families flee, and by stealing from the rich, Wang and 0-lan

are able to return to their land and rebuild their farm.

The family's fortunes improve and more children are born. Despite a flood

that submerges his fields, Wang's financial power increases. He grows

restless and dissatisfied with his wife and falls under the spell of a woman

called Lotus Flower, who becomes his concubine. But Lotus Flower does

not bring him happiness, and Wang is plagued by turmoil in his household.

Both 0-lan and his father die, and his sons lack interest in the rural

empire he has built. In the end, it is clear that his obsession with the land

will not outlive him, and all he has worked to build will disappear after his

death.

2.Characters

Wang Lung

A poor farmer at the beginning and a wealthy landowner by the end

of the novel, Wang holds steadfast to the belief that everything comes

from the good earth. He is not immune to earthy temptations, and

he allows his sons to become further and further removed from their

agricultural roots, but working the land always helps to restore him.

0-lan

The stoic, hardworking, and self-sacrificing wife of Wang Lung.

Formerly a slave in the Great House, she is extremely proud that she

has married and brought sons into her husband's family. A woman of

few words, she is thoughtful, persuasive, and wise. Wang begins to

appreciate her value only after her death.

Wang Lung's Father

An infirm old man who wants nothing more than to have a cup of hot

water in the morning and grandsons to warm his heart, Wang Lung's

father has few responsibilities. He refuses to beg in the great city, and

he does not help with the farmwork. He does, however, greatly disapprove

of his son's having taken a concubine.

Wang Lung's Oldest Son

Educated, moody, and overly concerned with the social standing of the

family, Wang Lung's oldest son exhibits all of the characteristics of the

privileged class. He takes great pride in restoring the House of Hwang -

and spending the family money freely.

Wang Lung's Oldest Daughter

Referred to as the "poor fool," the oldest daughter was born before

the famine and appears to suffer from mental disabilities. Though Wang

Lung initially resents her, he grows very fond of her.

Wang Lung's Second Son

Wang Lung's second son is frugal and practical. He receives an education,

becomes a merchant, and oversees the business side of his father's farms.

He chooses a wife from a farming family; he also reaffirms his differences

from his brother.

Wang Lung's Uncle

Lazy and corrupt, Wang Lung's uncle borrows money from his nephew,

attempts to swindle him out of his land, and eventually moves his family

into Wang Lung's house. His association with notorious robbers allows him

to manipulate Wang, but his power wanes when he becomes addicted to

opium.

Wang Lung's Aunt

The opposite of 0-lan, Wang Lung's aunt possesses no domestic skills

and allows her children to run wild. She helps arrange for Lotus Flower

to move into Wang Lung's house. Like her husband, she succumbs to opium.

Wang Lung's Nephew

A rebellious young man with unwholesome appetites. He joins the army.

Lotus Flower

Dainty and withholding, Lotus Flower works as a prostitute in a teahouse,

where she casts a spell over Wang Lung. Later she becomes his much-

spoiled concubine.

3.Questions for Discussion

When The Good Earth was published, some critics called it a universal

story. Is the story of The Good Earth still universal at the beginning of

the twenty-first century? What is a "universal story"?

Pearl Buck was an early advocate for women's rights and feminism.

How are women depicted in The Good Earth ? In what ways, if any,

do you see feminist beliefs at work in this novel?

Do the events that unfold in The Good Earth make its title a true

statement or an ironic one ? Is the earth really good or not ?

In what ways ?

Chance plays a critical role in The Good Earth. If 0-lan had not chanced

upon the jewels in the wealthy family's house in the South, Wang Lung would

not have been able to purchase more land when they returned to their

farm. At the same time, Wang Lung believes in the virtue of hard work and

the reward of effort, which is essentially a cause-and-effect view of the

world. What does the novel ultimately say about chance versus causality ?

Writing about people of a different race or nationality can often pose

problems for authors. How would you characterize Buck's depictions of

Chinese farmers ? Does she stereotype them ? Or does she portray them

as complex individuals ? Is it possible to do something in between ?

Practices such as infanticide or taldng a concubine are very foreign and,

for many western readers, distressing. How does Buck help you understand

the complexity of these practices ? Can you think of things that we do

in our culture that would probably appear strange to people from different

countries ?

Although The Good Earth won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932 and was

instrumental in helping Buck receive the Nobel in 1938, the novel lapsed

into obscurity for many years. In what ways do you think this novel is or

is not a classic ? Why is it important (or not important) to read novels

that were prize-winning best sellers during earlier times in our history ?

The End

007

Nine Suggestions

on How To Get the Most out of This Book

『HOW TO WIN ERIENDS & INFLUENCE PEOPLE』

by Dale Carnegie

1.

If you wish to get the most out of this book,

there is one indispensable requirement, one essential

infinitely more important than any rule or technique.

Unless you have this one fundamental requisite,

a thousand rules on how to study wyll avail little.

And if you do have this cardinal endowment, then you can

achieve wonders without reading any suggestions

for getting the most out of a book.

What is this magic requirement?

Just this:

a deep, driving desire to learn, a vigorous determination

to increase your ability to deal with people.

How can you develop such an urge ?

By constantly reminding yourself how important these

principles are to you. Picture to yourself how their

mastery will aid you in leading a richer, fuller,

happier and more fulfilling life. Say to yourself over

and over: "My popularity, my happiness and sense of

worth depend to no small extent upon my skill in dealing

with people."

2.

Read each chapter rapidly at first to get a bird's-eye

view of it. You will probably be tempted then to rush on

to the next one. But don't - unless you are reading

merely for entertainment. But if you are reading because

you want to increase your skill in human relations, then

go back and reread each chapter thoroughly. In the long

run, this will mean saving time and getting results.

3.

Stop frequently in your reading to think over what

you are reading. Ask yourself just how and when you can

apply each suggestion.

4.

Read with a crayon, pencil, pen, magic marker or

highlighter in your hand. When you come across

a suggestion that you feel you can use, draw a line beside

it. If it is a four-star suggestion, then underscore every

sentence or highlight it, or mark it with "****." Marking

and underscoring a book makes it more interesting, and

far easier to review rapidly.

5.

I knew a woman who had been office manager for a large

insurance concern for fifteen years. Every month,

she read all the insurance contracts her company had

issued that month. Yes, she read many of the same

contracts over month after month, year after year.

Why ? Because experience had taught her that that was

the only way she could keep their provisions clearly in mind.

I once spent almost two years writing a book on public

speaking and yet I found I had to keep going back over

it from time to time in order to remember what I had

written in my own book. The rapidity with which we

forget is astonishing.

So, if you want to get a real, lasting benefit out of this

book, don't imagine that skimming through it once will

suffice. After reading it thoroughly, you ought to spend

a few hours reviewing it every month. Keep it on your

desk in front of you every day. Glance through it often.

Keep constantly impressing yourself with the rich

possibilities for improvement that still lie in the offing.

Remember that the use of these principles can be made

habitual only by a constant and vigorous campaign of

review and application. There is no other way.

6.

Bernard Shaw once remarked: "If you teach a man

anything, he will never learn." Shaw was right. Learning

is an active process. We learn by doing. So, if you desire

to master the principles you are studying in this book,

do something about them. Apply these rules at every

opportunity. If you don't you will forget them quickly.

Only knowledge that is used sticks in your mind.

You wiIl probably find it difficult to apply these

suggestions all the time. I know because I wrote the book,

and yet frequently I found it difficult to apply everything

I advocated. For example, when you are displeased, it is

much easier to criticize and condemn than it is to try

to understand the other person's viewpoint. It is frequently

easier to find fault than to find praise. It is more natural

to talk about what you want than to talk about what

the other person wants. And so on. So, as you read this book,

remember that you are not merely trying to acquire

information. You are attempting to form new habits.

Ah yes, you are attempting a new way of life. That will

require time and persistence and daily application.

So refer to these pages often. Regard this as a working

handbook on human relations; and whenever you are

confronted with some specific problem - such as handling

a child, winning your spouse to your way of thinking,

or satisfying an irritated customer - hesitate about

doing the natural thing, the impulsive thing. This is

usually wrong. Instead, turn to these pages and review

the paragraphs you have underscored. Then try these

new ways and watch them achieve magic for you.

7.

Offer your spouse, your child or some business

associate a dime or a dollar every time he or she catches

you violating a certain principle. Make a lively game out

of mastering these rules.

8.

The president of an important Wall Street bank

once described, in a talk before one of my classes, a

highly efficient system he used for self-improvement.

This man had little formal schooling; yet he had become

one of the most important financiers in America, and he

confessed that he owed most of his success to the

constant application of his homemade system. This is

what he does. I'll put it in his own words as accurately

as I can remember.

"For years I have kept an engagement book showing

all the appointments I had during the day. My family

never made any plans for me on Saturday night, for

the family knew that I devoted a part of each Saturday

evening to the illuminating process of self-examination

and review and appraisal. After dinner I went off by myself,

opened my engagement book, and thought over all the

interviews, discussions and meetings that had taken

place during the week. I asked myself:

" `What mistakes did I make that time?'

" 'What did I do that was right- and

in what way could I have improved my performance?'

" 'What lessons can I learn from that experience?'

"I often found that this weekly review made me very

unhappy. I was frequently astonished at my own

blunders. Of course, as the years passed, these

blunders became Iess frequent. Sometimes I was inclined

to pat myself on the back a little after one of

these sessions. This system of self-analysis, self-education,

continued year after year, did more for me than any

other one thing I have ever attempted.

"It helped me improve my ability to make decisions

and it aided me enormously in all my contacts with people.

I cannot recommend it too highly."

Why not use a similar system to check up on your

application of the principles discussed in this book ?

If you do, two things will result.

First, you will find yourself engaged in an educational

process that is both intriguing and priceless.

Second, you will find that your ability to meet and

deal with people will grow enormously.

9.

You will find at the end of this book several blank

pages on which you should record your triumphs

in the application of these principles. Be specific.

Give names, dates, results. Keeping such a record will

inspire you to greater efforts; and how fascinating

these entries will be when you chance upon them some

evening years from now.

In order to get the most out of this book:

a.

Develop a deep, driving desire to master the

principles of human relations.

b.

Read each chapter twice before going on to the next one.

c.

As you read, stop frequently to ask yourself how

you can apply each suggestion.

d.

Underscore each important idea.

e.

Review this book each month.

f.

Apply these principles at every opportunity.

Use this volume as a working handbook to help you

solve your daily problems.

g.

Make a lively game out of your learning by offering

some friend a dime or a dollar every time he or she

catches you violating one of these principles.

h.

Check up each week on the progress you are

making. Ask yourself what mistakes you have made,

what improvement, what lessons you have learned

for the future.

i.

Keep notes in the back of this book showing

how and when you have applied these principles.

The End

008

Company Philosophy:

The Way We Do Things around Here

The Will to Manage Chaptr 2

by Marvin Bower

Managing Director,McKinsey & Company,Inc

I have an abstract painting in my office that I bought

in London off the Piccadilly fence. In that open-air mart,

which operates on weekends, the artists sell their own works.

Judged by the $43 price, my painting is not great art.

But it has delightful swirls, angles, and other abstract

forms, all in bright colors. And when Mr. Eves, the artist,

told me the title - "Forces at Work" - I bought it immediately.

With a little metal plate bearing the title and the artist's

name, the painting is a constant reminder to me that any

successful organization must give continuing attention

to keeping adjusted to the forces affecting it - that is,

to the forces-at-work element of its philosophy. But before

discussing that element, let us examine the whole concept of

company philosophy as a system component and identify other

important elements of a successful philosophy.

Meaning and Elements of Company Philosophy

Over the years, I have noticed that some executives -

particularly top-management executives in the most successful

companies - frequently refer to "our philosophy." They may speak

of something that "our philosophy calls for," or of some action

taken in the business that is "not in accordance with our

philosophy." In mentioning "our philosophy," they assume that

everyone knows what "our philosophy" is.

As the term is most commonly used, it seems to stand for

the basic beliefs that people in the business are expected

to hold and be guided by - informal, unwritten guidelines'

on how people should perform and conduct themselves. Once such

a philosophy crystallizes, it becomes a powerful force indeed.

When one person tells another, "That's not the way we do things

around here," the advice had better be heeded. And when

a superior says that to a subordinate, it had better be taken

as an order.

In dealing with the concept as I find it used in practice

by leading executives, the literature on company philosophy is

neither very extensive nor very satisfactory. But one dictionary

definition of philosophy does apply: "general laws that furnish

the rational explanation of anything." In this sense, a company

philosophy evolves as a set of laws or guidelines that gradually

become established, through trial and error or through

leadership, as expected patterns of behavior.

In discussing the philosophy of International Business

Machines Corporation, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., the chairman,

says:

I firmly believe that any organization, in order to survive

and achieve success, must have a sound set of beliefs

on which it premises all its policies and actions.

Next, I believe that the most important single factor in

corporate success is faithful adherence to those beliefs... .

In other words, the basic philosophy, spirit and drive of an

organization have far more to do with its relative achievements

than do technological or economic resources, organizational

structure, innovation and timing. All these things weigh heavily

on success. But they are, I think, transcended by how strongly

the people in the organization believe in its basic precepts and

how faithfully they carry them out.'

Some typical examples of basic beliefs that serve as guidelines

to action will clarify the concept. Although such basic beliefs

inevitably vary from company to company, here are five that I find

recurring frequently in the most successful corporations:

1. Maintenance of high ethical standards in external and

internal relationships is essential to maximum success.

2. Decisions should be based on facts, objectively considered

- that I call the fact-founded, thought-through approach to

decision making.

3. The business should be kept in adjustment with the forces

at work in its environment.

4. People should be judged on the basis of their performance,

not on nationality, personality, education, or personal traits

and skills.

5. The business should be administered with a sense of com-

petitive urgency.

These five common-denominator elements - combined with

other beliefs - are informal supplements to the more formal

processes of management. A brief discussion of each will show

how useful and how powerful a company philosophy can be,

once it provides effective guidelines for "the way we do things

around here."

High Ethical Standards

In dealing with the value of high ethical standards in a

business, I don't want to belabor the obvious. But I do want to

point up a few nuances that sometimes escape even executives

of high principle.

Since the whole purpose of a system of management is to

inspire and require people to carry out company strategy by

following policies, procedures, and programs, no management

should overlook the set of built-in guidelines that every employee

with a good family background brings to the job. Since anyone

who has been well trained in Judaic-Christian ethics instinctively

acts in accordance with those principles, it is sheer

shortsightedness for any management to overlook the great practical

value of these powerful guidelines of conduct.

The business with high ethical standards has three primary

advantages over competitors whose standards are lower:

①

A business of high principle generates greater drive and

effectiveness because people know that they can do the right

thing decisively and with confidence. When there is any doubt

about what action to take, they can rely on the guidance of

ethical principles. I can think of three companies - the leaders

in their respective industries - whose inner administrative drive

emanates largely from the fact that everyone feels confident that

he can safely do the right thing immediately. And he also knows

that any action which is even slightly unprincipled will be

generally condemned.

②

A business of high principle attracts high-caliber people

more easily, thereby gaining a basic competitive and profit

edge. A high-caliber person, because he prefers to associate with

people he can trust, favors the business of principle; and he

avoids the employer whose practices are questionable. So, in taking

his first job or in changing jobs, he takes the trouble to find out.

For this reason, companies that do not adhere to high ethical

standards must actually maintain a higher level of compensation

to attract and hold people of ability. A few large companies have

to "reach" for able people with higher compensation simply

because low standards of relationships among people produce

a "jungle" atmosphere in which it is less agreeable to work.

③

A business of high principle develops better and more profitable

relations with customers, competitors, and the general public,

because it can be counted on to do the right thing at all times.

By the consistently ethical character of its actions, it builds

a favorable image. In choosing among suppliers, customers resolve

their doubts in favor of such a company. Competitors are

less likely to comment unfavorably on it. And the general public

is more likely to be open-minded toward its actions and receptive

to its advertising and other communications.

Consider the example of Avon Products, Inc., the house-to-house

cosmetics business. Since 1954 Avon's net profit has been

increasing at an average of over 19 percent a year, compounded,

and in 1963 its return on investment reached 34 percent. According

to an article in the December 1964 issue of Fortune, Avon's founder,

David H. McConnell, "was resolved to be different from the swarms

of itinerant peddlers who were at that time selling goods of

indifferent quality to housewives, and then moving on, rarely

to be seen again." The founder's son carried on his father's belief

in high principle. Citing comments by competitors and suppliers

on the company's high ethical standards, the article notes that

Avon's present chairman, John A.Ewald, its president, Wayne Hicklin,

and a top-management executive now deceased "did a great deal

to ensure that the McConnells' high ethical standards would

continue to be diffused throughout the organization as it expanded."

There should be no need to dwell on these well-recognized

values. But too often, I find, they tend to be taken for granted.

My point in mentioning them is to urge executives to actively

seek ways of making high principle a more explicit element in

their company philosophy. No one likes to declaim about his

honesty and trustworthiness; but the leaders of a company can

profitably articulate, within the organization, their determination

that everyone shall adhere to high standards of ethics. That is

the best foundation for a profit-making company philosophy and

a profitable system of management.

The End

009

Address at Gettysburg

by Abraham Lincoln

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth

on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and

dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether

that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated,

can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final

resting place for those who here gave their lives that that

nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that

we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate - we cannot

consecrate - we cannot hallow - this ground. The brave men,

living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far

above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little

note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never

forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather

to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who

fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task

remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take

increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last

full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that

these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation,

under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that

government of the people, by the people, for the people,

shall not perish from the earth.

The End

0010

Back to Basics

『IN SEARCH OF EXCELLENCE

Lessons from America's Best-Run Companies 』

by Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman, Jr.

Chapter 9

Hands-On, Value-Driven

Let us suppose that we were asked for one all-purpose bit of

advice for management, one truth that we were able to distill

from the excellent companies research. We might be tempted

to reply, "Figure out your value system. Decide what your

company stands for. What does your enterprise do that gives

everyone the most pride ? Put yourself out ten or twenty years

in the future: what would you look back on with greatest

satisfaction ?"

We call the fifth attribute of the excellent companies,

"hands-on, value-driven." We are struck by the explicit

attention they pay to values, and by the way in which their

leaders have created exciting environments through personal

attention, persistence, and direct intervention - far down the line.

In Morale, John Gardner says: "Most contemporary writers are

reluctant or embarrassed to write explicitly about values."

Our experience is that most businessmen are loathe to write about,

talk about, even take seriously value systems. To the extent that

they do consider them at all, they regard them only as vague

abstractions. As our colleagues Julien Phillips and Allan Kennedy

note, "Tough-minded managers and consultants rarely pay much

attention to the value system of an organization. Values are not

'hard' like organization structures, policies and procedures,

strategies, or budgets." Phillips and Kennedy are right

as a general rule but, fortunately, wrong - as they are the first

to say - about the excellent companies.

Thomas Watson, Jr., wrote an entire book about values.

Considering his experiences at IBM in A Business and Its Beliefs,

he began:

One may speculate at length as to the cause of the decline and

fall of a corporation. Technology, changing tastes, changing

fashions, all play a part.... No one can dispute their importance.

But I question whether they in themselves are decisive.

I believe the real difference between success and failure

in a corporation can very often be traced to the question of

how well the organization brings out the great energies and

talents of its people. What does it do to help these people find

common cause with each other ? And how can it sustain this common

cause and sense of direction through the many changes which take

place from one generation to another ?

Consider any great organization - one that has lasted over

the years - I think you will find that it owes its resiliency

not to its form of organization or administrative skills,

but to the power of what we call beliefs and the appeal

these beliefs have for its people.

This then is my thesis: I firmly believe that any organization,

in order to survive and achieve success, must have a sound set of

beliefs on which it premises all its policies and actions.